Glittering timeline with universal appeal

Kara Knack has stars in her eyes. And moons and suns and planets.

There are thousands and thousands, to paraphrase the late Carl Sagan, the great popularizer of astronomy whose enthusiasm has guided Knack’s decades-long support of the Griffith Observatory.

Celestially themed objects dangle from the ceiling of her residence in Malibu. They hang on the walls and adorn the mantelpiece, couches and chairs. They are embedded in the soil of her garden and stacked in the cupboards of her kitchen.

And more than 2,200 of them -- pieces of jewelry shaped like crescent moons, multipointed stars and radiant sunbursts -- are displayed in an undulating line along a 175-foot wall at the observatory. Known as the Cosmic Connection, the one-of-a-kind exhibit represents a timeline of the universe, all 13.7 billion years from the Big Bang to the present.

The collection, amassed over more than two decades from swap meets, junk shops, discount stores and garage sales, is a testament to one laywoman’s devotion to “public astronomy” -- the idea that reliable information about astronomy should be accessible to everyone.

A celestially themed timeline, even one made of costume jewelry, she says, allows people to reconnect with objects in the sky and perhaps inspires them to ask important questions: Why are we here? What is an individual’s place in the vast universe?

Griffith Observatory has held a special spot in Knack’s heart since her first visit in 1950, when her family traveled from Washington state to see relatives. After moving to Southern California in the early 1960s, she often went to the observatory. Knack said she would take dates there as a test, to see “whether they could be interested in something a little loftier.”

Knack, who was married to actor Pernell Roberts for 25 years, characterizes her interest in astronomy as a “guided obsession.” It is a fascination that has driven her to sniff out sheet music with heavenly themes or imagery (“Stella by Starlight,” “Moon Over Miami”), Saturn mobiles, a vintage Moonlight Mellos marshmallow tin and a night light with Betty Boop nestled in the curve of a crescent moon.

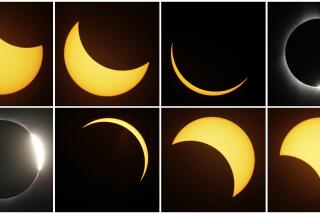

Six times she has journeyed to distant destinations (Aruba, Chile and Russia, to name a few) to see lunar or solar eclipses. Next July she plans to be on a ship in the South China Sea to observe a solar eclipse with a whopping six minutes of “totality.”

On a study tour to Mexico in the 1980s, Knack met Edwin C. Krupp, the observatory’s longtime director, who was teaching participants about ancient sites in the Yucatan peninsula and the astronomy associated with them. Impressed by her keen interest, he encouraged her to become more involved.

A member of Friends of the Observatory since 1978, she joined the support and advocacy group’s board and has served on the panel ever since. During her tenure she has been an astral ambassador, speaking often to groups about the observatory and its value to Los Angeles.

Donated to the city by Col. Griffith J. Griffith and designed by architects John C. Austin and Frederick M. Ashley, the observatory opened in 1935. In 1976, it was designated a city historic-cultural monument.

Over the years, crowds loved the place almost to death. Holes were worn in the linoleum floors. The roof leaked. The original 1930s air conditioner was still in place.

In early 2002, the observatory closed for a renovation and expansion. Nearly five years later, in November 2006, it reopened after a $93-million makeover.

Soon after the museum went dark, Knack and Krupp began suggesting ideas for how to use her jewelry collection, but a task force of invited astronomers, science writers, academics and curators rejected them. The panel contended that exhibiting arguably kitschy items from popular culture might appear shallow and, to say the least, unscientific.

In 2003, Krupp prevailed, insisting that “a ribbon of jewelry will serve as a timeline of the universe.” Just days before the Galactic Gala on Oct. 29, 2006, that marked the reopening, Knack unrolled a 165-foot-long piece of paper in her driveway. She drew a line that she said looked like a giant string snapped like a whip.

At the Los Angeles jewelry mart, she bought connectors, pins, nails and needle-nosed pliers. She enlisted 18 volunteers who stationed the jewelry along a display board, earring by bracelet by necklace by pin, with Knack organizing the pieces to appear “random and chaotic.” Having worn almost every piece to one occasion or another, she knew them well.

Although the jewelry was in place in time for the opening, it took until last March for the museum to complete and hang the interpretive panels that describe momentous events in the universe’s history.

Because the timeline is just outside Krupp’s office, he often strolls by. Invariably, he said, people are congregated there, reading the illustrated panels.

“It’s a very digestible universe for people,” Krupp said. “They’re drawn by this unexpected way of displaying the march of cosmic time.”

Many are captivated by individual pieces, such as the luminous moonstone earrings, a Scandinavian pin featuring a kissing sun and moon, the star-shaped copper earrings from Germany, the necklace with a ceramic astronaut and star (donated by a teacher whose students had crafted it for her), the “shooting star” hair combs made to commemorate Halley’s comet or the all-black Victorian mourning jewelry.

“Everywhere I’ve been, I’ve found celestiana,” Knack said.

Her favorite is a lightweight, multistrand necklace worn by a board colleague’s mother when she sang “Carmen” in Denver at the turn of the last century.

One recent afternoon, Nathan Duft, 10, visiting from Novato, Calif., paused on his way to the observatory’s cafe to study the timeline. “I think it’s really awesome,” he said.

Zachary Lerman, 11, of West Los Angeles described the pins and other items as “so sparkly they actually look like stars.”

Such words are like stardust to Knack.

“Col. Griffith thought observation would lift people from the trenches of ignorance,” Knack said. “That’s what happened to me.”

Groves is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.