She needs piping hot oil

They’re three hours into the contest, cooking hard, when team captain Marissa Gerlach peers into the deep fryer and glimpses potential doom. Not this, she thinks. Not now.

She’s tried to anticipate every calamity. She’s practiced sick, juggled work, labored for hours with her fellow aspiring chefs in their Costa Mesa school’s cramped kitchen.

In the last year, Gerlach has led the five-student “hot food” team at Orange Coast College to victory over rivals across California and the western United States, repeatedly shaming more expensive, better- equipped schools.

Now, working on little sleep and an empty stomach -- she skipped breakfast to search for a missing pan -- the 22-year-old Laguna Niguel student is in the thick of the Super Bowl of college cooking, the American Culinary Federation’s national championships.

She’s running behind, trying not to panic, her teammates whirling around her in a cacophony of knives, whisks and blenders. It took her longer than expected to cut the pork, which set her behind in filleting the fish -- which means the hundred other things she must do got pushed back too.

She graduates this year, so it’s the last hour of the last contest in her two-year career as a student cook, and no one aches worse for the first-place trophy. She imagines holding it on the plane ride home.

She’s responsible for her team’s entree, a smoked pork tenderloin with sun-dried tomato sausage, apricot compote, glazed carrots and haricots verts, French string beans.

The team is aiming for haute cuisine while evoking memories of childhood summers. “I want white trash,” their coach told them. “I want what I grew up with.”

Which is why, accompanying her elegant entree, Gerlach will deposit the humblest mainstay of American cooking: a scoop of macaroni swimming in Velveeta cheese and cream, which she will deep-fry in a crust of panko, a Japanese bread crumb.

This is the team’s masterstroke, consistently praised by the test audiences the team served to raise donations to pay its way to Orlando. A witty hybrid of low and high culinary culture, it’s a crispy little cannonball designed to pierce the judges’ jaded hearts and make them wistful for their vanished childhoods.

With just minutes to spare before plate-up, Gerlach hauls the scoops, breaded and chilled, to the deep fryer.

She looks inside, only to see that the oil isn’t hot.

The oil isn’t hot because the fryer isn’t on.

The fryer isn’t on because it isn’t plugged in.

It was plugged in, at the start. Somehow the cord popped loose.

Which leaves Gerlach facing an excruciating choice: Find another way to cook the breaded scoops and send the entrees out late . . . or send them out on time, denuded of their secret weapon.

She learned to cook as a teenager, baking Christmas cookies with her mother. Soon, she and her mom, who is of Armenian descent, were in the kitchen making fabulous meals of lamb kebabs and cucumber-and-yogurt salad.

Gerlach learned to make rice pilaf with vermicelli browned in butter, which generated a singular, toasty smell she now finds inseparable from memories of home. Now, she teaches her mother, who is a little surprised by her daughter’s perfectionism.

“She just went way over me,” Sharon Gerlach says. “School was never her favorite thing, and she found something she absolutely loves.”

For the last five years Marissa Gerlach has been holding her own in one testosterone-drenched restaurant after another, often as the cooking crew’s only woman.

Most recently, while pursuing her degree at Orange Coast, she has cooked at an upscale Laguna Beach resort. A guy who didn’t like taking orders from her put salmon in her coffee; another smeared her face with fish slime. Once, she went to the bathroom and cried. Just once.

“There are names they call me at work,” Gerlach said. “They call me bossy. I am bossy, but in the kitchen, a lot of people are,” she says. “For me, I’m into fine dining, so it is about perfection.”

She’s been sick nearly a dozen times since preparation for the contest began a year ago, worn down between shifts at the restaurant and twice-a-week practices. She has a callus in the palm of her knife hand, nicks on her fingers and fading burn marks on her wrists.

She still lives in Laguna Niguel with her mom, who for months has watched her come home from work around midnight, after long shifts, only to cook for whomever was still awake. Then she’d stay up to make chicken stocks for the competition, falling asleep with the timer on.

“My mom doesn’t even understand it, and I explain it to her every day,” Gerlach says. “She doesn’t realize that if you lose one pin bone out of that fish and a judge catches it, you’re knocked down two to four points.”

When this contest is over, she will head to Sonoma County to cook at a top-tier restaurant in the heart of wine country. It’s a breakthrough job that will advance her goal of becoming an executive chef, although her boyfriend, a waiter, won’t be going with her.

“I can’t just stop because I’m dating,” she says.

Here at the finals, on a morning in July, each team has exactly four hours to turn out 24 portions of a four-course meal of its own creation. The winners get an edge in the increasingly competitive kitchens of America, now flooded by culinary school graduates besotted by the mystique of the celebrity chef.

Despite the coast-to-coast proliferation of private culinary academies, the four teams that have made it to the finals are from public schools, three of them from community colleges. At Orange Coast, a two-year culinary degree runs about $2,500, about 20 times less than at some private academies.

Gerlach’s team and its three rivals are ranged side by side in improvised kitchens at the Orlando Marriott convention hall.

The clock starts at 8:45 a.m. Gerlach begins by cutting her six pork tenderloins. Because she’s the best hand at fish, she must also fillet the Arctic char -- a close relative of salmon -- for the appetizer man, 21-year-old Brodie Curtis of Newport Beach, who will garnish it with mesh-cut chips, summer slaw and sweet corn sauce.

Once a hyperactive kid with attention-deficit disorder, Curtis found comfort in the tactile demands and nonstop pace of the kitchen.

Gerlach needs her sun-dried tomatoes diced but doesn’t have time to clean her cutting board. So she dispatches the team alternate, 24-year-old Chad Urata of Irvine, to enlist the salad man, Conrad Malaya of Cypress, who turns 26 today and is singing “Happy Birthday” to himself to break the tension.

He’s making cracker strips that will encircle a disk of citrus-drenched watermelon. A banquet cook at Disneyland, Malaya claims not to care about winning, but he jumped out of bed last night to scribble down a last-minute list using the light of his cellphone: Peel carrots, cut carrots, peel watermelon.

Malaya is recently married, and his wife -- who picked out the wedding flowers alone because he had practice -- can’t wait for this contest to be over.

Across from Malaya, the dessert man, 23-year-old Brent Omeste of Orange, is baking whole-wheat crackers into a s’mores-style chocolate pate. This will accompany a slice of strawberry shortcake and an inverted cone of vanilla mascarpone.

Omeste left a girlfriend who couldn’t grasp the importance of spending every spare moment in his school’s kitchen, agonizing over a marshmallow that refused to stand up. “She didn’t get it,” he says.

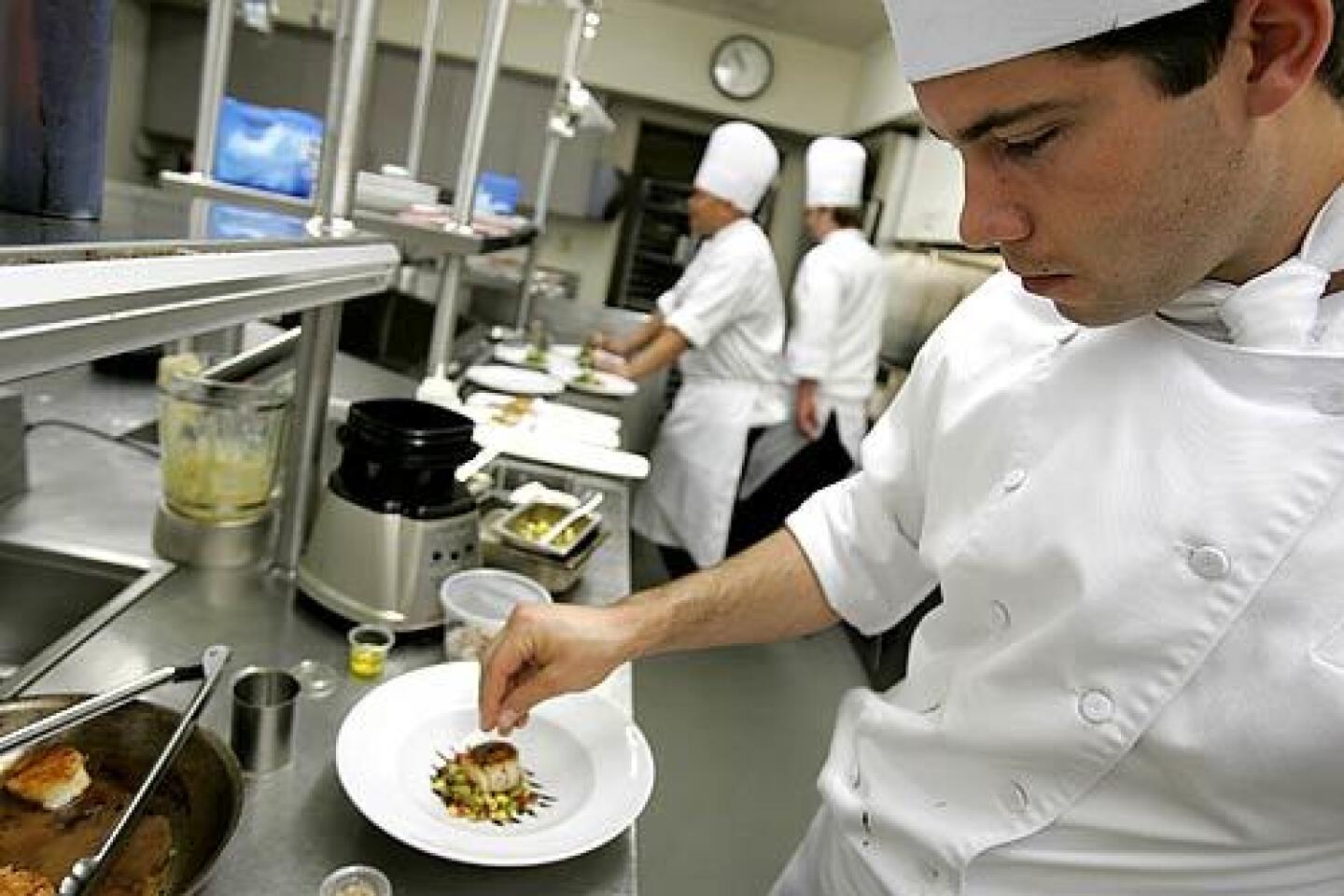

The students thread around each other, each member anticipating the moves of the others, dozens of individual tasks timed to minutes and seconds.

An hour into the contest, several things have gone wrong.

Omeste burned his lemon zest on the unfamiliar electric stove-top. Malaya sliced his watermelon open, only to find the flesh cracking, forcing him to scrap portions. Gerlach took 45 minutes to cut her pork, 15 minutes longer than she allotted. But no disasters yet.

Since the contest began in 1992, Orange Coast’s cooking teams have fared well -- dominating the state in recent years and winning the nationals two years ago -- but last year’s team flopped. The cooks didn’t get along.

This season, heading into the state competition in November, expectations were so low that team members had to buy their own $40 chef coats.

Among the teams they faced, one looked indomitable: Professional Culinary Institute, a private Campbell, Calif., school that charges $23,000 for a six-month program and won the nationals last year.

To its surprise, Orange Coast inched to victory when its rival lost points for late desserts. Then in April, at the Western regional championships in Idaho, Gerlach dazzled judges with an entree of classical French cooking involving poached chicken with beef tongue.

For the finals, the team had to haul nearly 500 pounds of equipment by plane from California. There were last-minute emergencies and near-calamities. The dessert ingredients didn’t make the flight and had to be replaced. The cord for the deep fryer was missing, so Urata ran to Target for a new $60 machine. They plan to use the cord, then return the machine.

“We kind of scrape by every year to do this,” says Coach Jeremy Peters.

Here comes crunch time. At 11:45 a.m., 15 minutes before plate-up, Malaya is whipping up an emergency bath of aioli -- a kind of garlic mayonnaise sauce for the appetizer -- because the first batch failed to emulsify.

Omeste is waving a propane torch over his s’mores pate, browning the marshmallow. He lost five ice cream cones and had to make an unexpected second tray, so he’s behind and hustling, sweating through his paper hat, which keeps sliding off his head.

Just before noon, Gerlach takes her macaroni and cheese -- packed neatly into plastic molds and chilled -- and pops each scoop one by one into the Japanese breadcrumbs, rolling them.

Malaya: “How long till we plate?”

Curtis: “Three minutes!”

At 12:05 p.m., the appetizer plates begin going out. They are beautiful. Sixteen minutes later, the finished salads start hitting the counter. Beautiful.

Meanwhile, Gerlach hauls the mac and cheese balls to the deep fryer and discovers the loose cord. There is no time to get the oil hot enough.

Now comes the impossible choice.

Should they try somehow to get the mac and cheese balls on the plate -- maybe throw them in a pot or saute pan -- and risk sending their dishes out late, which is sure to cost them points?

Or should they aim for a timely finish, sending their plates off punctually but bereft of their signature flourish, their crunchy, Velveeta-creamy flash of memory-evoking brilliance, their mystical portal to vanished childhood summers?

Their fates perched precariously on those crumby, cold spheres, they just keep plating. Nobody speaks up. And that is how, tacitly, the decision is made to send their entree into the world maimed.

With seconds to spare, the team’s final desserts clank onto the counter. They beat the clock. The team is jubilant.

Coach Peters curses. He stalks away. He returns to commiserate about the mac and cheese with another team coach, Keith Noriega, who says ruefully, “That’s our starch.”

“I would have stuck that on a saute pan and thrown it on there,” Peters says. “She had it ready.”

Afterward, Urata takes the blame. He should have made sure the deep fryer was plugged in. Gerlach says no, the entree was her dish, and she was responsible. She is glum.

“My thought is, I’d rather not have it if it’s not gonna turn out right,” she says. She reconsiders. “I should’ve thrown it in a pot.”

Soon, the judges pull the team behind a curtain to critique its food. They say the fish should not have been obscured by the slaw, that the shortcake wasn’t flavorful, that pork tenderloin is a bad choice for a competition. Several mention the missing mac and cheese.

“Yes, chef,” the young cooks say stoically, as each judge takes his turn.

“All in all,” one judge sums it up, smiling, “a good job.”

That night, Gerlach styles her hair in a bob, puts on an elegant blue halter top embroidered with flowers and slips into ivory-colored high heels.

She joins her team -- along with hundreds of other attendees of the American Culinary Federation’s four-day convention -- in a hotel ballroom.

The Orange Coast cooks share a table. The federation president stands at the microphone to announce the winners.

Gerlach grabs the hand of Curtis, the teammate next to her, and squeezes.

Fourth place: Oakland Community College in Michigan, which failed to master its entree of roasted rack of lamb and turned out a peach-and-nectarine dessert deemed too sweet.

She looks at her teammates and thinks: At least we’re not last.

Third place: The State University of New York at Delhi, which turned out a nice veal rib-eye but was told its mixed-green salad was too easy for this level of competition.

She thinks: Did the other teams make blunders worse than ours?

Beside her, Curtis says: “I’d be totally happy with second.”

Beside him, Omeste says, “Breathe.”

Beside him, Malaya -- who claims not to care about winning but is now grimacing at the ceiling -- says, “It’s getting tough.”

Here comes the news. They’re ready to scream.

Second place: Orange Coast College.

No one smiles. They go to the stage for their medals and walk away solemnly.

The winner is Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College in North Carolina, which aced its entree of chicken with smoked beef tongue, even though a judge thought the berry compote on its lemon-cookie dessert could have been tangier.

The judges do not explain how they totaled up the final points. This may be a mercy.

“I don’t even want to know,” Omeste says.

Late that night, Gerlach calls her mother, who can hear the devastation in her voice. Sharon Gerlach tries to tell her it’s just a contest, but it’s small consolation. She knows her daughter. “She puts her heart into it,” she says. “Way too much.”

When Gerlach arrives back in California, she must start packing to begin her job at the Sonoma County restaurant.

For her goodbye dinner, her extended family comes to the house, four generations worth. She works on holidays and misses most family gatherings, so this day is a rare thing.

She and her mother cook through the afternoon, drinking wine and laughing.

They make cucumber-and-yogurt salad, plus another big salad with vinegar and oil, red onion and tomatoes. They make flatbread with meat and bell peppers, kebabs of lamb and chicken marinated in garlic and onions. They make rice pilaf, and her home fills with the singular smell of vermicelli browning in melted butter. Then they bring the dishes out to the waiting family.

christopher.goffard@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.