From the Archives: Releasing Inmates Early Has a Costly Human Toll

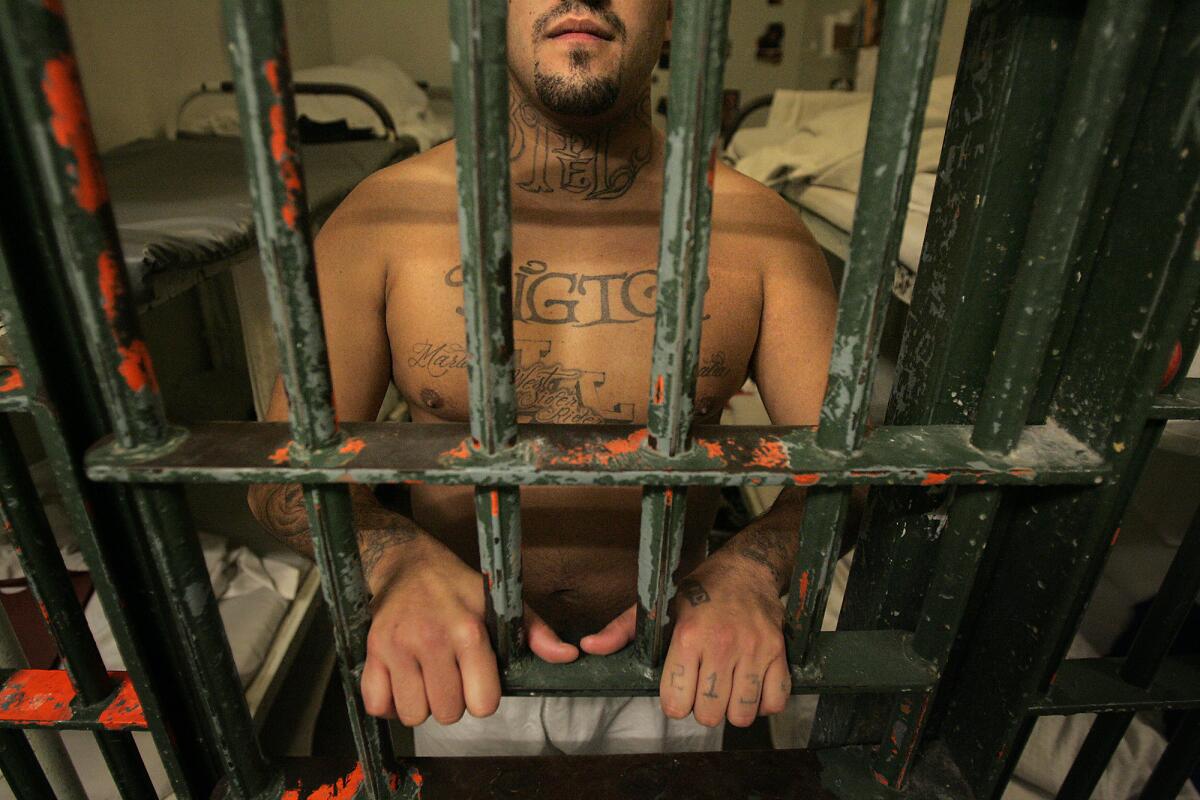

Mario Moreno should still have been behind bars the night he climbed into the passenger seat of a stolen car with two fellow gang members.

He was carrying a rifle, some cartridges and, in his jacket pocket, a bag of marijuana. “Let’s go do this,” the car’s driver recalled Moreno saying as they headed into the turf of a rival black gang.

They drove by a liquor store at 89th Street and Central Avenue in South Los Angeles. Two older black men were standing outside.

Moreno, 18, aimed his weapon out the driver’s-side window and fired. One bullet killed Darrell Dennard, 53, a grandfather who slept in an alley behind a nearby fish market and got by doing odd jobs. He had just bought a lottery ticket. It was about 9 p.m. on Oct. 11, 2004.

If not for a chronic shortage of jail beds in Los Angeles County, Dennard’s killer would have been in jail four more months. Moreno had been convicted of possessing a sawed-off shotgun -- a felony. A probation officer called him a “danger to the community,” and a judge sentenced him to a year in jail, the county maximum. Six days later he was released into a work program. Since his arrest, he had served a total of 53 days.

Moreno joined more than 150,000 county inmates who have been released during the last four years after serving fractions of their sentences. Thousands, like Moreno, committed violent crimes when they would otherwise have been locked up, even with time off for good behavior.

The large-scale releases started in mid-2002, when Sheriff Lee Baca had to make major budget cuts. Unwilling to lay off patrol officers, he chose to close jails.

As a result, nearly everyone now sentenced to 90 days or less is let go immediately. Many others leave after serving no more than 10% of their time, making Los Angeles County Jail sentences among the weakest in the nation.

A Los Angeles Times investigation of early releases since Baca’s jail closures began found:

* Nearly 16,000 inmates -- more than 10% of those released early -- were rearrested and charged with new crimes while they were supposed to be incarcerated.

* Nearly 2,000 of those rearrested were released early a second time, only to be arrested again while they should have been behind bars. Hundreds of those people cycled through jail three or more times. One example of the revolving door: A 55-year-old woman was released early in 2002 on an assault charge, only to be rearrested three days later on suspicion of another assault. Over the next three years, she was released early 15 times and rearrested 19 times when she was supposed to be locked up.

* Sixteen men, including Moreno, were charged with murders committed while they should have been in jail. Nine are awaiting trial; seven have been convicted in the homicides.

* More than a fourth of those rearrested were charged with violent or life-endangering crimes, including 518 robberies, 215 sex offenses, 641 weapons violations, 635 drunk-driving incidents, 1,443 assaults and 20 kidnappings.

Many of these inmates probably would have committed new offenses even if they had served full sentences. But the early releases have given career criminals more time on the streets to commit additional crimes, endangering the public.

Juvenal Valencia, 21, was convicted of assault with a deadly weapon, released early and then cycled in and out of jail twice more after early releases. Prosecutors have now charged him with first-degree murder in a drive-by shooting that left one man dead and five others wounded. He has pleaded not guilty. At the time of the killing, Valencia had two months left to serve for a probation violation.

In recent years, sheriff’s clerks have routinely disregarded sentences handed down by judges. In some cases, inmates are freed despite instructions from a judge that they must serve their full sentences.

“That puts us all in peril,” said Los Angeles City Atty. Rocky Delgadillo. “I think criminals have learned from this that there is a way to beat the system.... For many, a few days in jail has become just a cost of doing business.”

Los Angeles Police Chief William J. Bratton, who led the Boston and New York police departments before taking over in Los Angeles in late 2002, said the situation has frustrated officers on the street and made policing harder.

“It’s an amazing system. I’ve never seen anything like it,” he said. “The police, prosecutors and judges -- sometimes even a jury -- have made decisions, and you have the ability to arbitrarily undo all of that.”

In recent interviews, Baca defended his decision to release inmates early as a “last resort,” saying he had little choice but to shut down jail facilities when he had to cut millions of dollars from his budget.

At the time, Baca warned that crime would increase if he weren’t given more money. “In a public safety fashion, the net will be cut and the floodgate will be open to more crime,” Baca told county supervisors at a 2002 board meeting to which he had brought a thousand supporters.

Now, he says, the public is paying the consequences.

“I knew that there are people in our county jails that are so unstable that even if they’re only in there for a minor crime, they’re capable of committing a bigger crime,” he said. “You just can’t predict who that person is going to be, specifically.”

A bond measure of up to $500 million to fund improvements to -- and expansion of -- the jail system is being considered for the November ballot.

But even if the extra millions come through, sheriff’s officials say they won’t be enough to fix long-neglected jails.

The sheriff has little control over who comes into his jails. In recent years, bookings have steadily increased, partly the result of a jump in arrests by Los Angeles police. And more than a thousand jail beds are regularly taken up by prisoners awaiting transfer to state facilities, a process that takes weeks.

Today, the county has about 19,000 jail beds in use. Baca says he would need at least 30,000 -- and additional deputies -- to end early release.

‘A Truly Innocent Victim’

Darrell Dennard was always better at taking care of others than himself. When his grandmother was gravely ill, he stayed with her day and night, bathing and feeding her until she died. But he chose to make his home on the streets of South Los Angeles where he’d grown up, preferring his tidy bedroll to numerous offers of a warm bed.

A little over a week before Moreno killed him, Dennard’s mother, Gladys Derrick, visited her son in the alley behind the fish market. She brought travel-size lotions and shampoos and a basket of “all kinds of things he didn’t have to cook.” He was “always good company,” she said.

“It’s not very often that you have a truly innocent victim,” said LAPD Det. John Skaggs, who investigated the killing. “This of course is that case.”

Half a dozen members of Dennard’s family were in the Compton courthouse on March 27 to see Moreno sentenced to state prison for voluntary manslaughter, a plea prosecutors said they offered because witnesses wouldn’t testify.

Dennard’s sister wore a T-shirt printed with her brother’s smiling image and the dates marking his life: 9/26/51-10/11/04.

Moreno, a member of one of the county’s most notorious gangs, Florencia 13, smiled at his family when he entered the courtroom. A girlfriend powdered her nose. His mother, her hair tied back in two long braids, read a Bible.

Dennard’s brother, Howard McZeal, addressed the court.

“I’d like to know why my brother isn’t here,” McZeal said, his voice cracking. “What did he do to you?”

Moreno stared straight ahead.

Until speaking to a Times reporter shortly before the sentencing, Dennard’s family had no idea that his killer had gotten out of jail with months still to serve.

“A gang member arrested with a sawed-off shotgun? That [jail time] was a camping trip to him, a business junket,” McZeal said later.

“If that man had still been in jail, Darrell would still be alive.”

A Crush of Inmates

A generation ago, no one in Los Angeles got out of jail early.

When beds were full, inmates were housed in hallways, common rooms, the pews of the jail’s chapel and anywhere floor space was available. In the summer of 1983, with the building filled to twice its capacity, hundreds of inmates were given four blankets each and slept under the stars on the roof of Men’s Central Jail.

By then a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of inmates by the American Civil Liberties Union was making its way through the court system. A federal court found the overcrowding to be cruel and unusual punishment and ordered the county to stop overloading its jails. At the time, more than 22,000 inmates were being housed in space meant for half as many. County officials, under a federal consent decree, agreed to open new facilities.

In 1988, the judge allowed the county to institute what was to be a temporary solution to the overcrowding: early release.

The number of early releases ebbed and flowed, but by the late 1990s it had slowed to a trickle. Then, in mid-2002, Baca faced two years of budget shortfalls, forcing $167 million in cuts.

County supervisors said they had little choice but to rein in spending. During that time, state and county governments were reeling from losses in tax revenue caused by fallout from the dot-com bust. Other county departments were also hit hard.

“We did what we could to maintain” the sheriff’s funding, said Supervisor Yvonne Brathwaite Burke.

Baca was already dealing with a jail system that had lost 5,000 beds in a decade, mostly from earthquake damage. In little more than a year, he closed three more jails and shut down parts of four others, reducing the number of inmates by another 5,000.

The cuts saved more than $50 million. But they also guaranteed a new wave of early releases.

Baca’s critics point to “nonessential” pet projects, like rehabilitation programs in the jail, that could have been cut to keep inmates in jail longer.

“That’s nice, but that’s not our job. Our job is custody,” said Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Sgt. Paul Jernigan, who works in Men’s Central and is one of four candidates running against Baca in the June 6 election.

But the sheriff said these programs amounted to a fraction of the money he needed to save. With cuts down to the bone, he said he faced laying off deputies or closing the jails.

“If you were to ask the community, ‘I’ll take away five police cars in your neighborhoods or I’ll do early release,’ ” they’ll say, ‘Don’t take away the five radio cars. Now manage your jail the best way you can.’ So I did,” he said.

In the last two years, Baca’s department has benefited from an increase in county revenue from property taxes, fueled by a surging real estate market. More than half the beds closed since 2002 have been reopened. The department has the funds, but not the staff, to reopen the remaining 2,500 beds.

And there is still the problem of aging and outdated facilities at a time of growing pressure to reduce violence among inmates and relieve overcrowding that has continued despite the large-scale early releases.

In Men’s Central, cells designed for three inmates are filled with six. Last week, U.S. District Judge Dean D. Pregerson described the practice as “simply not consistent with basic values,” noting that inmates did not even have the space to stand up and take a step or two. Pregerson, who oversees the still-open civil rights case on jail conditions, said the situation “should not be permitted to exist in the future.”

A Balancing Act

Last year, 32 of California’s 58 counties -- including Orange, San Diego, San Bernardino and Riverside -- released inmates before they had completed their jail sentences.

Los Angeles County, with the largest jail system in the nation, has led the way. In the 3 1/2 years before Baca closed jails, about 10,000 inmates were let out prematurely. In the 3 1/2 years that followed, almost 150,000 were released three or more days early.

With fewer beds, the sheriff has also had to loosen standards on who qualifies for early release.

“By lowering that criteria, you’re qualifying more hardened criminals,” said Sheriff’s Capt. Bill Bengtson.

Until The Times asked for data, sheriff’s officials had not tracked how often inmates were rearrested when they would otherwise have been behind bars. In February, the officials hastily conducted an analysis of rearrests before giving the newspaper data on more than 2 million bookings into the jail since 1999.

The Sheriff’s Department analysis, which looked at the seven years of data as a whole, concluded that inmates released early were no more likely to re-offend than those who were not.

But The Times found distinct differences when it compared the years before the jail closures with those after. As fewer served full terms, rearrests within 90 days of release increased for all inmates. Those released early after the policy change were more likely to be rearrested within 90 days than inmates who served their full jail time.

The Times analysis also showed that although the number of inmates released early increased 15-fold after mid-2002, arrests of people with time left on their sentences rose about 60-fold, from 266 to 15,775. Rearrests for violent and life-threatening crimes soared from 74 before the jail closures to more than 4,000 since.

Among the perpetrators: Hector Aguilar, who left jail Sept. 1, 2004, with three months left on his sentence for domestic violence. Four days later, he opened fire with an AK-47 assault rifle on a sheriff’s patrol car, missing two deputies inside. He pleaded guilty to assault with a deadly weapon and was sentenced to 43 years in state prison.

In deciding which inmates deserve the most time, sheriff’s officials try to balance overcrowding against the need to keep dangerous criminals locked up.

The inmate pool for early release is limited to about 10% of the jail population -- convicts sentenced by judges to less than a year. The remaining inmates are awaiting trial or transfer to state prison for longer sentences, or are incarcerated for parole violations under a contract with the state.

Since late 2004, a small number of beds -- now about 75 -- has been reserved for inmates sentenced to jail who have been identified by the LAPD as chronic, dangerous offenders. They do their full time. Occasionally, inmates arrested for specific crimes in specific areas are also kept longer. In recent months, for example, sheriff’s deputies have cracked down on prostitution in parts of South Los Angeles and Compton. Current guidelines say prostitutes arrested there “shall serve 100% of their sentence, and shall NOT be released [early].”

Guidelines issued by the sheriff spell out which inmates in the 10% pool qualify for early release: Those in jail for manslaughter, sex offenses and child abuse, along with violators of gang injunctions, do all of their time. For nearly all other convictions, inmates serve a fraction of their sentences. Women, who are housed in separate, less crowded facilities, usually do no more than 25%. Men serve no more than 10%.

If jailers had the room, a typical inmate given a year in jail would spend about 243 days behind bars after discounts for good behavior and work. As it is now, an inmate eligible for a 10% release would serve just 24 days.

“That’s a disaster,” said Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley. “Obviously, if they aren’t in, they can be out committing crimes.”

‘Get Them Out’

Most of the time, the decision to free an inmate comes down to a simple mathematical calculation. A first-time offender is treated the same as a career criminal. There is no penalty for prisoners who have been rearrested while on early release. Prior convictions for violent crimes are not taken into consideration.

Each day the decision of who goes home early is made in cramped cubicles at the county’s Inmate Reception Center. Sheriff’s clerks work eight-hour shifts, reviewing inmate files to identify those who meet the sheriff’s criteria for early release.

On a recent morning, Pamela Broom’s desk was stacked with a dozen or so manila envelopes, filled with paperwork on candidates for early release.

Broom pulled the envelope of Rosa Louise Degraw. A blond, plump face glared from a booking photo. The jail’s computer showed that Degraw was serving a 180-day jail sentence for battery and vandalism. With time off for good behavior, she was supposed to serve about four months.

Degraw’s sentencing documents contained an explicit directive from the judge: “No early release.”

Instead, 33 days after she was booked, Degraw was eligible to go.

“The sheriff says, ‘It doesn’t mean anything. I’ve got to get them out of my jails,’ ” said Broom’s supervisor, Greg Sivard.

Degraw had landed in jail after repeatedly violating her probation requirements following a conviction for battery and vandalism. Among her battery victims: her mother.

Broom said she has little time to reflect on whom she is releasing.

“I’d be in a mental ward,” said Broom, who finds anywhere from two to 40 inmates each day to release early. “You follow the criteria. You get paid to do your job, not have opinions.”

In red ink on the envelope, she marked Degraw free to go.

Two and half hours later, Degraw, 23, pushed her way through a metal jail door onto Bauchet Street in downtown Los Angeles.

She was angry she’d served as much time as she had. Dressed in the same white tank top and blue jeans she had come to jail in, Degraw said she believed she’d serve only 10% of her sentence. Still, she said, the extra time made her want to avoid coming back.

“The longer you make them stay in there and think about it, the chances are less that they’ll get out and do something else,” she said.

Degraw said she planned to reunite with her 4-year-old son and try again to earn her high school equivalency degree. For the immediate future, she had other plans: “I’m going to drink me a bottle of Southern Comfort today.”

Freed Without a Review

In 2003, Baca tried to reassure the public about his early-release program.

“It should be clear to those who are listening that we are going to put them in programs and ankle bracelet monitoring,” Baca said, appearing on KCET-TV Channel 28’s “Life and Times” in April 2003. “They’re not just walking out the door with no obligations.”

For a few months in 2003, jailers reviewed criminal histories before approving early release. Then they abandoned the effort, saying it was too time-consuming. Since then, inmates have been freed without anyone looking at their full criminal past. Many had long arrest records.

More than 4,400 released early after the jail cuts had been prosecuted for assaults with deadly weapons or seriously injuring people. Today, the department has far fewer inmates on electronic monitoring and other types of supervision than it did in 2001.

Elsewhere, jail officials do more to determine which inmates are likely to endanger public safety. In Portland, Ore., the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Department examines the criminal records of inmates so convicts with violent pasts do more time regardless of their most recent offenses.

After questions from The Times, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Chief Marc Klugman said the department would consider once again looking at criminal histories and other factors to determine whether an early release was appropriate.

Baca said judges and prosecutors also bear some responsibility. He said they are well aware that he is releasing inmates early, yet continue to agree to plea bargains that send dangerous offenders to jail instead of prison.

Creative Sentencing

In 2002, Vincent Jeffery led sheriff’s deputies on a chase through the streets of South L.A., hitting speeds of more than 80 mph, running eight red lights and crashing into a motorist. A deputy said Jeffery, who had a 20-year record and 10 aliases, pulled a gun on him when he tried to make a routine traffic stop.

On Sept. 30, 2002, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge James R. Brandlin sentenced Jeffery, 36, to two years in County Jail. Eight months later, he was back on the street.

Brandlin, who had called Jeffery a “tremendous risk to public safety,” demanded answers in a letter to Baca.

The sheriff had his aides look into the case. Jeffery, Baca wrote back to the judge, had been released properly by sheriff’s officials struggling to keep the jail population down.

“While this may not meet with your approval,” Baca said, “I sincerely hope that it allays any concerns you have that Mr. Jeffery was incorrectly released.” Brandlin declined to comment for this story.

As more and more inmates realized that there was little risk of serving full sentences, fewer accepted deals to serve their time under house arrest or through community service. And as alternative sentences dwindled, more pressure was put on the jails.

“You tell a guy now, ‘Hey, 30 days Caltrans,’ ” Cooley said. “He says ... ‘You know what, I don’t need all that jazz. Give me my time.’ ”

Cooley said frustrated prosecutors and judges seek creative ways to “beat the sheriff’s sentencing system.”

Here’s how prosecutors and one judge made sure that a defendant served his time.

In September, sheriff’s deputies caught Steven Torres strolling through his Compton neighborhood carrying a large glass bong and a small pipe containing drug residue. He was on probation for previously carrying a concealed weapon. A search of his home turned up another handgun -- a serious violation.

His probation officer wrote that Torres should “spend a suitable amount of time in local custody” to show him that “criminal behavior will not be tolerated.”

At a November hearing, where Torres pleaded no contest, Superior Court Judge Xenophon F. Lang Jr. told him he would “serve 90 actual days in the County Jail” and ordered him to surrender to the jail in January to await sentencing.

In March, at Torres’ sentencing hearing, Lang smiled at the bulky defendant before him in handcuffs. The judge reminded Torres of the 90-day sentence he had proposed earlier.

“It appears he has done that,” Lang said with a chuckle, ordering Torres released on probation.

Fatal Consequences

On Oct. 30, 2003, Jose Rafael Garcia stopped his motorcycle at a red light in East Los Angeles. It was about 9:30 p.m. The 31-year-old father of two had finished a day of construction work and was idling at 3rd Street and Arizona Avenue.

Randy Morones, 33, had been rousted from a jail bed about 2 a.m. It was his 11th day in jail on a drug conviction. He had been sentenced to six months.

In 1999 and again in 2000, he had been convicted of beating a girlfriend and sent to state prison. His latest offense marked his seventh stay in County Jail in four years. Since 1989, he had been convicted of drunk driving four times.

None of this mattered when Morones again came up for early release. Because he had served 10% of his jail time, he was free to go.

Morones left the downtown jail complex about 8:30 a.m. By evening, he was drinking beer at a friend’s house. Then he climbed behind the wheel of his 18-foot motor home and headed to his parents’ Pico Rivera home, speeding along 3rd Street.

Witnesses said he didn’t even hit the brakes as he approached the red light at Arizona. He slammed into Garcia, throwing him more than 130 feet and killing him. Morones ran from the crash site, but witnesses caught and held him until deputies arrived.

In September 2004, a jury found Morones guilty of second-degree murder and gross vehicular manslaughter while drunk. At his sentencing, Morones apologized to Garcia’s family: “I wish the Lord took my life instead of an innocent man.”

He was sentenced to 20 years to life in state prison.

Galdino Garcia wept when he spoke recently of the crash and his memories of his brother.

A Mexican immigrant, Jose played guitar in Latin rock bands. He spent time riding his motorcycle in the San Gabriel Mountains, telling his family that the rides made him feel like he was “caressed by God.”

Galdino Garcia said he blames the justice system as well as Morones.

“I believe in the law, but that was one of my questions: Why did they let him out early?” Galdino said. “They never answered me that question.”

Times researcher Maloy Moore and staff writers Robin Fields and Stuart Pfeifer contributed to this report. Data analysis by Doug Smith and Sandra Poindexter.

*

Recidivism

After early releases mushroomed in mid-2002, all county inmates were more likely to be rearrested within 90 days after being released. But the rearrest rate almost tripled for those let out early.

Before jail closures After jail closures Full term 13.1% 18.5% Early release 7.7% 20.6%

Does not include inmates released after Sept. 30, 2005

Source: Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Data analysis by Sandra Poindexter

*

Free to re-offend

From July 2002 to December 2005, the number of inmates who should have been in jail who were:

Released early 148,229 Rearrested 15,775 Charged with assault 1,443 Charged with robbery 518 Charged with a sex offense 215 Charged with murder 16

Sources: L.A. County Sheriff’s Department; L.A. Superior Court

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.