Real Estate Deals Pay Off for Insiders

The financing was set and the plans were drawn, dotted yellow lines showing just where the morning and afternoon sun would shine on the 53 homes for lower-income families.

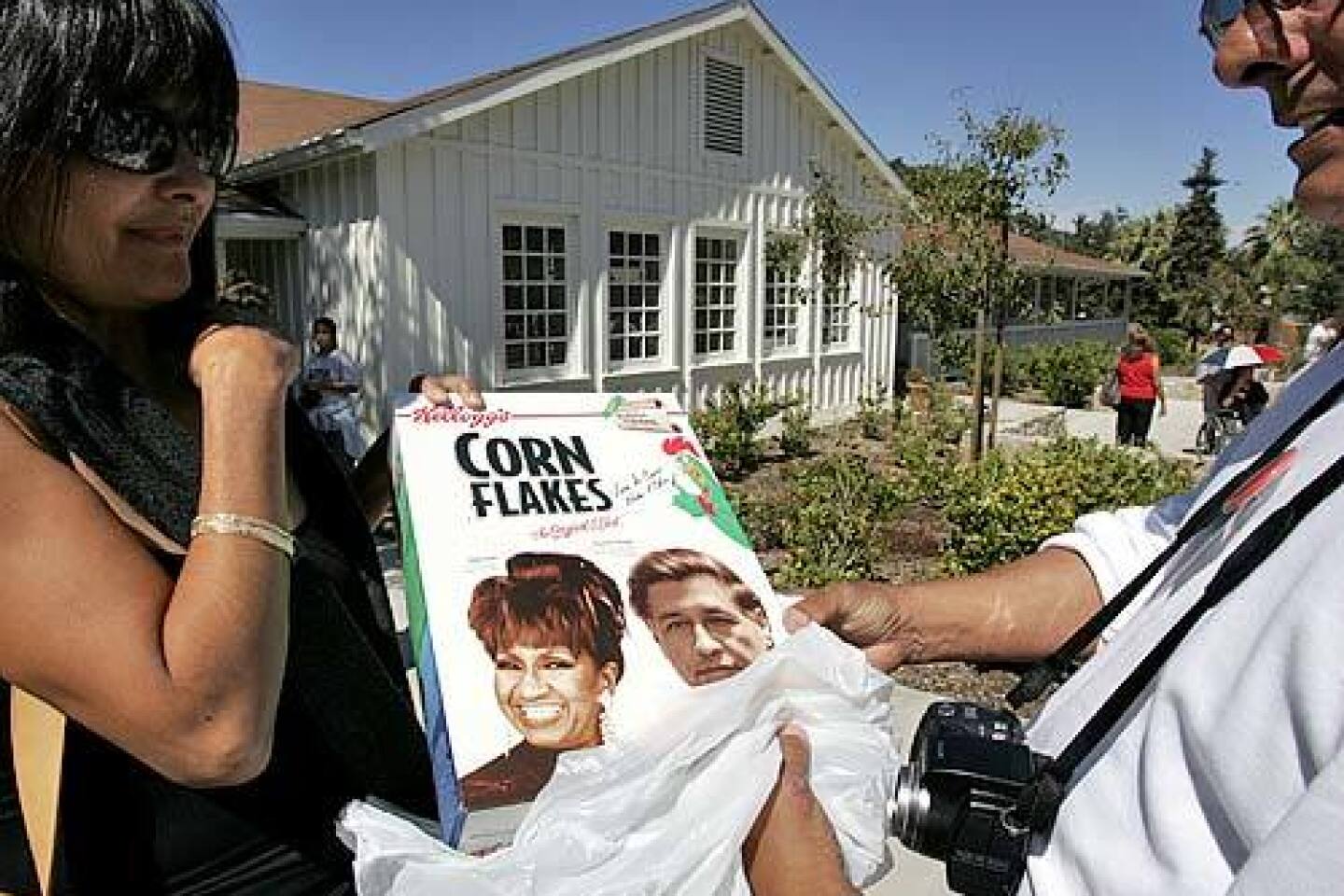

Almost a decade after the National Farm Workers Service Center had bought vacant land at a Fresno crossroads, the charity was ready to break ground on the affordable housing project called La Estancia.

Then the plans were abruptly scrapped.

Paul Chavez, president of the Service Center, decided the plot had appreciated so much it made more sense to sell. He did not have to look far for a willing buyer: Emilio Huerta, the Service Center’s lawyer, worked in the office next door.

FOR THE RECORD:

UFW —A series last month on the United Farm Workers contained three factual errors about the history of the labor union and its related organizations. Health clinics operated during the 1970s were run by the UFW-affiliated nonprofit National Farm Workers Health Group, not the union directly, as reported Jan. 8. UFW officials said that a Fresno developer who partnered with Cesar Chavez to build for-profit housing donated his services and did not split the profits from the developments, as reported Jan. 9. And UFW officials said a school bus abandoned in a back field at union headquarters was not one of the buses used to transport boycott volunteers across the country in the 1970s, as stated in the Jan. 9 article, but was left by a peace activist who never returned to claim it. In addition, the Jan. 8 article reported that the UFW “board deleted all specific references in the UFW constitution to agricultural workers, including the preamble.” To clarify: The board deleted the entire preamble and amended the constitution to include all categories of workers, so that the UFW constitution no longer applied only to agricultural workers and related laborers.

In May 2004, Huerta formed a private corporation called Landmark Residential. Three months later, Landmark bought the Fresno parcel from the Service Center for $1.8 million.

The day they closed the sale, Huerta and his partners had already agreed to sell the land for $2.9 million to a local developer, according to county records — reaping a profit of $1.1 million.

The insider deal is one example of how leaders of the UFW and the groups they call the Farm Worker Movement have steered money to friends and relatives at the expense of the charities they serve.

Some other recent transactions illustrate their penchant for doing business with their friends:

A UFW-related charity rented space last fall in a building owned by UFW Secretary/Treasurer Tanis Ybarra, who also sits on the charity’s board. Ybarra said he leases the building, in Parlier near Fresno, to his son Arturo.

The charity’s executive director, Nora Benavides, said she sent her staff to talk with Arturo Ybarra because he was well-connected in the area, and he offered to make space alongside his mother Martha’s tax preparation business. Benavides said it is convenient for the community organizing group’s clients: “We say, hey, listen, there’s Martha here who’s preparing taxes if you need it . We don’t push it, we just let people know it is available.”

Benavides said she formalized the rental arrangement to avoid any conflicts of interest. The move was never discussed by the charity’s board, which Tanis Ybarra said doesn’t “micromanage” such decisions.

The Service Center sold the UFW a Craftsman-style house in West Los Angeles that once housed dozens of boycott volunteers during the height of the union’s organizing activity. The UFW allowed friends to live there rent free, then sold it in 2004 to a daughter of UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta for $200,000 — about half the market price for comparable houses at the time, according to county records.

Huerta said that when she heard the UFW was going to sell the house, she asked to buy it because of its historic significance to the movement and her family. Because she had not taken a salary or received a pension during her years working for the UFW, the union gave her a break on the price, she and UFW President Arturo Rodriguez said.

Charities, exempt from paying taxes because they serve a public good, have a legal responsibility to obtain the best possible deal. They are required to disclose transactions with related groups or individuals and to be able to defend such decisions as cost-effective.

In the case of La Estancia, Paul Chavez said Landmark matched a competitor’s bid and was ready to pay the full $1.8 million in cash. He said he was unaware that Landmark flipped the property at a significant profit.

“What you have is a deal in which the charity obviously was paid a million dollars less than what the property was worth,” said Marcus Owens, an attorney who formerly headed the Internal Revenue Service division that oversees tax-exempt groups. “That’s a lot of money.”

The Players

Emilio Huerta and Paul Chavez have been friends since childhood, when they roamed the grounds around the building where they now work — the compound in the Tehachapi Mountains where Paul’s father, Cesar, and Emilio’s mother, Dolores, built the United Farm Workers union.Emilio, the fourth of 11 children, grew up in a series of surrogate homes as his mother negotiated contracts, organized strikes and lobbied in Sacramento and Washington. He dropped out of high school and went to work full time for the UFW.

At 17, Emilio worked as a graphic artist in the UFW print shop, alongside Paul, who worked as a printer. A few years later, Cesar Chavez tapped the two to attend a negotiation school set up to groom the next generation of union leaders. At the time, Huerta said he had no idea why he was chosen; later, he tied it to an ongoing battle over the departure of the UFW’s legal staff. “Part of it was Cesar making a point: He could teach anyone to be a negotiator,” Huerta said.

In 1990, Paul Chavez took over the Service Center and began an ambitious affordable housing program; after attending college and law school, Emilio Huerta joined him. Huerta became the secretary of the corporation in 1993, serving in that position for the next decade. The next year he became the general counsel, a job he performed first as an employee and later as an independent contractor.

For several years beginning in 2000, Huerta’s firm was paid more than $120,000 as a consultant to the Service Center. As an independent lawyer, Huerta bills for work on individual housing projects built by Service Center subsidiaries; a 2001 contract gave his hourly rate as $200.

In the 1990s, Chavez and Huerta hooked up with another high school friend who grew up in the UFW movement. Billy Encinas had started a small development company in San Diego and specialized in affordable housing projects.

Chavez had access to financing, thanks to the UFW’s political clout and the Service Center’s track record; Encinas had connections to projects, particularly in Texas, a state that Service Center leaders were desperate to move into as they fashioned themselves into a broader Latino advocacy group.

Encinas and the Service Center teamed up and went on to develop housing projects in California and Texas with subsidies from the state and federal governments.

The Land

In the early 1980s, as Cesar Chavez was struggling to find ways to finance services for farmworkers, a Fresno businessman had approached him with a proposition: Develop housing jointly and split the profits.“He said, ‘I know how to make money; I’d like to help out,’ ” Paul Chavez recalled about Celestino Aguilar, now a Fresno appraiser. “He’s the one who really talked about housing as an investment.”

The partnership, which built and sold some upscale houses and then apartment complexes and commercial strip malls, was the UFW’s first foray into development.

Later the union built housing for farmworkers; in more recent years under Paul Chavez’s leadership the Service Center has built and bought affordable housing aimed at lower-income Latinos — though not, for the most part, farmworkers.

The first partnership Cesar Chavez formed with Aguilar was called American Liberty Investments, and in 1993 the corporation bought a 12-acre plot in a sparsely developed area on the west side of Fresno for $316,000. A few years later, the Service Center took ownership.

Community opposition scuttled various development plans, including a sale to the high school that had been built across the street. Residents also opposed the Service Center’s plan to rezone the site and build multiple units, but the Service Center persisted and eventually won approval.

After drawing up plans for a town house complex, the Service Center tried to get a state grant earmarked for farmworker housing. But state officials rejected the application, saying the proposed home prices would require that families earn at least $29,245 a year, an unrealistic income for farmworkers. State housing officials also said the proposed price, $115,166 for a three-bedroom home, was too high for the area and the homes could be priced more reasonably if the Service Center did not insist on collecting an “excessive” development fee of $10,000 per home.

Eventually, the Service Center arranged other financing and announced in a newsletter that construction would begin by the end of 2003. By then, the real estate market had exploded. The demand for single-family homes was high, particularly in that area of Fresno. A parcel that had been through the time-consuming process of rezoning was worth significantly more.

A contractor the Service Center was working with offered to buy the site and build the subdivision himself.

The Deal

Emilio Huerta was very familiar with “the dirt,” as he called the Fresno parcel. He had tried to negotiate the sale to the school district years before. Though his current role didn’t involve him directly in the Service Center’s housing department, Huerta often drew on his experience to offer Chavez advice on property and land values.After a decade with the Service Center — much longer than he had intended to stay — Huerta wanted to move on. In the fall of 2003, he began working privately with Encinas on a plan to build single-family housing.

During 2004, Huerta juggled the new venture with his responsibilities for the Service Center, which he still served as counsel. He had been traveling around the country with Encinas, making plans, when they heard Chavez wanted to sell the Fresno land. It seemed like an opportunity to launch the new business.

“Paul came and said, ‘I’m willing to sell this land,’ ” Huerta said. Chavez said he had another buyer lined up, and Huerta asked for a chance to compete. “I said, ‘If we’re allowed, I’d like to make an offer.’ ”

Encinas and Huerta consulted with another partner, Daniel Rigney, a veteran homebuilder now working as a senior vice president at Sunamerica Affordable Housing Corp., and Landmark made a bid.

Chavez opted for the businessman who made the first offer and asked Huerta to draw up the contract.

Within days, that deal fell through. Chavez went back to Landmark.

Huerta said he pointed out several times that the value of the land would increase if the Service Center waited and finished the site plan, negotiating such details as sewers, curbs and utility hookups. “Paul said, ‘We need some money.’ ” Huerta recalled. “I said, ‘Paul, it will be much more valuable if it has a map.’ ”

Chavez needed the cash right away because he was interested in bidding on a new radio station that could expand Radio Campesina into the Sierra foothills. If the Service Center won the bid, it would need to produce a lot of cash in a hurry.

He pulled his friend aside and warned Huerta not to bid if he couldn’t make good on the deal, Huerta said. “I didn’t see it as some sort of opportunity to cash out,” he said. “I saw it as an opportunity to go ahead and prove to Paul and the Service Center that we can put land deals together. This is my chance to prove to Paul and the Service Center that I can produce — that’s how I saw it.”

Chavez asked for $1.8 million and imposed a tight timetable and other restrictions. Landmark agreed to all Chavez’s conditions.

“They had a high bid; we just stepped in and took it at that price,” said Rigney. “I thought, there’s still some opportunity there; we can build it out, make some money — a little retirement nest egg.”

Rigney called a loan broker he had done business with before and asked him to see what kind of deal he could put together to finance the purchase. The broker called a week later: Another client, Ennis Homes, was looking for more land to develop; would Landmark be interested in selling?

“I said to my loan broker, ‘If you can sell for x, sell,’ ” Rigney recalled. “I threw something way up high on the wall, and they came back and took it.”

By the time Landmark bought the property, the partners had an agreement to resell the land to Ennis, Rigney said. County records show the Landmark-Ennis deed is dated Aug. 25, the day before the deed on Landmark’s purchase from the Service Center.

Chavez said he saw no conflict in the sale. When first asked about it, he expressed surprise that Huerta was involved. “He had given me notice that he was leaving; we talked, and he had a change of mind,” Chavez said in an interview. “He said, ‘You know what, I’ve put too much into Service Center.’ My understanding was that he severed the relationship” with Encinas.

Huerta said there was full disclosure and that the Service Center board, which approved the sale, was aware that he and Encinas were partners in Landmark.

In a written clarification to The Times, Chavez later said that Huerta had continued to do business with Encinas but that it was not a conflict because Huerta resigned as secretary of the Service Center in October 2003, though he continued to do legal work.

The distinction could be significant for the Internal Revenue Service, which levies sanctions on deals where officers or key officials of a charity profit unduly from a transaction with the organization.

“It really was a very, very clean deal: Buying from one and planning to do something, then somebody comes in and offers you a deal,” Rigney said. He estimated his profit could have been double if Landmark had decided to develop the houses itself rather than sell. But the offer from Ennis had been too tempting to turn down: “I guess I shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth.”

Huerta said he decided after the sale to part ways with Encinas because of philosophical differences, and he is in the process of dissolving Landmark. “We had a national plan. They were dreams,” he said.

The Service Center tried to acquire the new radio station but was outbid. Last January, the Service Center board reappointed Huerta as secretary, Chavez said, adding that Huerta does much of his legal work for the organization pro bono.

Calling Chavez his best friend since childhood, Huerta said: “No amount of money is worth jeopardizing that. It wasn’t because I saw big dollar signs. As an attorney, I could make more money than here. My reputation was on the line. I wanted to do housing. I still want to.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.