War orphan’s search for her roots begins with a name: Precious Pearl

The name in an old passport leads Kimberly Mitchell to an orphanage in Vietnam and a former South Vietnamese soldier.

Standing in the battlefield, the young South Vietnamese soldier was getting ready to blow up a bridge before Viet Cong forces could cross when an old man staggered his way, carrying a bundle.

The stranger handed him a conical straw hat. There was a baby inside.

The man said he had found the little girl clutching a dead woman, still trying to nurse.

"I can't go on any longer," he said. "Please bring her to safety. She is desperately hungry."

It was wartime in Vietnam, 1972, and 22-year-old Bao Tran had been trying to focus on just one thing: igniting the My Chanh Bridge. But now he stood frozen, staring at the pale, thin child in stained cotton.

When he asked his commanding officer what to do, the reply was straightforward: "You take care of her."

So Tran set off for a nunnery 37 miles away. He walked, he rode a bus. When the child began to whimper, he poured drops of water from his thermos, letting her lick it from his finger.

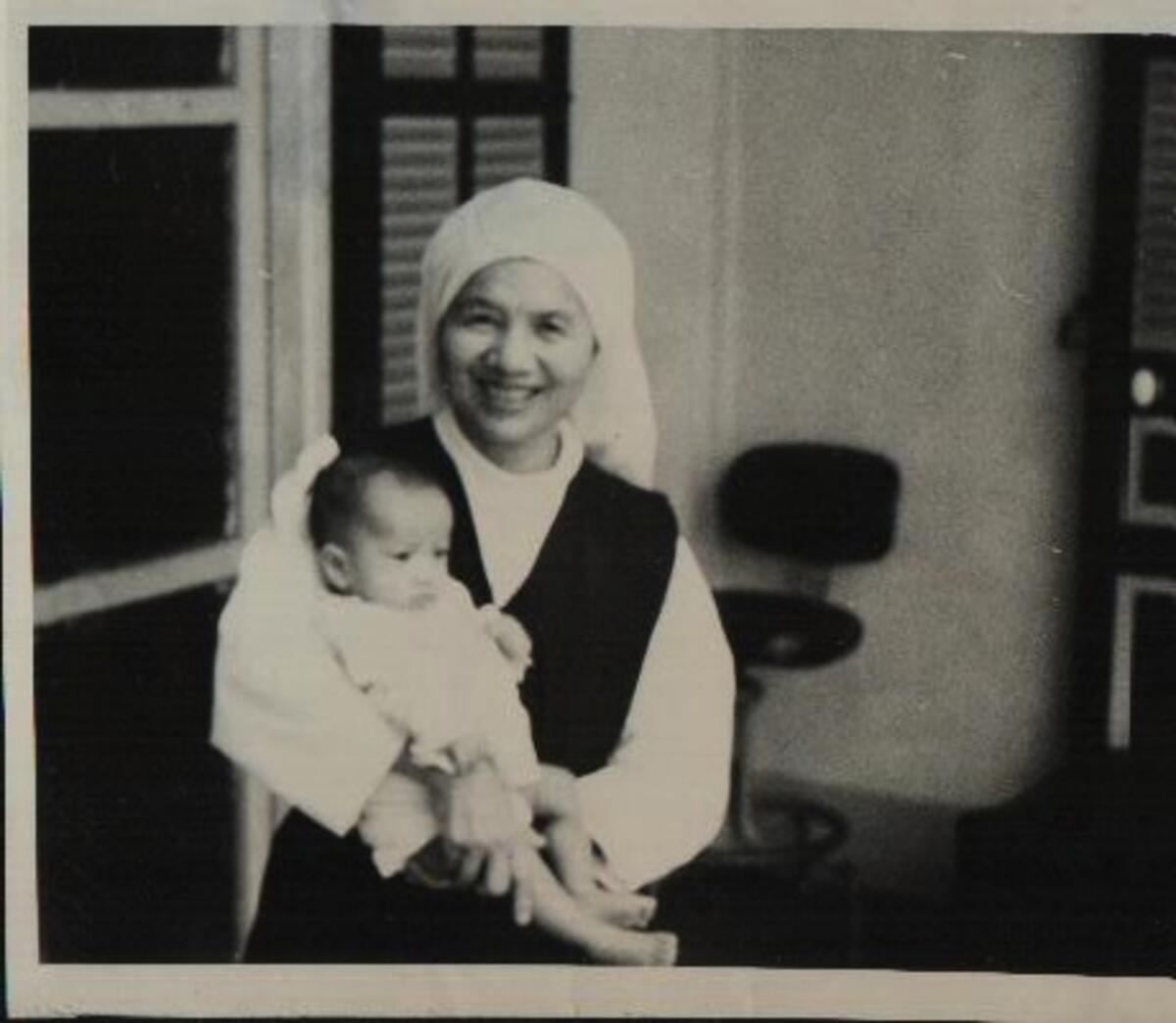

At the Sacred Heart orphanage in the coastal town of Da Nang, the head sister greeted him at the front door.

"You must fulfill your responsibility," Sister Angela Nguyen told Tran. "You must give her something of yourself. What would you like to call her?"

He gave her his last name, then added: Ngoc Bich.

Precious Pearl.

A faded photograph was tucked into her luggage as Kimberly Mitchell boarded a plane in 2011, bound for a country where she didn't know the language or the culture.

It was her first trip to Vietnam since she had left as a child, a celebration of turning 40 but also a voyage to unravel the mysteries of her past.

Traveling with three friends, she had planned to visit the nunnery from her childhood, but the Sacred Heart orphanage, now with peeling paint, had been turned into a retirement home for government workers.

But Mitchell's friends had secretly found the orphanage's new location in Da Nang. It would be a birthday surprise.

They told her they were going to a street market. Instead, they drove past it to a building in the center of town. A nun introduced herself.

"I am Sister Mary," she said. "Consider this your home."

As a novice in 1972, Sister Mary Huong Tran used to come to Sacred Heart on Sundays to care for unclaimed babies. At the time, American officers from a nearby air base would visit, bringing gifts of candy or toys.

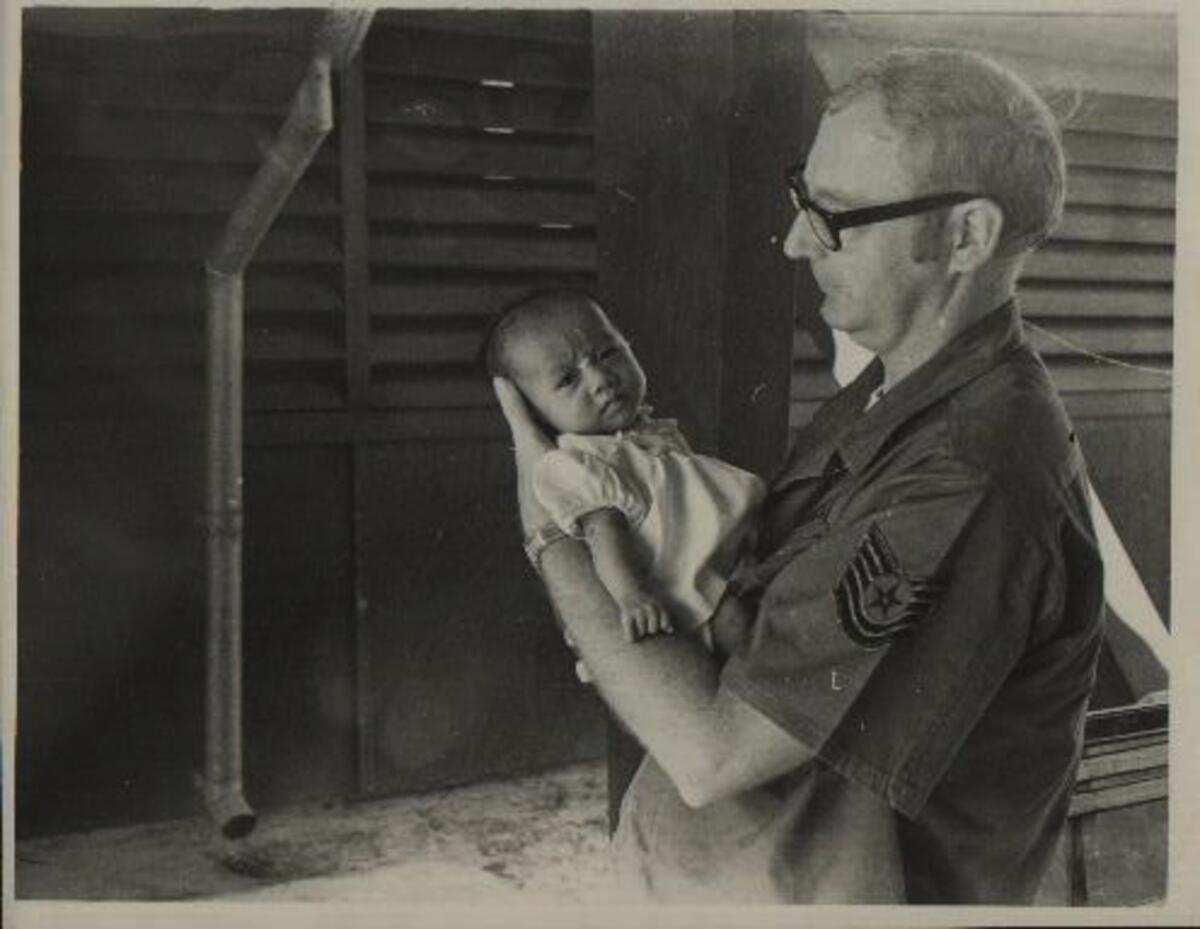

James Mitchell, an Air Force tech sergeant stationed in Vietnam during the war, holds Tran Thi Ngoc Bich. Amid the destruction of war, he hoped to offer her a new life. (Kimberly Mitchell) More photos

The officers delighted in playing with the kids. Some asked about their health, or about bringing them home.

"We had so many displaced children," Sister Mary told Mitchell. "We could not turn them away.... And when the military people called, if they have a certain feeling about a child, we would find out about their families — did everyone agree to taking the child, did the person who would become a parent have a good heart — before we could decide to let them go to their homeland with one of the children.

"Why are you here today?" she asked.

Mitchell handed over an old passport, the black-and-white photo showing the face of a 10-month-old girl.

"This was me," she said. "I believe I came from here." She pointed to her birth name.

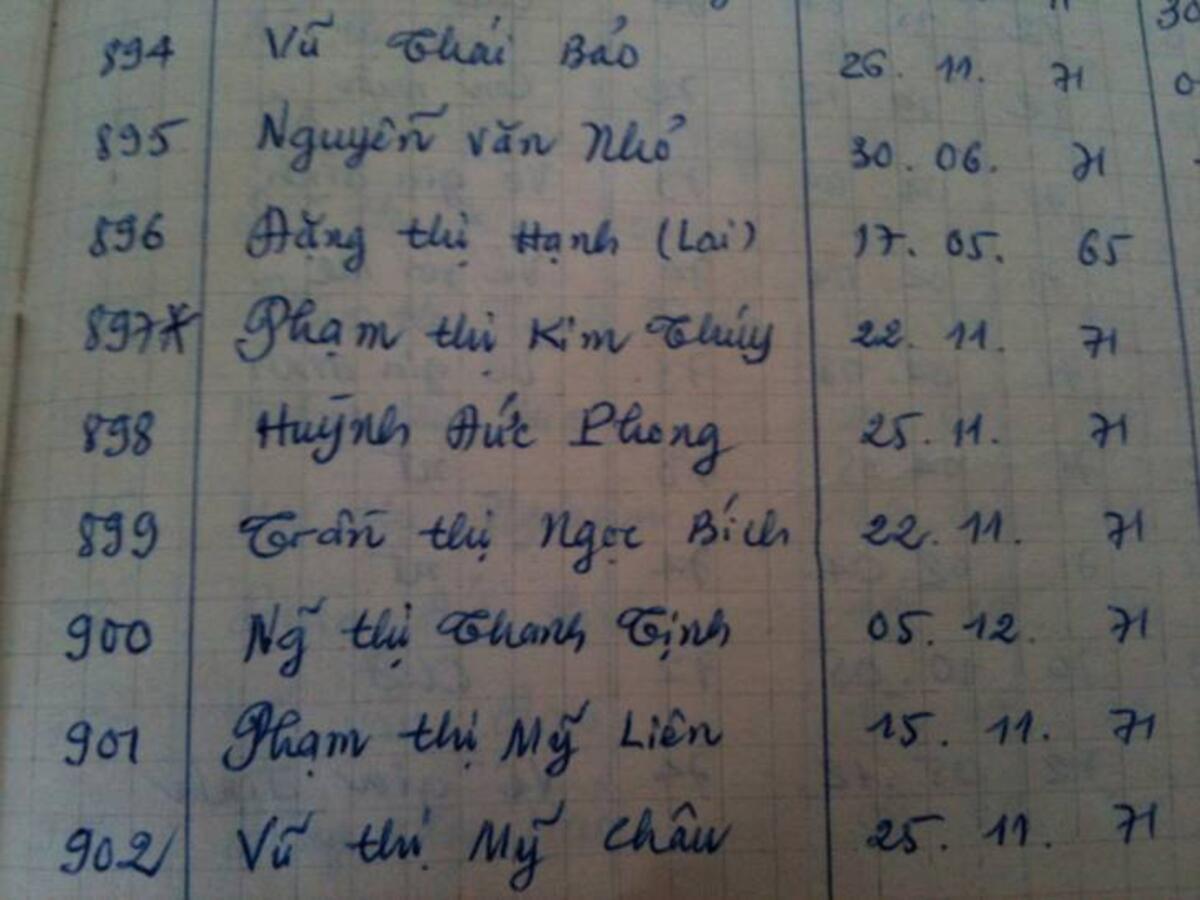

Sister Mary stared at the image, taking her time as if searching her own memory. Then, she took out the record books. Flipping the delicate pages, she found baby #899 — Tran Thi Ngoc Bich. Precious Pearl.

"What do you know about your background?" the nun asked.

This much Mitchell knew: In the chaos of war, an Air Force tech sergeant named James Mitchell had witnessed so much destruction, he hoped to be able to offer someone a new life.

One child drew him to her. Precious Pearl. Soon, he would take her to Saigon, fulfilling the paperwork needed for her passport to travel to America in September 1972.

Mitchell and his wife, Lucy, a teacher, would tell their daughter the only thing they ever heard: A man brought the baby to the orphanage and named her Precious Pearl. The sisters never saw the man again.

"I always wondered: What were the conditions that led me to being abandoned?" Kimberly Mitchell said. "Did my birth mother or her family have no choice?"

Bao Tran longed to return to the orphanage and check on Precious Pearl's progress. But he never could — North Vietnamese forces had turned the war in their favor.

The record books at the Sacred Heart orphanage list baby #899: Tran Thi Ngoc Bich. (Kimberly Mitchell) More photos

By war's end, in April 1975, Communist victors shipped him to a reeducation camp, jailing him for six years. After his release, Tran, desperate to support his family, latched onto the job of a cyclo driver, barely scraping by.

In 1994, under a U.S. State Department program to resettle former South Vietnamese soldiers, he and his family landed in the United States — heading straight for Albuquerque. Tran remains there with his wife and two of his three children.

Yet through the decades, he couldn't forget the other child. Whatever happened to Precious Pearl?

Then one day in May 2012, he picked up a free sample of a Vietnamese-language magazine based in New Jersey. In it, he saw an article about a career Navy officer named Kimberly Mitchell and her search into her past.

The story cited the name on her old passport: Precious Pearl.

"I thought: This has to be that baby. Who else could it be?" Tran said. "I had to find a way to tell her she was not abandoned — she was rescued. She didn't have to fear that no one wanted her."

I had to find a way to tell her she was not abandoned — she was rescued.”— Bao Tran, ex-soldier

Lacking English, Tran, who spent years working in construction, asked a friend with a brother-in-law in the Navy to help him find Mitchell. Using the Internet and the inside source, they searched for months until they finally found her phone number.

Mitchell thought their calls were all a prank, a hurtful effort to falsely raise her hopes. She refused to respond until one afternoon, she heard a message: "Please, please pick up the phone. We will call back in 20 minutes."

Tran's Navy friend came on the line, translating his story about rescuing Mitchell. Mitchell asked them to send it to her in writing, testing to see if the details would change.

When the letter arrived, Mitchell read it carefully, her emotions welling up. Maybe, she thought, just maybe...

"He sounded very sincere, very determined that I was the child he held," she said.

The pair traded information for months, matching her adoption date to the time when Tran was a soldier. He told her that by his calculation, she would have been born in late 1971 and indeed, the baby passport she clung to showed her birth month as November 1971.

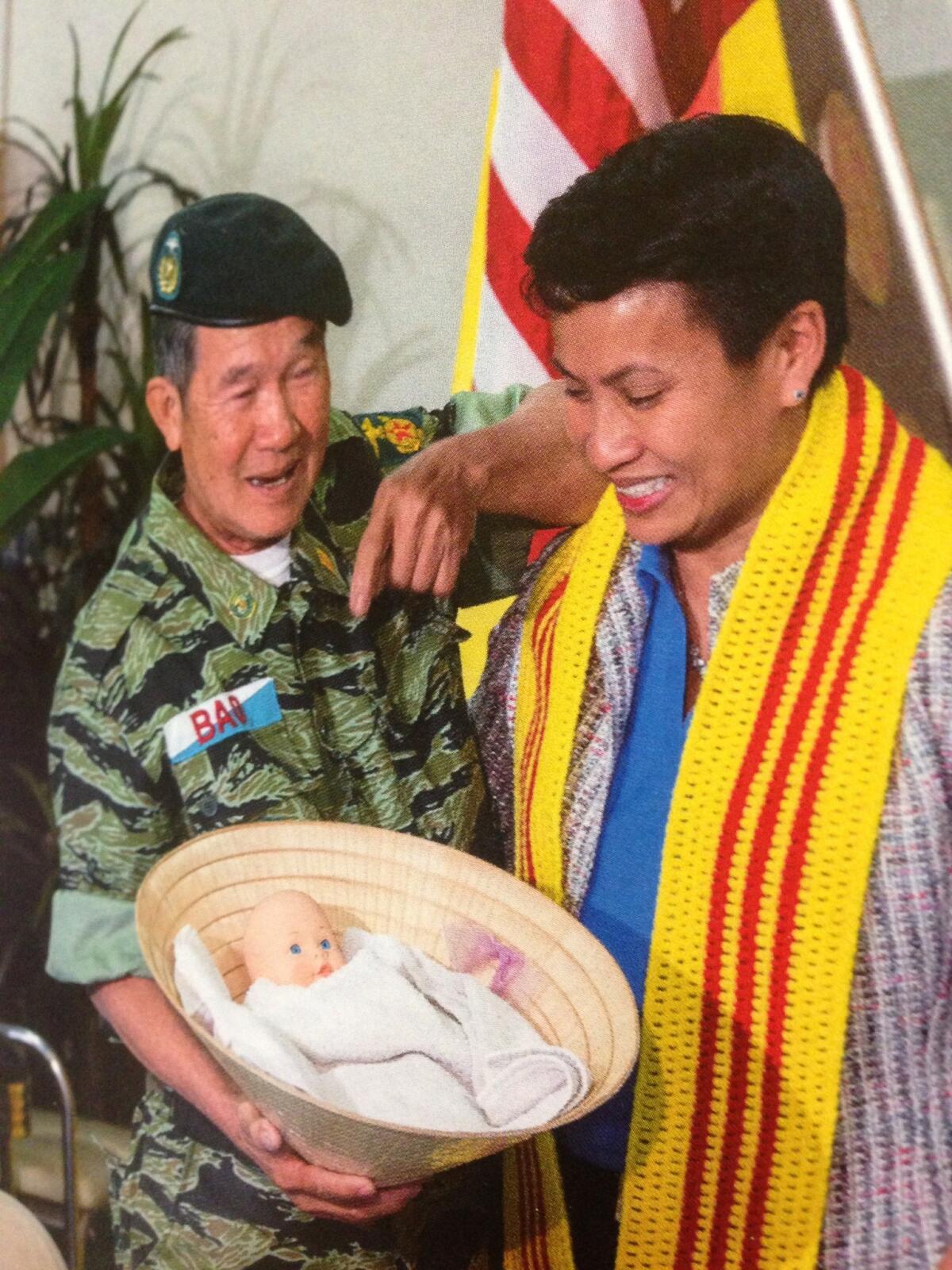

A family album photo shows Bao Tran and Kimberly Mitchell at their reunion in 2013. He gave her a conical hat with a doll inside. "This is how I found you," he told her. (Anh Do / Los Angeles Times) More photos

She told him about her childhood. She had grown up in Wisconsin, where she learned how to milk cows and make cheese on her family's farm. She never thought about whether she was different from those around her.

But when she started grade school, when she found out that she'd been adopted, the questions started.

"I wondered what happened to my birth parents. Did they have other children? Did they have food? How did they feel after I was gone?

"I did not know my birth mother would be gone too."

Bao Tran, dressed in fatigues, his gray hair covered by a beret, frowned. Then smiled.

A tanned woman with close-cropped curls surged forward. They barely heard the speeches in English and Vietnamese inside the room housing the Vietnamese Assn. of New Mexico. Forty-one years after they last met, the two embraced. Tran, 62, cried.

As cameras from the Albuquerque TV station flashed, Mitchell turned to him, saying, "He is my hero."

Again, she put her arms around Tran, and he produced a conical straw hat with a doll belonging to his grandchild. "This is how I found you," he told her.

"I was thinking, 'Why did this man save me?'" Mitchell recalled. "He must have great compassion and love beyond what we could understand."

Tran said: "I always hoped she grew up with a wonderful life. In my own life, I only want to share with her that she had a safe start to that life."

Since the reunion in March 2013, the two have had monthly Skype sessions that at times are as ordinary as a conversation a father and daughter might have.

They talk about her 17 years in the Navy, rising to lieutenant commander before retiring. They talk about her move to Washington, where she works with the Dixon Center, a nonprofit helping veterans and their families transition to civilian life. They talk about her hectic travel schedule.

"She's like a bird — flying here, everywhere. She cannot stay still," Tran likes to say, in the half-chiding, indulgent tones parents use when they talk about a favored child. "I always ask, 'Where do you go to next, little bird?'"

Mitchell shared more news. Officials with the Vietnam War Commemoration Committee, marking 2014 as the conflict's 50th anniversary, chose her as spokeswoman.

"It's a thrill to use my story to teach a new generation about the war," Mitchell said. "I will tell them, this story starts with a name."

Follow Anh Do (@newsterrier) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

In Syria, war is woven into childhood

We have become reliant much more on kids. ...But this is not a good thing.”

Ex-lawyer is on a mission to keep schools fair

A large number of school districts were quite brazenly ignoring the law.”

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.