This opera’s drama isn’t only onstage

Onstage in a UCLA auditorium, tenor Rickard Roudebush intones the solemn words of the Episcopal funeral rite: “I am the resurrection and the life. . . . He that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live. Amen!”

A chamber opera called “The First Lady” is in rehearsal. Roudebush, one of the work’s creators, sings the small but affecting role of the priest who officiated at the White House funeral of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The funeral scene is drenched in operatic grief, and the irony is not lost on Roudebush. Twenty-two years ago, doctors advised him to quickly get his affairs in order, take a last trip to Europe and plan his own funeral.

::

Friends remarked on Roudebush’s pallor in August 1988, but it wasn’t until late November that he wrote in his diary: “Up early and did laundry. Alarming pounding of heart and weakness in legs climbing stairs.”

Despite the symptoms, he drove to the Napa Valley from Los Angeles to spend Thanksgiving with his brother and sister-in-law. She whisked him off to a doctor. Tests revealed that he was inexplicably anemic.

The doctor advised Roudebush to check in to a hospital immediately. But there was one problem: He had a ticket the next night to see Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” at the San Francisco Opera, and he wasn’t about to miss it.

The day after seeing the opera, Roudebush made the six-hour drive back to L.A. alone and went to the emergency room at Kaiser Permanente Panorama City Medical Center. The doctor on duty took one look at his blood-test results and admitted him. A colonoscopy found a tumor the size of a tennis ball. He needed surgery right away.

But there was one problem: Roudebush had a ticket to see Los Angeles Opera’s production of Alban Berg’s “Wozzeck.” He wasn’t about to miss it.

Roudebush, 62, developed a passion for arias and libretti at an early age. His parents’ tastes ran to Chubby Checker and Fats Domino, but Roudebush couldn’t get enough of 78-rpm recordings of the coloratura soprano Amelita Galli-Curci and tenor Tito Schipa. His father, who laid linoleum floors, would not allow his son to study violin, saying it wasn’t practical.

At Culver City Junior High, he befriended Kenneth Wells, a classmate from a musical Baptist family. (Wells’ grandfather, Clarence Wells, was choir director for evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson’s Angelus Temple in the 1930s.)

Wells had begun plunking away at an untuned honky-tonk piano at age 9. He started composing at 12 and later formed a gospel singing group. For his 13th birthday, his father brought home an “as is” Hammond organ that they repaired. His father installed a speaker in a wall so that neighbors could hear the boy play. Occasionally, someone would knock on the door and request “Lady of Spain.”

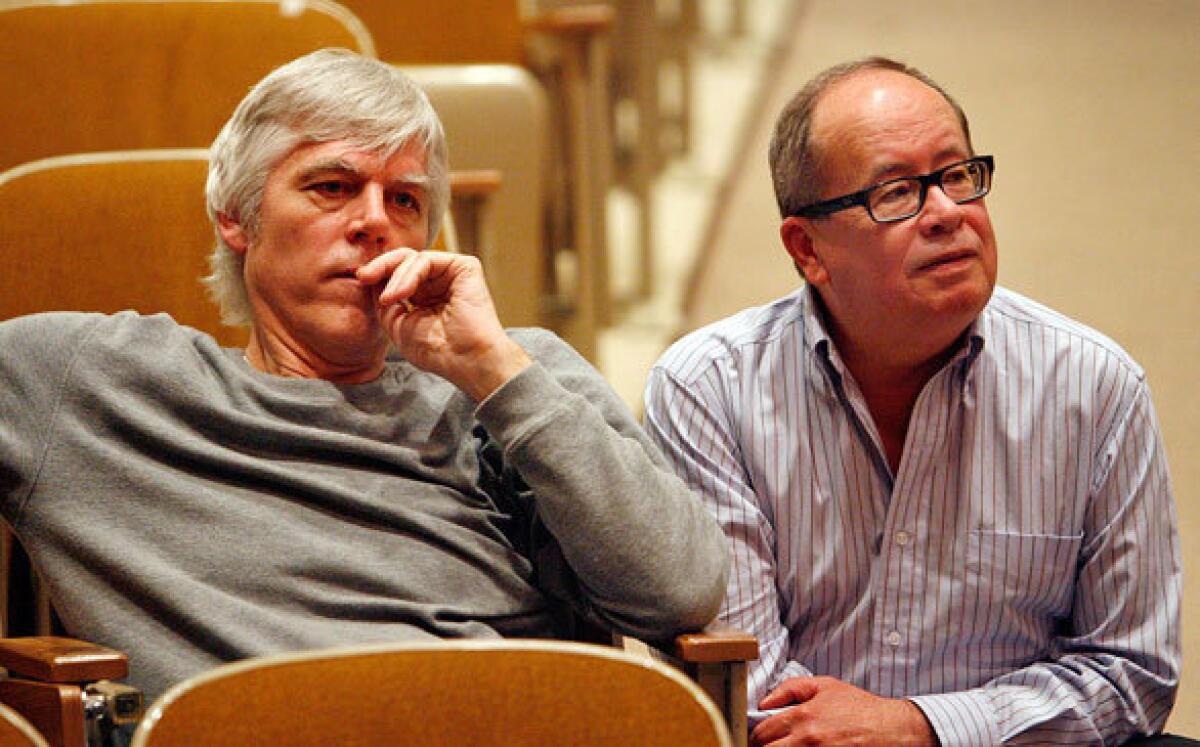

“We’d go Christmas caroling as a family and sing in 16-part harmony,” said Wells, 61, now a psychiatrist, professor and researcher at UCLA and a senior scientist at Rand Corp.

As their classmates grooved to the Beach Boys and Motown, Roudebush spun for Wells his recordings of Joan Sutherland, Maria Callas and other opera greats.

After high school, Wells went to Occidental College, then to medical school at UC San Francisco and finally to UCLA, where he earned a master’s degree in public health.

Roudebush took a different path, studying English at California State College at Long Beach and working at his father’s hardware store. They attended an occasional recital or opera together.

The usually reserved Roudebush was fearless about going backstage. After one performance, the two presented themselves to Sutherland and a rising star named Marilyn Horne. When Sutherland asked whether they sang, Wells replied that he was a tenor.

“Here is a tenor you should meet,” she said, turning to her left. “He is going to be famous someday.” It was Placido Domingo.

The friends lost touch for a time, but in late 1978, Wells enlisted Roudebush for a new choral group, later dubbed the Mansfield Chamber Singers.

“Can you sing?” Wells asked.

“In the shower,” Roudebush replied.

Wells was thrilled to discover after all these years that his friend had a voice. Roudebush began taking lessons. He never tried to make a living as a singer (he is a medical transcriptionist at UCLA), but he has appeared as a soloist with the Mansfield Chamber Singers and has performed in operas with Los Angeles-area groups.

Then, in 1988, he was diagnosed with colon cancer. Not long after his surgery, Roudebush had a heart-to-heart with his oncologist. She told him he had about a year to live. “She advised me to get my affairs in order, take a trip to Europe perhaps. . . . and then face my inevitable death with everything taken care of in advance,” he recalled.

Wells insisted on a second opinion. As a long shot, Michael Rosove, a UCLA doctor, recommended a promising experimental combination of drugs.

Roudebush said he was “resigned to dying,” but Wells begged him to try.

In early 1989, Roudebush closed the family business and began weekly chemotherapy. When the treatment ended six months later, Wells, Roudebush and Gayle Patterson, a Mansfield friend, celebrated by going to the Santa Fe Opera to see Francesco Cavalli’s “La Calisto” and Jules Massenet’s “Chérubin,” two rarely performed works.

At Patterson’s suggestion, they also visited El Santuario de Chimayo, a chapel north of Santa Fe purported to have therapeutic powers.

There, by the dried remnants of a healing spring, the three friends held hands and prayed. That night at dinner, Wells sprung on them his long-cherished dream of writing a libretto.

Patterson suggested Eleanor Roosevelt as a protagonist, given her perseverance through her husband’s infidelity, his death and criticism of her public role as first lady.

Over the next two years, Patterson did historical research, gleaning possible lyrics from speeches and other sources. After much discussion, the team focused on Eleanor, the Roosevelts’ daughter Anna and Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd, FDR’s mistress, who was with him just before he died. Wells sketched out the larger story and began drafting the libretto. Patterson, Roudebush and Wells’ son Matt are credited as co-librettists, but by all accounts Wells did the heavy lifting.

The libretto was copyrighted in 1992, a year Roudebush had never thought he’d reach.

In September 1995, Wells vowed to complete the opera. He worked for years in fits and starts, stealing moments from his medical research to revise the libretto and compose and orchestrate the music.

In his mind, the music is “very American,” an amalgamation of gospel, musical theater “and the sound of my mother’s voice reading poetry.” The opera includes some hummable moments, as well as variations on Dvorak, George M. Cohan’s “The Yankee Doodle Boy” and “Faith of Our Fathers,” a favorite hymn of FDR that was sung at his funeral.

The 2 1/2 -hour, two-act opera covers the period from FDR’s death from a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945, to VE Day, May 8, 1945, with some fictional elements.

On the day he collapses, FDR is in Warm Springs, Ga., with his longtime love, Lucy. In Washington, Eleanor learns of his “fainting spell,” but the president’s physician plays down its seriousness so that Lucy can leave unobserved.

While on the train later with FDR’s remains, Eleanor learns that Lucy was at the president’s side when he collapsed and that the affair had been encouraged by Anna. Eleanor’s grief turns to shock and betrayal. The opera captures the women’s resilience as they -- and the nation -- endure the loss.

Countless revisions later, the work -- with a chamber orchestra and vocalists from Los Angeles Opera and other groups -- will have its premiere Friday at the UCLA Semel Institute Auditorium. It will complement an academic symposium about coping with stress and catastrophe.

The UCLA Semel Institute Health Services Research Center, which Wells directs, contributed funds to produce the opera and the symposium. Needtheater (a rollicking young company founded by Matt Wells) designed and built the sets. The lectures and six performances are open to the public free of charge.

Wells can scarcely believe the opera will actually be performed.

“I didn’t start this expecting it to ever be produced,” he said. “I started it as a healing experience among friends.”

Roudebush, who knows something about resilience, had hoped to be in the audience for all six performances. But there was one problem: Wells, the friend who had saved his life, wanted the man who’d introduced him to opera to be in the opera. So Roudebush will sing in three of the performances.

And he will be in the audience for the other three, reveling in life, music and friendship.

“I’m very glad,” said Roudebush, who remains cancer-free, “I did not go to my death bed without singing this opera.”

For information about “The First Lady” and the symposium, and to reserve tickets, go to

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.