Relief is near on 60/91/215 interchange

On any given day, CHP Sgt. Joe Morrison sends officers out to a dozen accidents around the jammed intersection of the 60, 91 and 215 freeways in Riverside. He calls the interchange and the four miles of curving downhill freeway leading up to it from the east “a suicide drive.”

Off-duty, he and his wife won’t even drive through it. “We stay the heck away from that. It’s either backed up or there’s a big crash,” he said. “There’s always something.”

Every region in Southern California has its nightmare freeway interchange. In the San Fernando Valley, it’s the intersection of the 405 and 101. Orange County has “the Orange Crush” -- the convergence of the 5, 22 and 57. In the Inland Empire, the choke point is the junction of the 60, 91 and 215 near downtown Riverside. But relief is on the way for the 320,000 motorists who pass through the Riverside County interchange every day -- many on their way to Las Vegas, Palm Springs and San Diego or Lake Arrowhead.

A three-year, $317-million reconstruction project to upgrade the interchange and widen five miles of freeway around it will wrap up in six months. Caltrans officials plan to open two new connector ramps by year’s end, including one that soars 72 feet high and measures just over a mile long.

The improvements couldn’t come at a better time. Although Los Angeles and Orange counties remain the worst regions in the country for traffic delays, the Inland Empire and the area around Oxnard and Ventura are quickly catching up, according to a national study released Tuesday.

Researchers at the Texas Transportation Institute found that motorists in Los Angeles and Orange counties wasted an average of 72 hours in rush-hour traffic in 2005. In Riverside and San Bernardino counties, drivers wasted an average of 49 hours stuck in peak-period congestion during the same period -- an increase of 175% since 1995.

Before Caltrans started work on the 60/91/215 interchange in 2004, the junction was a relic of the late 1950s, when the Inland Empire’s population was about 750,000. Four looping connectors formed a “cloverleaf” interchange that carried motorists among thoroughfares, with a single merging lane for cars getting on and off the freeways.

But the structure couldn’t handle the crush of cars, trucks and motorcycles that came into Riverside and San Bernardino counties with the housing boom. Today, more than 4 million people live in the Inland Empire, with planners expecting 8.4 million residents by 2050. The number of motorists using the interchange has already doubled in the last five years.

At any given moment, the road is jammed with commuters, long-haul truckers, UC Riverside students and vacationers heading to Southern California’s mountains, deserts and beaches.

“It was an infamous interchange,” said Mike Bergevin, one of three Caltrans engineers overseeing the project. “It would plug up the freeway for miles before you got to it and then you’d crawl through, no matter which way you were going.”

During construction, the gridlock has become even worse.

Willie Delvalle, a court courier, drives through the interchange almost daily as he carries legal papers from Moreno Valley to downtown Riverside. On a bad day, the interchange and the backlog it creates can turn a seven-minute trip into a 30-minute crawl. “You just don’t move,” said Delvalle, 36, of Colton. “It’s like being on Hollywood Boulevard on a Saturday night, except nobody’s dressed up.”

Some of the drivers forced to use the unfinished interchange spend so much time stuck in traffic together that they end up bonding against impatient motorists who try to cut into connector lanes.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, drivers waiting to enter a connector loop from the westbound 60 to the 91 Freeway moved at a lethargic two or three car lengths a minute. When a small sedan kept an SUV from nosing its way into line late in the game, drivers who’d been waiting in line grinned into their rear-view mirrors and gave the sedan driver enthusiastic thumbs-ups to applaud her stubbornness.

Caltrans engineers say the project should ease traffic woes for a while. But whether the interchange will ever shake its reputation as a choke point remains an open question.

Gwen Galvain, 52, of Riverside feels lucky that she works near home. Unless she’s visiting friends in Murrieta, she steers clear of the interchange.

“One accident and you’re stuck for hours,” she said recently. “It’s like a parking lot. It’s stopped. You’re miserable.”

And there are plenty of accidents. Sgt. Morrison of the California Highway Patrol estimates that his officers respond to about 30 calls a day in and around the interchange. They handle fender-benders, stalled cars and the occasional 20-car pileup.

The four-mile, curving stretch between Riverside and Moreno Valley has always carried a treacherous mix of cars and long-haul trucks, Morrison said.

The construction hasn’t made driving conditions any easier. Much of the freeway is lined with concrete barriers where Caltrans crews are building new lanes and a truck bypass. But the so-called K-rails often prompt drivers to drift into other lanes and cause accidents, Morrison said.

In 2006, there were eight fatal collisions -- three more than the previous two years combined. He thought things would improve after the construction was over.

“Everybody’s always in a hurry, and nobody realizes they have to slow down,” Morrison said. “It’s posted as a construction zone, but they go flying through anyway. It’s just one bad place.”

Even the Caltrans engineers overseeing the reconstruction effort avoid the project site after work. To get home to Tustin from his office in San Bernardino, Bergevin, the civil engineer, often takes a circuitous route along the 10 Freeway rather than pass through the interchange.

The 60/91/215 reconstruction project is about six times as big as any other built in the region.

In 2003, when the project was put out to bid, it was Southern California’s most expensive freeway undertaking. When the work is finished, Caltrans crews will have built 11 bridges, 84 walls and raised a half-mile section of the 91 Freeway by 30 feet. Transportation planners designed the interchange to handle traffic projections through the next 20 years.

As Bergevin leaned against the railing near the top of the 90-foot flyover on a recent evening, the engineer remembered the thrill of being chosen to run one-third of the project. His portion includes the flyover -- “I got the eye candy of the project,” he said.

But as with any big construction job, there were many hiccups -- and headaches -- along the way. Bergevin had to deal with construction material shortages, weather delays and strange time constraints.

From Oct. 1 to Jan. 1, he was forbidden from doing any work that might slow down deliveries along a set of railroad tracks that ran under the freeway. Caltrans promised the railroad company that holiday shoppers would be able to buy their PlayStations and TMX Elmos on time.

Major surgery on the freeways had to be done at night.

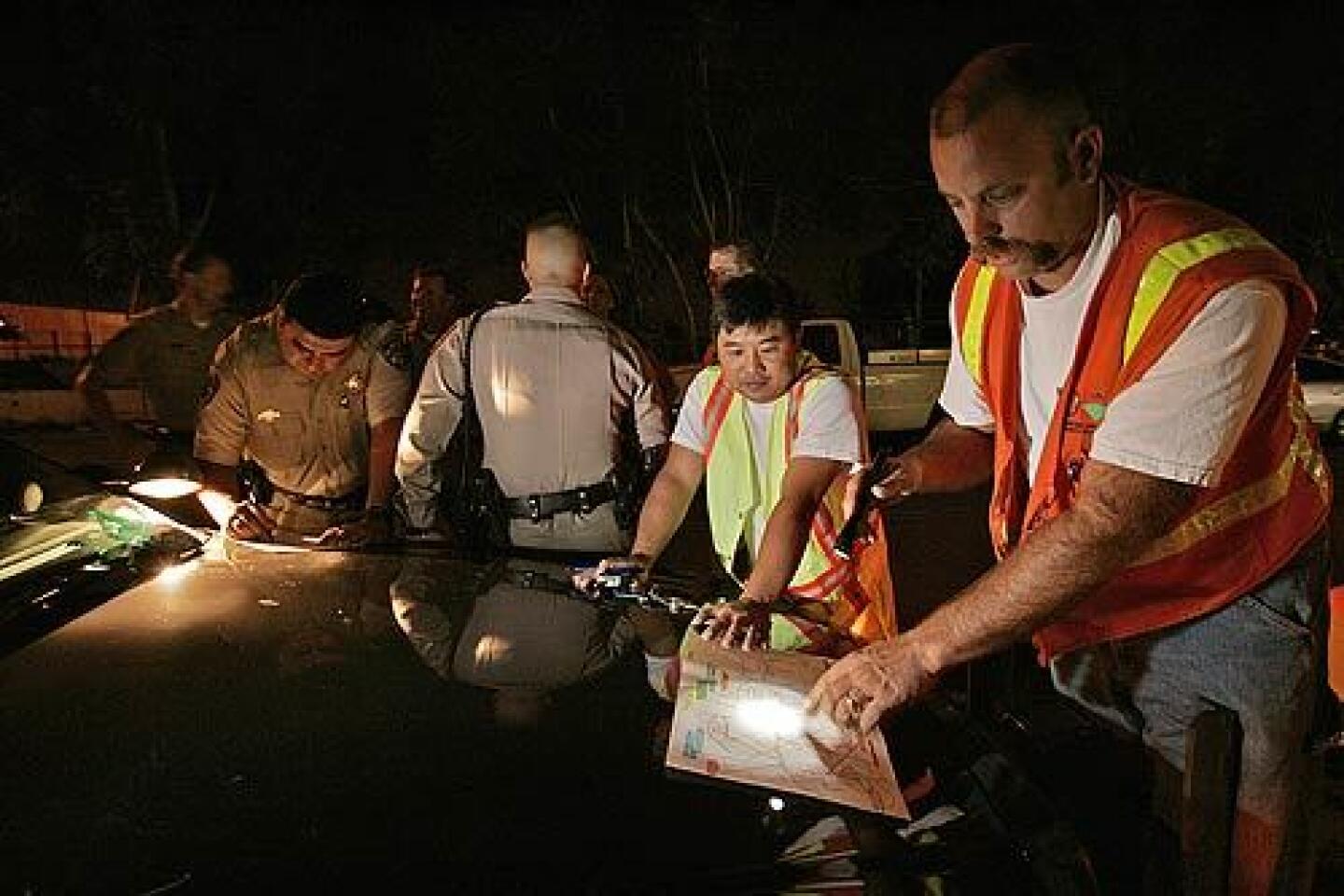

Routing nighttime travelers onto detours is Caltrans inspector Nick Truong’s job. He has worked the 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. shift for the last two years, telling CHP officers when to close a freeway and making sure lane closure signs don’t say “left” instead of “right.” He calls in downed cones and makes sure contractors are doing their assigned work.

Things run pretty smoothly until about 1 or 2 a.m., Truong said. “That’s when you see the crazy stuff,” he said. Teenagers steal detour signs. Pedestrians dash across the freeway on foot. Motorists use closure cones as a driving course. Drunken drivers plow straight into construction zones while workers frantically dart out of the way. Miraculously, no workers have been hurt by errant motorists.

Like Bergevin, the engineer, Truong tries to stay away from the project site -- and avoids freeways altogether -- when he’s off-duty.

“I try not to use the freeway anymore unless I have to,” he said, adding that he’s seen too many bad accidents.

The finish line is a few months away and the work is still challenging, Bergevin said, but the excitement has faded a bit.

“What we’re giving to the public in the end is something you can really see and appreciate, but it’s still been a pain in the butt,” he said. Once construction wraps up on the interchange, he said, “I probably won’t drive through it for a while.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.