Market has been the center of a Hawaiian Gardens neighborhood

Secundino “John” Cabrera has heard it all.

A heavyset man with a shaved head and large glasses, not given to chatter, Cabrera has been the one person in town that folks could talk to when no one else would listen.

Tough finances, lost jobs, births, deaths, the weather, abusive husbands, football, soccer, kids in jail -- you name it, he’s heard it.

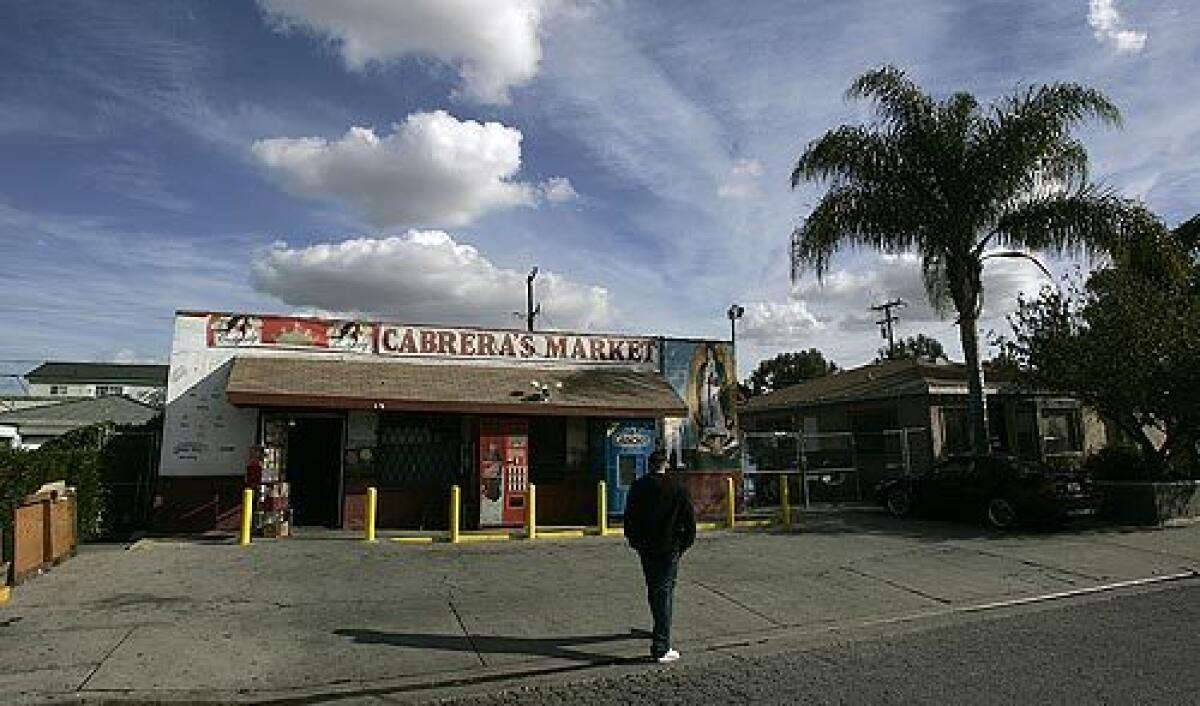

At 64, Cabrera’s life has been the small market that bears his family name in the middle of a block of single-family houses in Hawaiian Gardens.

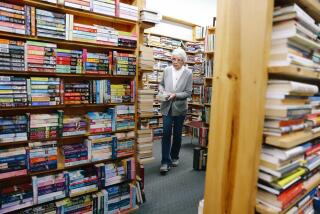

In 1952, his father built Cabrera’s Market. John Cabrera worked there as a kid, and later as a young man back from the Vietnam War. For about the last dozen years, he’s sat on a stool at the market’s shadowy counter, running things virtually alone.

But Cabrera’s health isn’t what it used to be. He’s gained weight. The other day he went for an hour walk in the Cerritos Mall and almost collapsed from fatigue. His sons have other jobs, and he can’t afford to pay anyone minimum wage.

“I just can’t do it no more,” he said, sitting outside the market one day recently.

When Cabrera retires later this month his family will lease out the store.

For many longtime residents, Hawaiian Gardens is their whole world, and Cabrera’s Market its anchor. The store sold candy, cigarettes, cold cuts, milk, soda and beer to generations of families. It cashed their checks as well.

Cabrera’s mother, known to all as Mama Lucy, used to feed the poorest kids at the family house next door.

Jars on the counter contain money collected to help two grieving families pay for funerals. Murals on the walls outside remember people from the neighborhood -- a woman and five grandchildren who died in a house fire and a girl who died of cancer.

“It’s not a store to us. It’s like a home,” said Sylvia Gooden, a customer for more than 40 years who will lease the store. “Everybody’s family here. Everybody’s related in this town.”

Several times, residents have met city and police officials at Cabrera’s instead of City Hall to register their complaints.

But a business like Cabrera’s Market has a cost not measured in dollars and cents.

“Having a mom-and-pop store is like having a jealous wife: You have to be there all the time,” said Mario Montaño, an anthropology professor at Colorado College, who has studied barrio markets in Texas and Colorado. “People come to talk to you. They expect you to be there. You’re the brand, and you have to have good social graces.”

That’s partly why John Cabrera is retiring.

“Some people got problems that are really deep,” he said. “Their kids are looking at 25, 30 years [in prison]. Sometimes you don’t want to listen to it.”

Cabrera’s is one of a collection of markets that sprang up decades ago in the cloistered barrios throughout Southern California when supermarkets were few, and those neighborhoods that had them didn’t welcome Mexicans.

In the 1940s, Margarito Cabrera, a Mexican immigrant, ran a business delivering hay and alfalfa to local dairies. But as more houses sprouted, the dairies moved.

In 1952, Cabrera bought land and built the 1,050-square-foot market. Hawaiian Gardens was mostly pasture then, without sewers or paved streets, and had about 15 houses, owned mostly by whites. Cabrera’s sold about as much rabbit and chicken feed as it did groceries.

The town grew up around Cabrera’s, evolving from an enclave of Southern whites into a Mexican barrio.

The store became the center for news and new ideas. Margarito Cabrera had a petition in the store to push for a tax to build sewers and pave streets.

“ ‘You want to be a gringo,’ they told him,” said Lupe Cabrera, John’s older brother. “They were mad at him because they wanted it to stay the way it was.”

Lupe Cabrera took over the store in 1967 and ran it for two decades. Many customers asked him to be godfather to their sons and daughters. Years later, he contributed to the girls’ quinceañeras -- the traditional Mexican coming-out birthday parties for girls turning 15.

As the store’s owner, he also became the town’s problem-solver. He counseled folks on how to buy real estate. He bailed men out of jail and still wears a ring that was a thank you gift from one of those who benefited from his generosity.

“A couple times I signed my house as collateral,” Lupe Cabrera said, and they always paid up.

In 1972, Lupe was elected Hawaiian Gardens’ first Latino City Councilman.

Meanwhile, another dominant force in town had emerged: the Varrio Hawaiian Gardens street gang.

Successive waves of the gang formed, went wild, then went to prison: the Tinys, Pee-Wees, Enanos (Midgets), Loquitos (Little Crazy Ones).

Intensely territorial, the gang enforced the town’s insularity. A member once told John Cabrera about how he and others had gone to attack a rival barrio less than two miles north. Chased by his rivals, the gang member ran to Pioneer Boulevard, a major thoroughfare, and didn’t know whether Hawaiian Gardens was to the north or south.

“That’s how much they don’t get out,” Cabrera said.

At times, gang members hung out at Cabrera’s.

“You don’t want to play no tough guy with them, because it’s not going to work,” he said. “You respect them; they respect you.”

Indeed, the market has never been robbed -- at least while a Cabrera ran it.

In the 1980s, Korean immigrants found that running Southern California markets and liquor stores in predominantly black and Latino neighborhoods was a path to the American Dream. They took over these businesses, and racial tensions mounted.

Cabrera was among the first in the area to lease his store to Koreans.

Gang members “were robbing these guys right and left, making beer runs on them, defacing the property,” said John Cabrera. “They don’t like outsiders.”

For their part, the Koreans didn’t speak much Spanish or English, removed the popular fresh-meat counter, watched everyone suspiciously and let only a few kids in the market at a time. The Koreans left in 1997 and John Cabrera took over the market again.

When the family decided to lease the market for good this time, gang members told him not to lease to Asians.

Yet the change at Cabrera’s is partly a sign that Hawaiian Gardens’ insularity is fading.

Residents say the town seems moderately more prosperous. Older residents, mostly Mexican Americans, have left, replaced by immigrants from Mexico, without the same ties to the store. New retailers -- cigarette and dollar stores, for example -- have drawn customers with prices that Cabrera’s can’t match.

Added to that is a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department injunction against the Varrio Hawaiian Gardens after a gang member killed Deputy Jerry Ortiz in 2005. The gang’s presence has waned. So has evening traffic at the store, as the department has expanded the injunction to include dozens of Hawaiian Gardens youths, many of whom say they are not gang members.

“Everything came to a stop around here,” Cabrera said.

He’s thinking of removing a Coca-Cola machine outside the store, because profits have dipped significantly with so many youths now under the gang injunction’s curfew.

These days, people who have left town still drive by and take pictures of the market, in the middle of the 22000 block of Seine Avenue. Some stop to talk about the old times when Cabrera’s was about all there was.

But those days are gone.

Sylvia Gooden, a community outreach worker for the city, hopes she can sustain a Hawaiian Gardens institution.

But for John Cabrera, the end of an era can’t come soon enough.

“It’s too hard to cut a profit,” he said. “I’m just worn out.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.