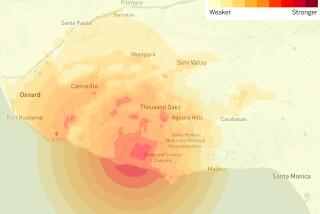

Those who were there recall the Northridge earthquake

The tea had just arrived when “all hell broke loose.” It was as though someone picked up Canter’s Deli and dropped it. Silverware, napkins and hot tea flew off Christopher Ducra’s table and the restaurant went black before yellow emergency lights flickered on.

He and his roommate rushed out of the building and into the middle of the street, hugging as the buildings thundered around them. Fairfax Avenue was still undulating, and a long stretch of swinging power lines cast an eerie blue light.

“Canter’s is older than time. It’s going to crumble,” Ducra recalled thinking. “It was like the end of the damn world.”

In shock and unsure whether it was the end or the start of something bigger, the pair ran back inside to try to pay for their knishes, but the man behind the counter told them to get home. They slowly made the short drive to their apartment through the dark city, with geysers of water shooting into the air from broken hydrants and firetrucks screaming around them.

“It was so violent,” said Ducra, 45, who now lives in New Jersey. “I love Los Angeles, but that was enough.”

::

When his bed dropped and the rumbling started, David Hayter ran for his door. He and his roommate huddled there, gripping each other and the door frame as violent shaking turned to rolling and their North Hollywood apartment seemed to spin in lazy circles as if it were on a turntable. The entertainment center in the living room crashed to the floor, and Hayter said he was sure their loft area would come down as well.

At first, he laughed, then soon feared he would die. The hundreds of aftershocks that came in the following days sent him into survival mode. One of their two cats, Clyde, hid in Hayter’s closet and crawled with his belly to the floor for a week. The other, Bonnie, shook it right off.

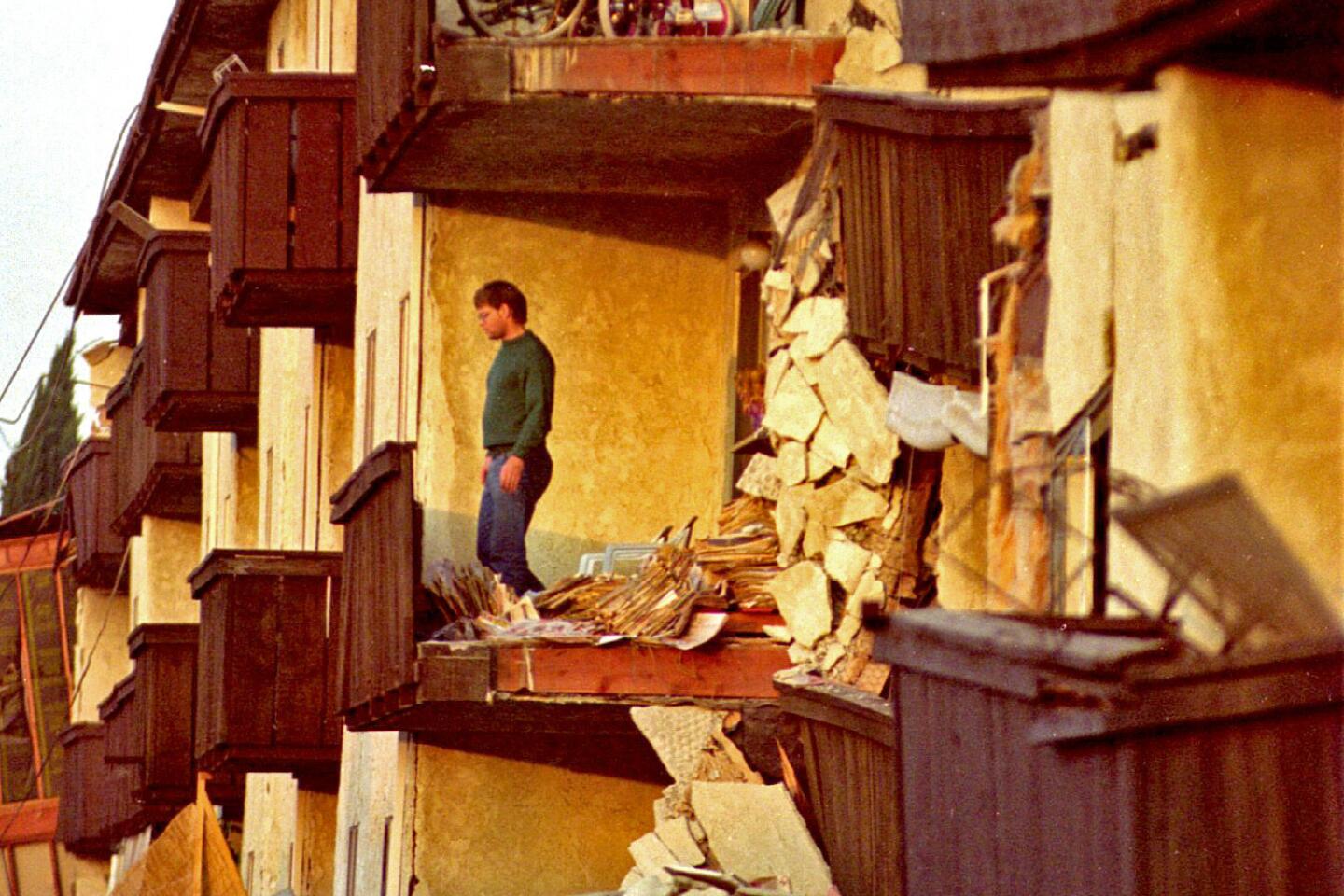

Broken water mains flooded the street, and fire was spitting into the intersection near his apartment, he said. For miles, brick fireplaces lay crumbled and the whole front of one building seemed inches from falling into the street as he drove to check on his girlfriend in her Venice apartment.

“It’s the price you pay for living in this weather, I suppose,” said Hayter, 44, of Sherman Oaks. “I think it just gave me a very healthy respect for nature.”

::

Every January, memories flood 59-year-old Beth Mack when she sees a certain shade of teal in the sky just before dark.

The morning of the Northridge quake, Mack woke to a silent roar — she wore earplugs because her husband snored. It was pitch black outside after the shaking stopped, and she remembers her dazed neighbors, the sound of water rushing from their broken water heaters and the stars, more than she’d ever seen. North of her Sylmar condo, a burning trailer park glowed in the distance. Communication was down, and there was no way to tell how widespread the damage was or who was safe.

But the sky looked incredible.

It was like “somebody there was saying, ‘This is gonna go on, but you’re going to get through this,’ ” she said. “Before, I was waiting to die, and then I went out there.”

::

It took Joy Dockter several hours to get from the Inglewood Red Cross office to the San Fernando Valley on surface streets, transformers exploding into white smoke and flashes of light as the power tried to reroute.

The office was turned upside down, and the clock had stopped at 4:31 a.m. when it was thrown to the floor. She popped the batteries back in and hung it back up.

“It seemed important to get time going again,” she said.

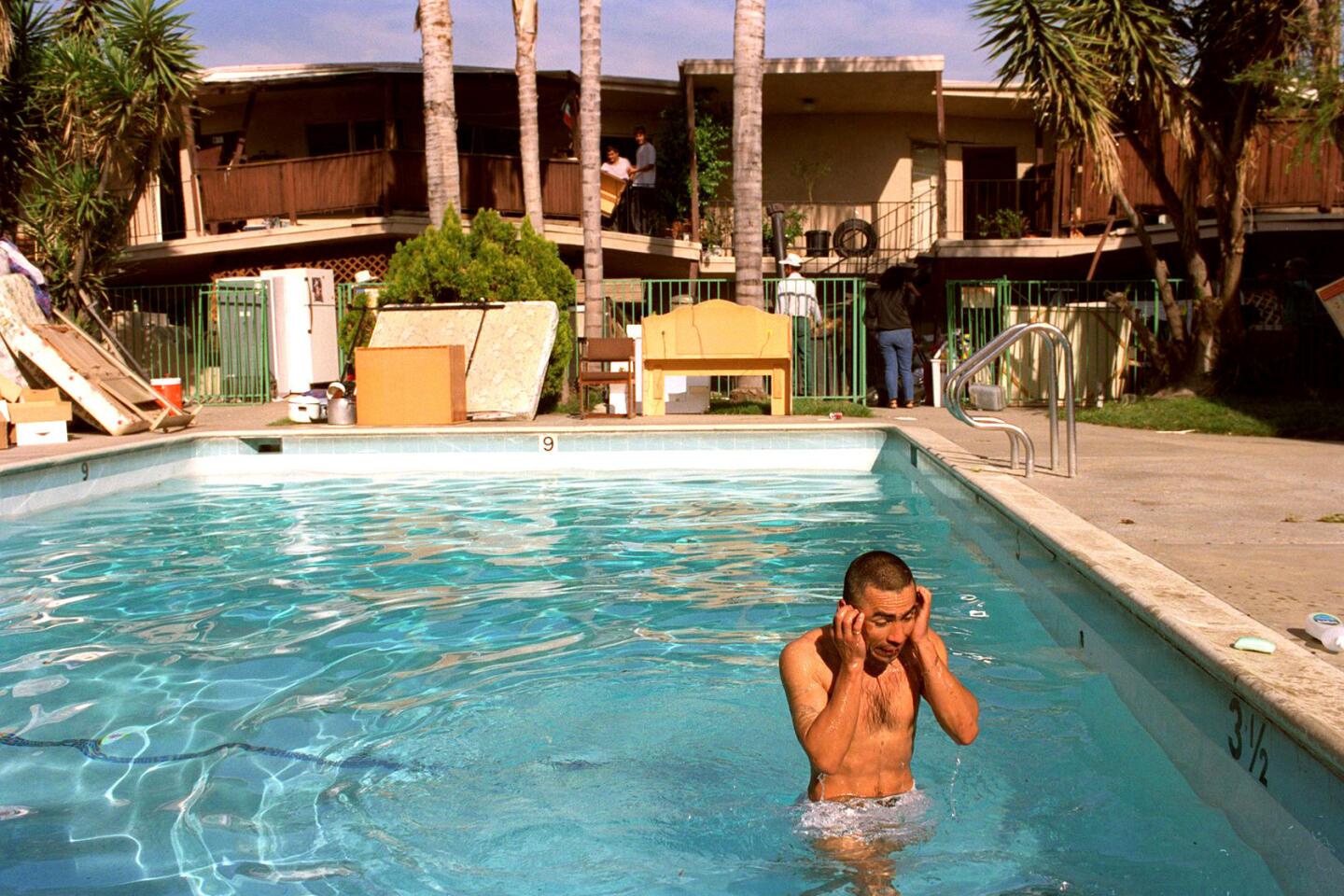

In the 17 days Dockter spent volunteering in the Valley, she watched people move their lives out of an apartment building that had shifted half a foot off its first story while she handed out food from her canteen truck outside Fire Station 88. During the first aftershocks, the light poles on the street whipped through the air like flimsy antennas.

She overheard a firefighter on the phone explaining to his panicked wife why he couldn’t go home and talking her through how to determine whether their house was safe to enter. She ran to get the exhausted emergency responders aspirin for their headaches from a battered liquor store she could smell from a block away.

Days later, people who feared moving back into their homes were still camping in tents made of blankets and tarps in Reseda Park. It wasn’t a typical Red Cross shelter, she said, and the park building was too small to hold them all.

“This is where the people are, so this is where we need to be,” she recalled.

A little girl in dirty clothes dropped a toy through the chain-link fence while waiting in line there for a meal. Dockter picked it up and passed it back to the girl from the other side.

At the time, Dockter lived in Hawthorne — “the safe zone,” she said.

“They were refugees in their own city because they were scared. In their part of the world, buildings were falling down all over the place,” said Dockter, 44, who now lives in Fresno.

::

Steve Ferrera arrived at work at 6 a.m. to see bathrobe-clad out-of-towners scrambling to find rides to the airport in the lobby of what is now the Omni Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. They were done, and they wanted to get out of L.A. The facade of the nearby Biltmore Hotel was a pile of bricks on the sidewalk.

A freelancer who worked at the hotel and needed the money from that shift, he recalls seeing the widespread power outages on his drive from Huntington Beach along the 105 Freeway, a route he decided to take to get a better view and before he had heard about the collapsed overpass. Ferrara, 53, now of Cedarpines Park, was at work for only about half an hour before he was sent home for the day.

::

Keren Interiano can always tell her birthday is coming when she starts hearing about the Northridge earthquake on the news.

Her mother was in the throes of labor when the Corona hospital began shaking that morning. Doctors and nurses ran from the room, and just for a second, Interiano’s father nearly did too. Her parents tell her they held each other, thinking they would die there together and praying nothing would happen to their baby.

When the tremors stopped — in the building, that is — Interiano made her parents wait just a bit longer. “Not to get too graphic, but when the earthquake happened, I was coming out,” she said. “I somehow managed to go back in.”

She was born at 11:45 a.m. Her birthday brings a mix of emotions for her family, Interiano said. Her three older brothers were left home alone when their parents rushed to the hospital.

“Anyone that comes over, they tell that story,” she laughed, saying her mother recalls it as the day they almost died and got the daughter they were hoping for.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.