Piece of San Marino history a victim of the times

Which way to the Michael White Adobe?

“The what?”

“Is that, like, a classroom or something?”

“I have no idea.”

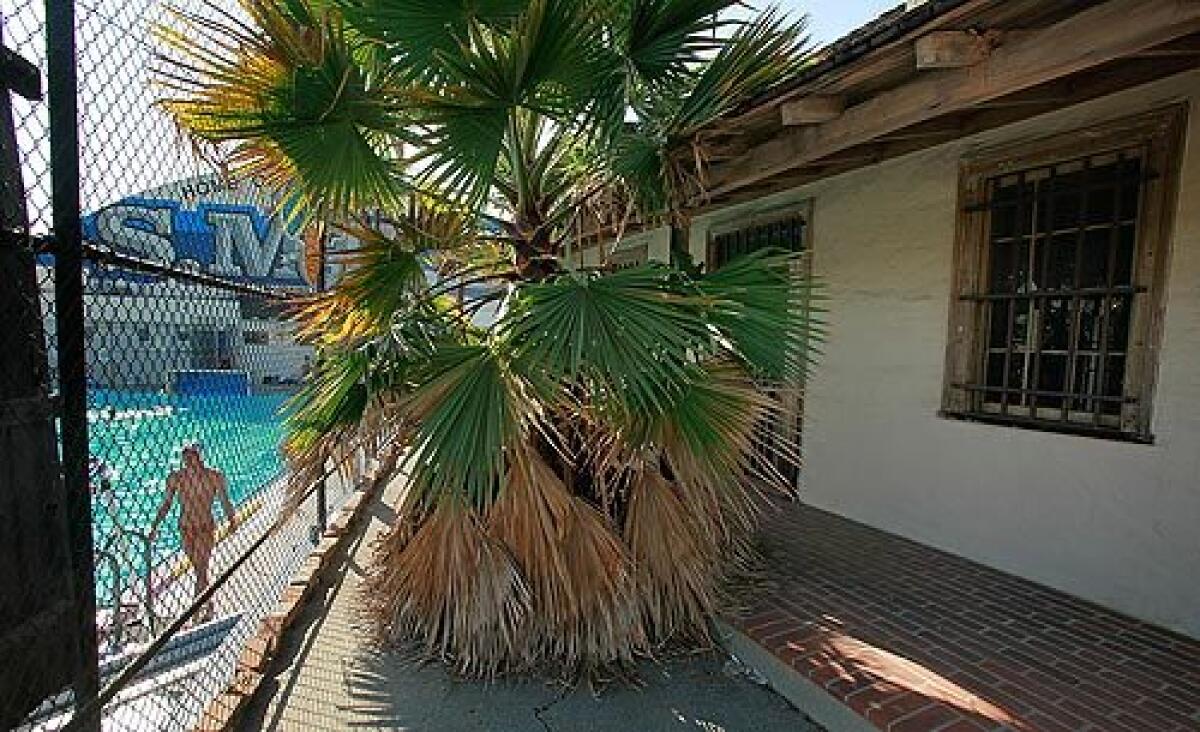

After the final bell at San Marino High School, students making a getaway to parents’ cars or sports practice have little time for a question they don’t understand. But follow the echoes of water splashing and the clink of bats hitting balls, and you’ll discover a tiny house that looks decidedly out of place between the campus pool and baseball diamond.

Here lies the 164-year-old Michael White Adobe, currently on the market for $1.

Unbeknownst to many of the 1,150 students enrolled at San Marino, a national blue ribbon school that has undergone $35 million of renovations in the last 10 years, the adobe is at the center of a debate over old and new.

Local history buffs say the adobe, built a century before the high school was even founded, represents a valuable piece of the city’s narrative and is in need of preservation. Others argue that the building no longer serves a purpose and is a safety hazard in need of removal from an awkward location.

The adobe was constructed in 1845 by Michael White, a European sailor who adopted the name Miguel Blanco and became a Mexican citizen so he could own land in California, which was under Mexican rule at the time. White’s mother-in-law was Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné, who worked at the San Gabriel Mission and owned land that eventually become part of Pasadena, South Pasadena and San Marino.

Now the Michael White Adobe belongs to the San Marino Unified School District, which opened the city’s only high school on the premises in 1955.

Last year, school officials proposed removing the adobe, one of a few dozen remaining in the county, so that the oddly configured L-shaped swimming pool wedged around it could be expanded. But the economic downturn hurt the project’s fundraising efforts, and there were no takers for the adobe when it was put on the market with the caveat that the buyer pay for its removal. It would cost more than $1 million to move the house and roughly the same to make it fit for campus use, environmental documents show.

Knocking down the adobe, the only option covered by the school district’s insurance, comes with a much lower price tag: $176,000. The school board is expected to decide the house’s fate Oct. 27 and is taking public comments through Wednesday.

Once a place where cheerleaders made posters for pep rallies, the fenced-in adobe has been padlocked for decades because its framework is not up to code. Black bars cover the windows and doors, and cobwebs cling to its corners. But those who carry a key to the gate say they’re able to unlock a portal to a compelling past.

“It would be a real shame to destroy a symbol of history that we have here,” said Eugene Dryden, 77, on a sunny Thursday as he pushed open the front door of the adobe.

The former mayor and city councilman has spent his entire life in San Marino, an affluent residential community of 13,000, save the two years he served in the Air Force. A member of the San Marino Historical Society who has donated time and money to the establishment of various city landmarks, Dryden wants the community to understand another relic it has right underneath its nose.

“The value of this is a demonstration to people that there was a guy who came here well before any of this,” he said, motioning to the school grounds, where the sound of Titans engaged in a water polo tournament accented the air.

Over the years, plaster, wood and beige paint have covered the adobe’s thick walls, and a toilet and electricity have been added; but Dryden insists that the structure still represents the work of White. Cool and damp inside, the empty one-bedroom home has rotted away where the original umber-colored sun-dried bricks made of clay and straw peek through the facade.

Dryden is in favor of retrofitting the adobe or moving it to nearby Lacy Park, but the latter may be impossible.

“Our experts are telling us they do not have evidence of a successful move of an adobe,” said San Marino Unified Superintendent Gary Woods. “We’re trying to find a way to protect and preserve as much of the original adobe as possible, but it’s very difficult.”

Woods said that if the adobe is to be made accessible on school grounds, it would have to be encased in a different material and that would further diminish its authenticity.

“The people that have investigated the adobe have found pretty significant traces of termite damage and crumbling of its foundation,” Woods said. “It’s slowly buckling, and at some point part of it will collapse, there’s no doubt about it.”

And after this year’s budget cuts, restoration is not a high priority.

“I’m in favor of people fundraising for its preservation, but as a school board, we can’t budget even a hundred thousand or half a million for the adobe,” said school board member C. Joseph Chang. “We are a small school district, so we don’t have big revenue.”

School board President Jeanie Caldwell said the adobe has been a school board issue since the 1990s. “It’s a dilemma for us,” she said. “Everybody wants it saved but no one wants to save it.”

Although most students have no opinion on the adobe, a few have taken a stance.

“I don’t think most of the students really care that it’s there,” senior Kyle Hon, 17, said. “It’s locked, no one can go through it and it’s in such a weird place. It’s not really publicized at all. It’s more of a hassle because stuff gets stuck in there and baseballs get hit into the house area.”

But freshman Anya Kwan, 13, has toyed with the idea of starting a school preservation club and wishes more of her peers were interested in what’s beyond that black fence.

“People at my age level are more into the new -- what’s hip, not what’s old and what you can learn from,” she said. “It’s sort of sad because we have such a valuable resource on campus and we don’t use it at all.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.