Millions of miles, a hard landing

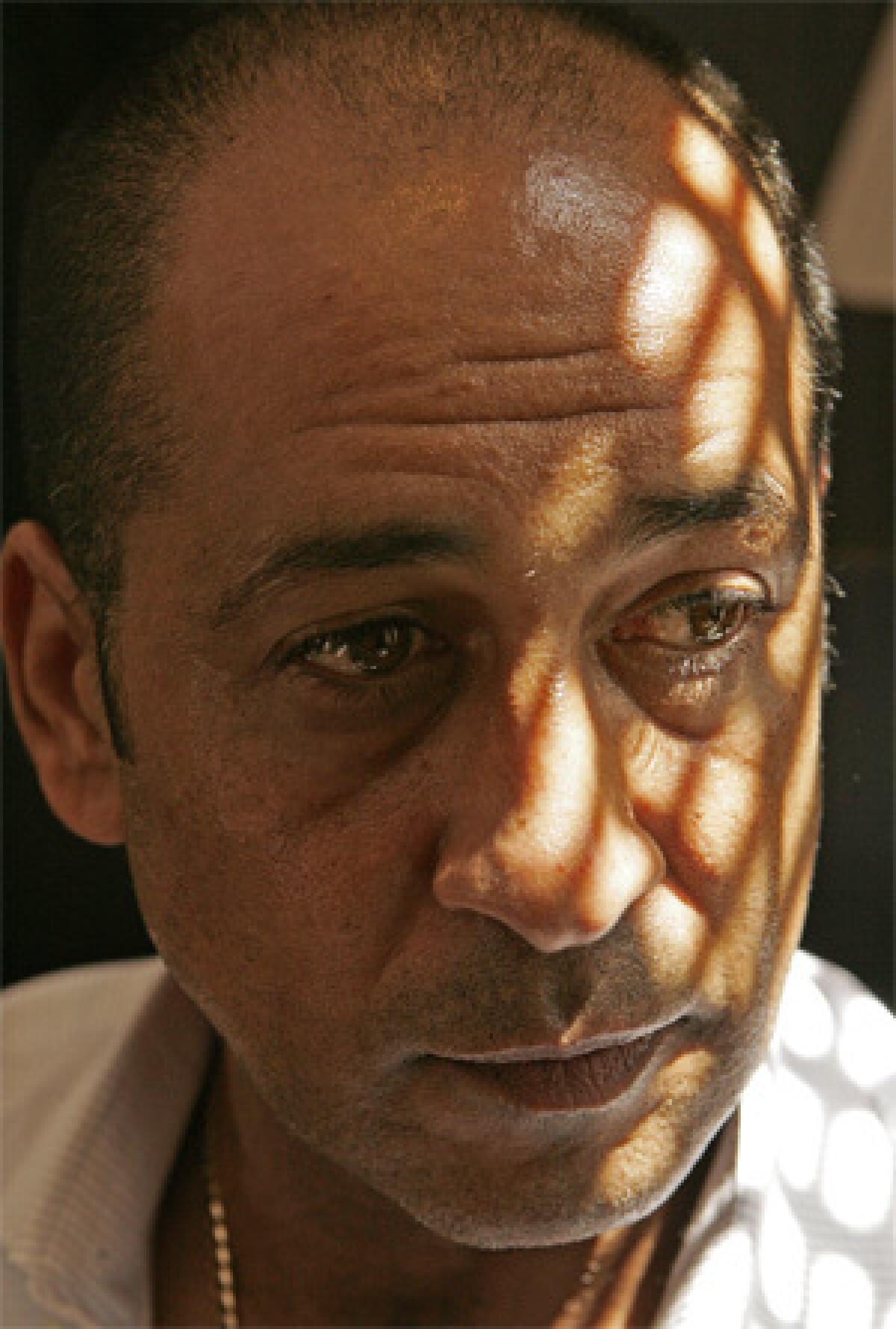

Mohamed Fikry traverses the globe, buying industrial food-processing equipment. In the process, he’s become an American Airlines executive platinum club member, closing in on nearly 5 million miles traveled.

Last July, American Flight 136 from Los Angeles International Airport to London’s Heathrow Airport began as just another trip for Fikry.

The 53-year-old Pasadena resident boarded the plane and changed from business attire to a sweat suit in one of the lavatories before settling into Seat 13J at the back of business class.

There, he ate a few bites of a Bristol Farms ham sandwich and cookies, took a sleeping pill and washed it down with two glasses of wine.

Before dozing off, he spoke briefly with a flight attendant.

“I saw you on the tram before,” she told Fikry.

“It’s possible,” he replied, thinking the two might have crossed paths. He briefly wondered what she meant by the “tram.” He routinely rides shuttle buses to and from parking garages, but “tram” is a word usually applied to employee buses.

A few minutes later, when the woman sitting next to him went to the restroom, the attendant returned and took the empty seat.

Could she trouble him for one of his business cards? “Sure,” he said. The plane took off as scheduled. Minutes later, he was asleep.

Fikry awoke to the Boeing 777 descending. His watch read 11 p.m., just 4 1/2 hours into the flight.

“You couldn’t make it to London on the Concorde in that time,” he recalled thinking.

The woman next to him said they were making an emergency landing because the plane was low on fuel.

But on the ground, there was no sign of emergency personnel or equipment to greet a stricken plane.

The pilot announced to the more than 200 passengers that they were at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City and to stay in their seats because of an unspecified emergency.

A dozen law enforcement officers boarded the plane. They stopped at Fikry’s seat.

“Get all of your belongings, we are unloading your luggage, get off the plane,” one said.

“What would you say to the officers?” Fikry said later. “Of course, you are going to say yes.”

What happened next would become a lead story on TV newscasts around the country.

The reports said the flight had been diverted because a passenger was able to circumvent security screening in Los Angeles.

The incident came days after an intelligence report had warned that Al Qaeda had reconstituted and represented as great a danger to the United States as any since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Hours after Fikry was detained in New York, U.S. Homeland Security Chief Michael Chertoff went on the “Today” show to talk about the case, saying a man was in custody after he boarded a plane posing as an American Airlines employee.

The “person of interest” was Fikry.

Despite all the time away from home and the occasional hassles, Fikry enjoyed his life as a globe-trotting businessman.

A native of Cairo, Fikry runs an international trading company that specializes in buying and trading food-processing machinery, a job that regularly takes him to Asia, Central America, Europe and the Middle East.

He liked the bustle of airports, where he could people-watch and pick up casual conversations with fellow passengers.

Flying also was a pleasure, as personal as family.

“It was always a greeting by my surname, ‘Mr. Fikry,’ ” he said. “They knew that I didn’t eat the airline food. They joked I couldn’t handle gourmet.”

Over the years, he had become friendly with some of the American Airlines workers who served him on various flights.

“People knew I had two homes, in the L.A. area and Egypt,” he said. “They knew about my family. I knew about their families or significant others. It was very, very personal.”

But the 9/11 attacks -- and the increased airport security that followed -- dramatically changed his travel routine.

Ten days after the attacks, Fikry was returning from Chicago when a woman mistook sketches of a meat grinder he was reviewing as notes detailing aircraft emergency exits.

The FBI interviewed him at length before clearing him.

Whenever he flew, he could count on disapproving looks from fellow business-class passengers and extra time in the security line as officers searched his belongings.

Once onboard, Fikry decided not to use the restroom near the cockpit for fear it might arouse suspicion.

He even shortened his first name to Mo after finding that his given name was putting too many people off.

“I did not commit a crime for being Mohamed,” he said. “But I have to be Mo. That says it all. It’s the price of belonging to your own heritage.”

Over the last two years, the situation at airports began to improve for Fikry. He sought refuge at American Airlines’ elite Admiral’s Club, a private lounge for high-profile fliers. He once again felt embraced by the familiar faces of his airport connections.

Then came the flight from LAX to London.

With federal agents hovering over him and his plane grounded at JFK, Fikry walked past his fellow passengers, who stared as he exited the aircraft. He said he felt ashamed.

Still groggy from the sleeping pill, Fikry was held in the jetway for about an hour. The officers, who included FBI agents and New York police detectives, took his passport before questioning him about his travel plans and frequent flights.

“They mentioned Cairo several times and focused on my travels to the Middle East,” Fikry said. “I told them it was because I have family and conduct business there.”

Agents told him that a flight attendant claimed that she saw him on a tram for American Airlines employees. She feared that he had somehow circumvented security to get on the flight, they told him.

He asked to speak with the attendant.

A few minutes later, she came into the jetway.

“Did you, at any time during the bus journey, have a conversation with me? Did we exchange eye contact? Or did I make any gesture you remember?” he asked.

She replied no, he said.

After boarding, “Didn’t you say I was a good passenger to have on a flight?” Fikry asked her.

She answered “indeed you were,” then left the jetway. The agents escorted Fikry to the seating area next to the gate.

Still groggy, he lay down -- head against his duffel bag -- and again fell asleep.

He awoke two hours later. It was about 4 a.m. He was surrounded by agents.

“They were looking at me as if I was the son of Osama bin Laden,” Fikry said. “It was a horrible and humiliating feeling.”

He received police escorts to the lavatory. One watched the door. Another stood over him.

Over the next few hours, agents checked out Fikry’s alibis. They learned that he had in fact parked in the regular lot, gotten his ticket at the counter, gone through security and even spent some time at American’s Admiral’s Club before boarding the plane.

By noon, agents told him he was free to go. Slowly the story began to spread, with officials telling the media that the passenger had indeed gone through regular security channels.

Even though he felt a measure of vindication, Fikry said the experience left him dazed, disappointed -- and incredulous about how the word of one flight attendant could count against him with no supporting evidence.

“It was purely based on appearance, heritage and my name,” he said.

FBI and American Airlines officials deny this, saying their people handled the incident properly.

FBI spokeswoman Laura Eimiller said that although most reports of suspicious activity are “resolved with no charges brought,” it was the bureau’s “responsibility to investigate reports by citizens of suspicious activity . . . particularly in a period of heightened awareness when the FBI has called for a vigilant public.”

Through a spokesman, American Airlines said it had investigated what happened and found “no reason to think that our flight attendant was motivated by any improper motive or that her actions resulted from anything other than an honest case of mistaken identity.” American declined to make the attendant available for an interview.

The spokesman, Tim Smith, said the carrier had “attempted to address the inconvenience Mr. Fikry experienced by arranging, at our expense, for upgraded travel on American for the balance of his itinerary to Europe and back to California.”

Fikry continued to travel on American Airlines, including flights to Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama, the Philippines, the Netherlands, Italy and Egypt. But he was a different traveler. He was much more cautious about avoiding misunderstandings. He stopped striking up conversations with strangers in the next seat and bringing his laptop on the plane. Even in the Admiral’s Club, he tried to keep his head down and mind his own business.

On Sept. 26, he boarded Flight 136 from Los Angeles to London -- the same flight on which he was detained in July.

He even sat in the same seat.

He was relieved that the flight went smoothly. But he was also disappointed that while the crew seemed at ease with him, they chose not to apologize for the way he had been treated.

He brooded. In December, he asked his attorney to send a letter to American demanding an apology, further compensation for the lost time waiting at JFK and a discussion of ways to prevent others from being treated the same way.

As he waited for a response, he continued to fly American Airlines. By January, he was only 50,000 miles shy of amassing 5 million. Reaching the milestone was important to him -- bragging rights for a man who had spent a large chunk of his life in the air. Though there is no specific reward for accruing 5 million miles, under American’s rules, passengers with Fikry’s mileage level are eligible for automatic upgrades and other perks.

A January trip from Tokyo to Los Angeles would close the gap further.

Fikry settled into his seat in business class. Then his eyes met those of the flight attendant who had accused him back in July. She was serving passengers in his part of the cabin.

He noticed other flight attendants looking in his direction, appearing to point and whisper.

“I felt like a caged animal at the zoo,” he said. “[I was] the guy who grounded Flight 136. I felt it was like a parade, and everybody was looking at the king clown.”

Because of their history, Fikry requested that the flight attendant be moved out of first class. When he got no response from an attendant whom he knew, he moved himself into coach to avoid being served by his accuser.

“It was as if I was the profile and not the person,” he said. “It was degrading, and if I was Mr. Smith and not Mr. Fikry, it wouldn’t have happened.”

Smith, the American Airlines spokesman, declined to discuss the Tokyo incident, adding that the airline believed Fikry was satisfied with its response to his complaints. As for Fikry’s December letter, Smith said the airline strongly disagrees that Fikry was in any way discriminated against.

When Fikry got home, he decided to stop flying American, resigned to the fact that he’d never get to 5 million miles.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.