Celebrating a shared history

On an uninviting swatch of arid desert, marked by sagebrush and mesquite trees just east of the California border, the winds of war blew together the fates of two beleaguered peoples.

In a now familiar tale, 120,000 Japanese Americans were removed from the West Coast and relocated to internment camps after Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent U.S. entry into World War II. But in a little known piece of that history, the U.S. government sent nearly 20,000 of them to three camps on a Colorado River Indian Tribe reservation at Poston with an explicit plan to use Japanese Americans -- most of them Californians skilled in farming -- to help develop tribal lands for later Indian use.

FOR THE RECORD:

Relocation camp: An article in Tuesday’s California section about Japanese American internees sent to Poston, Ariz., during World War II misspelled Mary Higashi’s name as Hayashi. —

Under the plan, the Japanese Americans helped clear lands and build irrigation systems, started farms and built schools from handmade adobe bricks. Their work in developing a reservation that previously had no electricity, running water or modern homes -- many families lived in mud huts -- laid the foundation for the tribe to jump-start its standard of living and thrive financially, said Michael Tsosie, director of the tribal museum.

Now, 66 years ago today after then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the relocation, the two peoples are deepening their shared bonds.

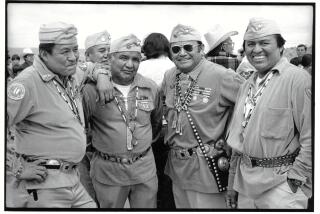

Last week, Native Americans and two dozen former Japanese American internees gathered in Poston to memorialize their experiences and view a new documentary about it, “Passing Poston,” by New York filmmakers Joe Fox and James Nubile. They also discussed plans to restore some of the barracks, seek national historical landmark status for the site and build a museum about their shared history.

“The basis of our present-day wealth is the result of the activities during the war years by the Japanese,” Tsosie said. “Maybe if they knew that all of their suffering and hard work did make a remarkable difference in the lives of so many tribal people, it might bring them some peace.”

The lasting effect of their fateful desert encounter remained largely hidden for decades by elders in both communities who declined to talk much about it, both sides say. In 2000, however, Berkeley artist and researcher Ruth Okimoto, 71, began researching Poston in a personal quest to understand the experience that had torn her life apart.

Okimoto, a Tokyo native brought to San Diego as an infant by her Christian missionary parents in 1937, was only 6 when she arrived at Poston in 1942. Her memories of the time are sketchy: a German neighbor making her family split pea soup before soldiers with rifles and bayonets took them away. Shame at having to share latrines and showers with so many strangers. Hunting for petrified wood and scorpions in the vast, forbidding landscape.

Other, older former internees who journeyed to Poston last week shared their memories. Kiyo Sato, a Sacramento retired school nurse who was 19 at the time, remembered fainting from the blistering desert heat, which climbed as high as 125 degrees.

San Pedro resident Mary Hayashi, also 19 at the time, remembered arriving at the dust-filled barracks bereft of any furniture but an oil stove. She collapsed to the floor in tears.

Okimoto was chased and spit on, rocks heaved at her by schoolmates when she returned to her San Diego elementary school in 1945. As she became an artist in the 1970s, dark and troubling images began to surface in her work -- a two-faced portrait of herself, the American flag covering her child’s eyes and adult mouth. That began her journey of self-discovery that, in 2000, led back to Poston.

“I needed to go deep into my subconscious to see who I am,” Okimoto said.

For their part, the tribal people had no say over the mass encroachment on their land, museum director Tsosie said. Only when government trucks began rolling in to build the barracks did leaders begin to ask questions.

“The other Indians didn’t like them coming in,” recalled Gertrude B. Van Fleet, 83, who used to visit the camps with her father, the Mohave tribe’s first Presbyterian preacher who ministered to the internees. “They were worried because people were always coming in to take land from the Indians. Some spoke out real hard. Some wanted to chase them out.”

But the Indians were told: “It’s part of the war effort. Don’t ask questions. Do your patriotic duty and accept it,” Tsosie said.

The Japanese American population, peaking at 19,000 scattered over three camps, dwarfed the 1,200 Mohave and Chemehuevi Indians living on the reservation at the time. But the encounters were limited, both sides say. An armed guard was posted at a canal that divided the populated upper reservation with the lower reservation where the internment camps were placed. And the Indians were told not to mingle with them.

Still, Tsosie said his own family remembered renting them horses and trading fish they caught from the nearby canals and Colorado River for camp provisions of sugar and flour. There were basketball games between Japanese Americans in Poston and American Indians from a nearby high school in Parker.

Dennis Patch, who heads the tribal education department, said many Indians felt empathy for the Japanese Americans. The tribes themselves had been herded up and forced onto the Colorado River Indian Tribe reservation when it was established in 1865 to open land for white settlers, he said.

“They saw people captured and put some place they didn’t want to be, and they understood that,” Patch said.

At least some tribal students were aware that the Japanese Americans had begun to transform the barren reservation. In one school essay, a student wrote that the bountiful fruits and vegetables they grew -- cantaloupe, lettuce, spinach and the like -- “were as good as can be grown anyplace. They have shown that this valley has great possibilities as a vegetable growing center,” according to documents unearthed by Okimoto.

What the Berkeley researcher would discover was that the U.S. government had deliberately selected Japanese Americans with farming experience from California Central Valley towns like Sacramento, Bakersfield and elsewhere, to help develop the reservation’s agricultural potential, Okimoto said. Researching documents in the National Archives, along with Colorado River Indian tribal archives and other sources, Okimoto discovered the then-named Office of Indian Affairs partnered with the War Relocation Authority to develop an internee labor plan..

Commissioner John Collier of the Indian Affairs office had long sought federal funds to bring irrigation and other projects to the reservation to make it self-sufficient so the government could bring in other tribes. World War II finally gave him an opening to offer the land up as an internment camp in exchange for permanent infrastructure improvements.

Among other documents, Okimoto discovered an April 1942 letter from William Zimmerman, the Indian office’s assistant commissioner, to the House of Representatives that outlined the plan. Zimmerman proposed using the Japanese to transform 10,000 acres -- clearing it and constructing canals, drainage ditches and flood levees -- and then cultivate it “as rapidly as possible.”

The projects were never fully completed, but the reservation ended up with new roads, electricity, irrigation systems, housing and the like.

Many tribal members were able to receive parts of the old barracks as their first modern homes, including Van Fleet. Before the Japanese came, she recalled, she lived in a mud hut and used kerosene lamps for lighting. Other wartime buildings were maintained and used for such purposes as tribal schools, youth centers and alcohol-rehabilitation programs. The buildings, now shuttered, were visited last week by several of the former internees and form the heart of the application for national historical landmark status.

Overall, the improvements gave the Colorado River Indians a “step ahead” on postwar progress compared to other tribes, Patch said.

They began leasing land for commercial agriculture and started their own farming enterprises as well. The tribal budget has grown from an annual $7,000 in 1952 to $28 million today.

“Much of this would not have happened without the Japanese laying the groundwork,” Tsosie said.

Last week, on a wind-swept patch of desert, where Japanese Americans erected a stone memorial monument in 1992, Tsosie delivered his thanks to several former internees. Tribal youth performed traditional Indian songs and dances. A Japanese Buddhist priest burned incense and said prayers.

For Okimoto, the tribal progress has allowed her to find meaning in her personal saga of suffering.

“Here were two minority groups struggling,” she said. “If what we did helped them, then I guess it was worth the suffering the Japanese endured during the war.”

teresa.watanabe

@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.