From Rwanda to Redlands

As a boy, Patrick Manyika looked up and watched packages of corn and canned fish fall from the sky.

An airplane streamed overhead, dropping supplies to the hundreds of refugees living in isolation in the rolling hills and forests of northeast Rwanda.

The relief packages read “USAID” — it was the first word he would learn to read.

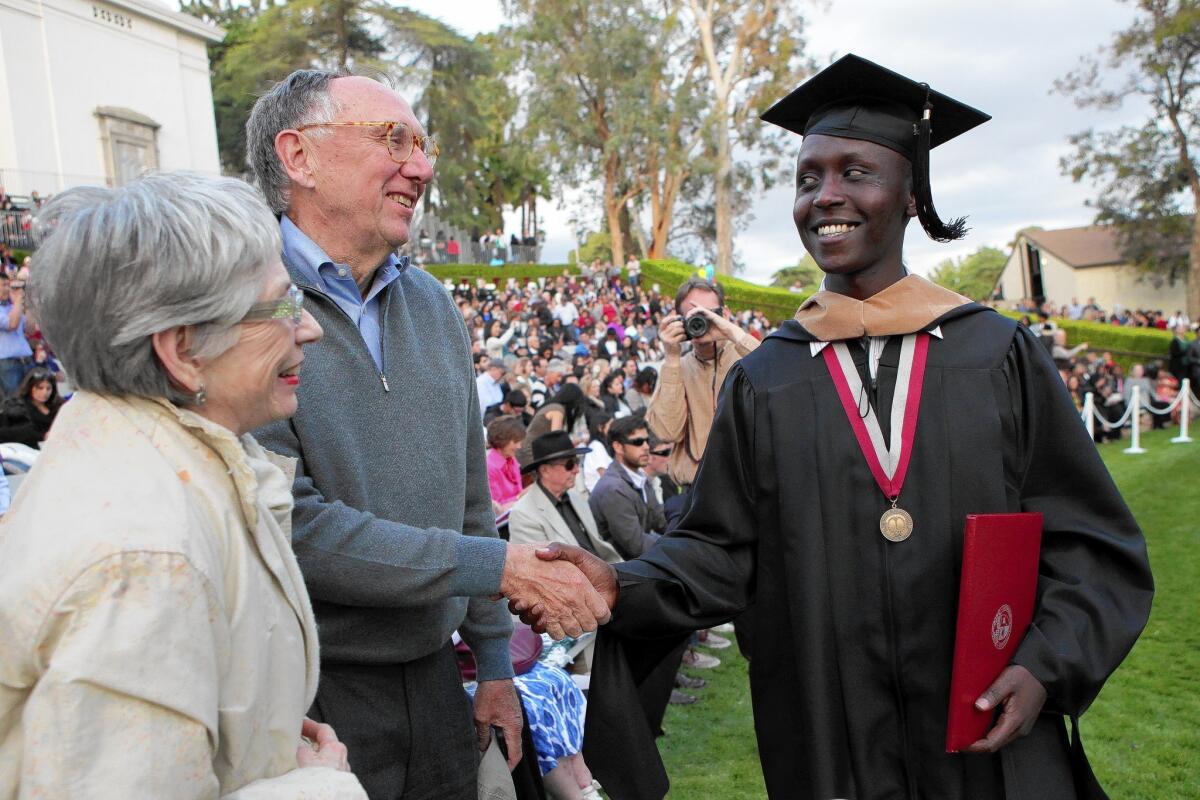

Manyika lived as a child in exile on the land of a national park, survived the Rwandan genocide as a teenager and eventually made his way to a private university in Southern California. He earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Redlands, and on Saturday walked across the stage there with a master’s degree in business administration.

No family members attended his graduation, but Manyika, 33, said he had been aided by friends he met here.

“I am nothing by myself,” he said. “It is all because of everyone who helped me.”

His education was funded by a family he befriended on his first trip to the United States, and he credited his classmates and professors with easing his life once he settled here.

He struggled to adapt to his new home. Even though he speaks six languages, his English was spotty. Freeways were confounding. He once tried walking to campus on Interstate 10. Someone later told him to not do that. “I figured something was fishy,” he said.

He wasn’t sure how to turn on the air conditioning in his apartment and became dehydrated. Instead of water, Manyika drank soda until a friend advised him against it. In his country, direct eye contact and a firm handshake were insults.

“Everything was opposite, upside down,” he said.

A few months after arriving he wanted to return home. He missed his family.

“But I had to do a cost-benefit analysis,” he said. “What I’m gaining here is more than what I am losing.”

Manyika was born in a refugee camp in Uganda after his family fled from unrest in Rwanda. Soon they were forced back. With nowhere to go, they lived in Akagera National Park, where he would chase zebras for fun and learned to build traps out of trees to catch food.

In 1987, Manyika and his mother and younger sister went to Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, hiding their identities as Tutsis so the children could go to school.

In 1994, the deaths of the Rwandan and Burundian presidents, both Hutus, sparked the killings of more than 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus by Hutu extremists.

At one point, Manyika remembers opening his front door and a neighbor, wielding a machete, vowed to kill him and his family.

The family fled to a soccer stadium controlled by United Nations forces, where they lived for weeks while war raged around them. The stadium was constantly under attack. His immediate family survived, but he estimates that more than 50 other relatives and friends were killed.

“When I came to see my other family members, they were all gone,” he said.

Manyika would continue his studies, attending a university in Rwanda before deciding to delay his education to work. He was hired by Partners in Health, an organization that seeks to implement a stable healthcare system in the country. He loved the job but realized he lacked the business expertise to advance his career.

The group sent him on a trip to the U.S., where he visited the Redlands campus. A San Francisco Bay Area family he met offered to fund his studies if he chose to remain in the U.S. He applied to Redlands, was accepted and began in 2009.

At school, Manyika seemed slightly out of place as an undergraduate, according to some of his classmates.

“He seemed a little standoffish,” said Mark Hensley Jr., who graduated with Manyika in 2012. “It seems like he almost felt intimidated.”

At first, Hensley wasn’t even sure whether Manyika was a foreign student because he said so little about himself. But about halfway through the year, Manyika started to feel more at home and became one of the group’s most outspoken students. “He was the guy in every single group who would take a leadership role,” Hensley said.

Manyika acquired a car and quickly put on weight on his tall frame because he no longer walked everywhere. His grades improved from a 2.2 grade point average to 3.7. He made friends and attended parties. A group in town, the International Friendship Connection, held dinners and organized trips to help in his transition.

Roland Sprague, a professor in the University of Redlands graduate business program, noticed that Manyika was different from other students. “He didn’t use his cellphone, he wasn’t texting,” Sprague said. “It was obvious from the beginning he was paying attention.”

Stuart Noble-Goodman, dean of the university’s business school, said Manyika’s resilience had impressed faculty and other students.

“We’re awfully proud of him,” he said. “He’s survived a lot and he has thrived.”

Manyika will return to school, pursuing a master’s degree in geographic information systems, to add technical skills to his managerial expertise. Those skills are scarce at home, he said, and he hopes to work with a nonprofit. One day he would like to start his own nonprofit, aimed at increasing access to clean water and health resources in Africa.

“I want to do something that makes change, that helps my people,” he said. “Before I didn’t know enough to do it on my own — now I can.”

Times staff writer Jason Song contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.