Northern California counties revive an old idea for a breakaway state

YREKA, Calif. — Farmers, ranchers and onetime loggers were among those who packed a church community room here in August to listen to a former state lawmaker convey his vision of a cleaved — and more governable — California.

The theme was familiar, the resonance deep for those convinced that relentless regulation is strangling the economy of this northern border county. But this time, a tall man sporting a baseball cap stood up with a challenge.

“Are we just going to go have an ice cream and complain?” said Mark Baird, a pilot of 747 cargo planes who with his wife runs a cattle ranch and the local radio station. “Or are we going to do something about it?”

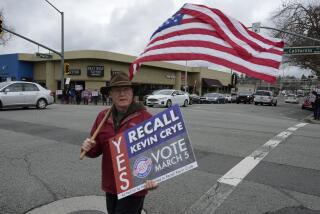

PHOTOS: Pondering a separate state

Within two weeks, Baird had crafted a declaration in support of the breakaway State of Jefferson and placed it on the Siskiyou County Board of Supervisors agenda. It was approved a week later on a 4-1 vote.

And with that, a movement that has waxed and waned for 150 years was born again.

Neighboring Modoc County’s supervisors soon clamored for a similar declaration, and also voted “yea”; the Tehama County board agreed to put the matter to voters; and organizing committees sprang up in seven other counties.

The State of Jefferson flag — which dates to a 1941 effort — is now flown from the Nevada border west to the Pacific Ocean and as far south as Yuba City. (It features a gold pan with two X’s, for the double-crossing purportedly dealt to residents of Northern California and southern Oregon by their respective seats of state government.)

Baird rattles off the movement’s rationale: An independent state would deliver local control to a region whose residents have long chafed under Sacramento’s rules, feel alienated from urban culture and believe in greater push-back against an overreaching federal government.

Most notably, supporters say, it would provide stronger representation to a swath of counties so sparsely populated that their collective voice is now lost in the breathtaking landscape of mountains, rivers and alfalfa-dotted valleys.

“All we want is the right to determine our own future,” Baird said. “This is for our children, and their children.”

Majority votes are required in the state Legislature and U.S. Congress for separation to occur. The last state to do so was West Virginia — in 1863 — and dozens of regions across the U.S. have since seen their efforts fizzle, most recently last month when just five of 11 Colorado counties voted to form an independent state.

But in the northern rural counties of California, the idea has widespread backing from frustrated residents craving economic opportunity and control.

“We are staking our futures on our ability to live and thrive in this area,” said Kayla Nicole Brown of Redding, a 23-year-old student of early American history who has become a leader in Shasta County’s movement for the sake of her 10-month-old son, Hunter. “And if we can’t, we have to leave.”

::

In Yreka’s Palace Barber Shop, a State of Jefferson flag hangs near heads of bear and elk, and a tiny stuffed Bigfoot doubles as cheerleader, a sign proclaiming Jefferson “the 51st State” in its hand.

Owner John Lisle, 55, chats easily about California’s “growing urban/rural divide.” As he rattled off obstacles to those “making a living off the environment” on a recent evening, a young customer weighed in.

“I think we should do it,” blurted Isaiah Solus, 14, a descendant of Siskiyou County pioneers from Portugal. “We’re a whole different part of the state. We need our own water, we need our own rules.... We need a whole different set of things than the city people.”

The menu of grievances includes a proposal to remove Klamath River dams, a crackdown on gold dredging and a fire prevention fee for rural areas that has been challenged in the courts as a tax.

They are recited in the remotest pockets, where the movement’s talking points have spread thanks to Facebook and websites devoted to the cause.

The Scott Valley stretches green and languorous in the shadow of the pristine Marble Mountains. Punky Hayden, 72, was born here the year the movement first sparked, and his father, a county supervisor, spoke of it often.

“We’re governed by Los Angeles and San Francisco,” the former logger said. “We live by their rules, and we don’t like living by their rules.”

Still, Hayden believes the State of Jefferson will remain a state of mind. “I’m an optimist,” he said, “but I’m not that much of an optimist.”

Baird and others doing the legwork have no time for such defeatist talk. Between now and mid-February, town hall meetings are scheduled in Butte, Glenn, Sutter and Del Norte counties.

Del Norte organizer Aaron Funk is stepping down from nearly half a dozen local boards to focus full time on the withdrawal movement.

The vote at one recent meeting of core volunteers: to study up on precedent and begin plotting logistics.

“If we can’t convince our own board of supervisors, we’ll never be able to convince the state Senate and Assembly,” said Funk, 72.

::

Baird prefers “separation” to “secession,” noting that the U.S. Constitution spells out the process.

A Los Angeles assemblyman in 1859 pushed for a split at the Tehachapi Mountains. California’s Senate and Assembly voted approval and a federal bill was in the works when the Civil War intervened.

In his recent book “The Elusive State of Jefferson,” Oregon journalist Peter Laufer recounts the 1941 effort that gave the current movement its name and logo. A citizens committee regularly stopped traffic near the Oregon border to distribute political circulars, and the would-be first governor was waiting in the wings.

But the bombing of Pearl Harbor turned attention elsewhere. And in the decades that followed, grabbing Sacramento’s attention became more difficult still.

As in many states, California’s upper legislative house had offered geographic representation. But a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1964 put a stop to that. Reynolds vs. Sims involved Alabama’s system, which had led to disenfranchisement of minority urban voters.

“Legislators represent people, not trees or acres,” wrote Chief Justice Earl Warren, relying on the principle of one person, one vote.

For better or worse, the ruling set the stage for dwindling rural representation.

“If our state assemblyman and senator both went to Hawaii for a year,” Funk said, “it wouldn’t make a difference.”

In 1993, north state Assemblyman Stan Statham, a Republican, made another push for a divided California. But despite ballot approval in 27 counties and help from then-speaker Willie Brown, who quipped that he’d rather have his enemies split among two states, the campaign went nowhere.

Statham, still pushing for division, spoke to the packed Yreka church hall that August evening. His upcoming book, titled “Restore California,” includes a preface from Brown.

Late this month another voice joined the mix: Citing the State of Jefferson movement as inspiration, Silicon Valley venture capitalist Tim Draper launched a state ballot initiative to carve up California — into six states.

Political analysts say congressional Democrats would never go for it. But an elated Baird is working to arrange a meeting with Draper.

::

The debate over the State of Jefferson often boils down to a balance sheet. Laufer’s tally from the state Department of Finance concluded that California’s four northernmost counties take in $20 million or so more per year from Sacramento than they provide.

At a recent Board of Supervisors forum, Tehama County Chief Administrator Bill Goodwin estimated a loss of $5 million in public works funding annually and a 75% drop in education funding were the county to join in, and he hadn’t begun to calculate the impact on health and social service programs.

Then there are logistics: What to do about the state prison in Crescent City? Who gets the Caltrans equipment left behind? And what of steep out-of-state tuition Jeffersonians would be forced to pay in California’s higher education system?

But Baird and others are convinced that a “more favorable regulatory environment” could help them boost a region with some of California’s highest poverty and unemployment rates.

They expect they might be ignored in Sacramento. In that event, they plan to take their fight to federal court to try to poke holes in Reynolds vs. Sims.

James Huffman, emeritus dean at Oregon’s Lewis and Clark Law School, earlier this year penned an article in a Hoover Institution journal that explored “the disenfranchisement of rural America” that has largely stemmed from the 1964 ruling.

Yet even he has doubts. “One should never say never, but I think any solution that meets the demands and the desires of rural America is a long shot.”

Countered Baird: “Rural California is dying on the vine. We should at least have an honest and fair hearing.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.