Elephant skull a big headache

Jerry Snapp loved Tiffany, and it broke his heart that he had to sell her. Close to 200 pounds, almost 4 feet tall, a foot and a half wide, she was his most beautiful skull.

He picked her up in the spring of ’97. He heard about her from a friend and wanted to know where she came from.

“The L.A. Zoo,” his friend said.

And how much did she cost?

“$500.”

The next day he rented a truck and headed off to D&D Rendering in Vernon. Tiffany was out back, her head slowly rotting in a gray plastic box, destined for a landfill if a buyer wasn’t found. Her three legs stood off to a side; no one explained the missing one.

Snapp paid cash, and a forklift dropped the box onto the truck. Once home in Riverside, he found a corner of his property sheltered from the breeze and added dermestid beetles. Soon he could hear them chewing away, a sound like a child eating Cheetos.

It took two years, and when the beetles were done, Snapp washed the skull with peroxide, named her Tiffany -- the glittery name from a tiara that he had saved from a Halloween costume -- and put her on display.

She fit right in with the assorted oddities of his Wunderkammer, the Cabinet of Curiosities, which he took on the road to renaissance fairs and craft shows. For only a buck, cameras allowed, visitors could view his collection of Neolithic weapons, shrunken heads, crystals, eggs and such phantasmagoric creations as a chupacabra, a unicorn and a mutant creature from New Guinea.

Tiffany maintained a regal and mysterious mien. Her sinus cavities looked like eyes, two flanges of bone like teeth. No one believed she was an elephant. She came from Asia, Snapp explained; that’s why her tusks were so small.

But those days were over. The recession had hit, and Snapp was broke. He had no choice but to try to sell her. It was a decision he wished he had never made.

Initially she didn’t have a name. She had come to the United States from Thailand as a baby, a gift to the children of Utica, N.Y., from the Utica Mutual Insurance Co., and the city rolled out the red carpet for her. Norman Rockwell couldn’t have painted a happier scene. It was late summer, 1966.

Clowns, Mr. Peanut, an honor guard of 12 lucky children, the mayor, Jungle George and a goat named Paula greeted her on the tarmac. Within the week, she was christened Asiannie, 7-year-old Terri-Jo Barton’s entry in a Name the Elephant contest.

In the fall, 4 million elementary school students across the country read about Asiannie in a My Weekly Reader news feature, and the citizens of Utica beamed with pride.

Two years later, she had outgrown her pen, and zoo officials considered selling her and buying another elephant rather than pay for a new home. But the children rallied, and additional space was found.

When she topped 3,000 pounds in 1971, the zoo had no choice but to sell her to a broker in Delaware. Tranquilized and in the company of Stanley the sheep, she was loaded onto a horse van when no one was looking.

Close to the Pennsylvania border, her van got stranded in a blizzard -- 23 inches in 36 hours. She almost died.

Snapp posted Tiffany on Craigslist for $9,000 on Nov. 11, 2008, and immediately heard from a collector in Toutle, Wash. They exchanged e-mails, but negotiations stopped when Snapp admitted he didn’t have documentation proving the skull was legally obtained.

Because Tiffany was an Asian elephant and because Asian elephants were endangered, Snapp realized that selling her might be a violation of the Endangered Species Act. But he was uncertain: He hadn’t imported Tiffany, and she came into the country before the act was passed in 1973.

A few weeks later, Snapp received a new inquiry, this one from a Steve who also lived in Washington state. By now Snapp had reduced the price to $4,500 and was including a rhinoceros skull for an extra $3,000. Steve was interested but wanted a friend to check it out.

On a sunny afternoon in mid-December, Snapp greeted Ed Newcomer in front of the two-story farmhouse Snapp rented. They had spoken over the phone the day before, and Newcomer had invited his cousin Lisa to join him.

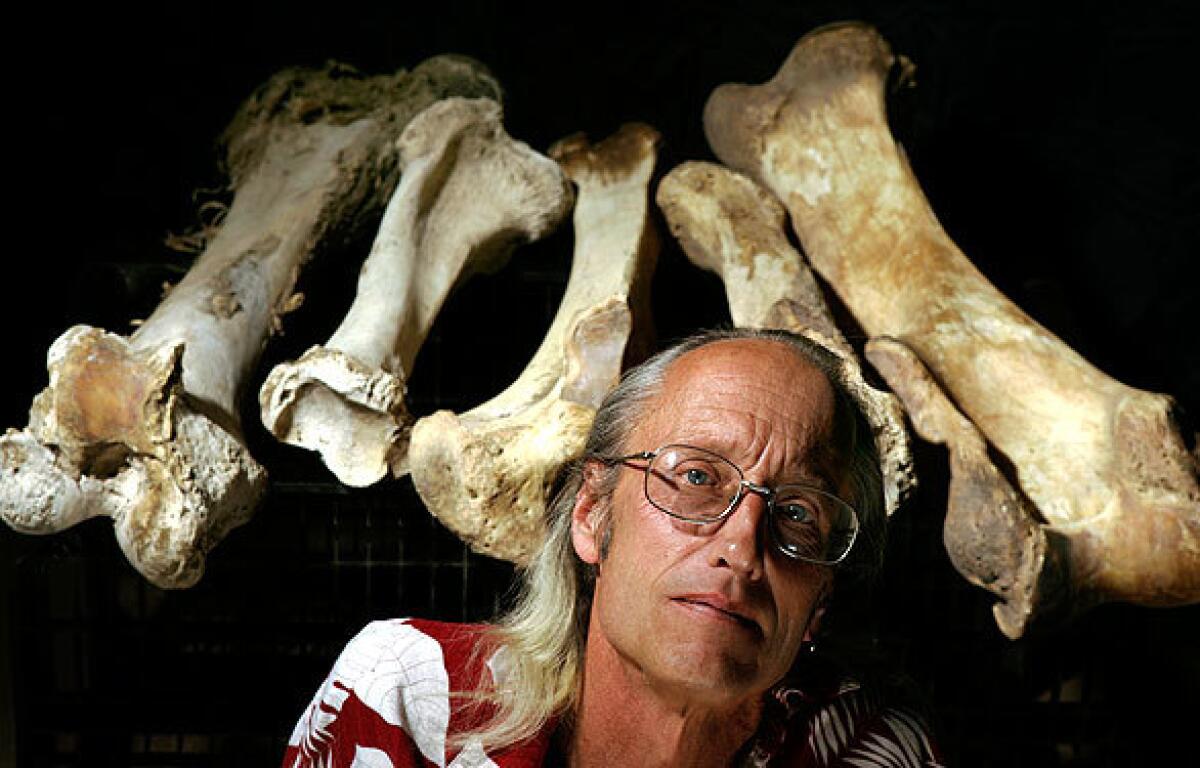

Wearing a Hawaiian shirt unbuttoned low and leaning on a cane with an elk-antler handle, his long hair tied back, Snapp looked the showman and invited his guests inside to see Tiffany.

“Man, oh, man,” Newcomer said as he walked into the living room, eager to find out what else Snapp had collected.

Asiannie survived the blizzard and ended up in a private zoo in the Allegheny Mountains. The keepers shortened her name to Annie and trained her to carry children. She lived there for 20 years until the owner closed the zoo.

Across the country, Gary and Kari Johnson didn’t need another elephant for their troupe, Have Trunk Will Travel, but they liked Annie’s calm eye. They paid $40,000 and trucked her to their 10-acre compound in Perris, Calif.

She joined the Johnsons’ retinue and went on trips to county fairs and zoos until the general curator of the Los Angeles Zoo noticed her. After a renovation of the elephant barn and yard, the Johnsons and the zoo swapped her and another pachyderm for three juveniles.

In 1994, Annie stood with the herd in Griffith Park. For three years, she was treated for ailments related to stress and age: weight loss, stiffness, a fractured tusk. One day her keepers found blood and diarrhea in the barn.

Medication, water and electrolytes proved ineffective, and at 2:45 a.m. on March 22, 1997, Annie was found dead. The cause was salmonellosis. Pathology reports indicated a possible tuberculosis infection and concern for “zoonotic potential”: Annie could infect anyone who handled her.

But by then she had been taken to the rendering plant.

Bones had always fascinated Snapp. He could remember running through Denver’s natural history museum as a little boy, staring up at the mastodon, the mammoth and the 75-foot-long brontosaurus.

No wonder he got into this business, cleaning bones, building creatures and setting up a website, trollsgarden.com, for his wares. If other companies -- Necromance on Melrose Avenue and, nationally, Art by God in Florida and Skulls Unlimited in Oklahoma -- could tap into this market, he could as well.

Then in 2008 the economy turned, and buyers pulled back. When his roommate died in September of that year, Snapp lost the extra rent and the bank foreclosed on a house he owned across the street.

He had no choice but to sell his collection.

With most of his questions answered, Newcomer told Snapp that he didn’t have the $4,500, but Steve could wire it or send a money order.

“A check is just fine if he overnights it,” Snapp said.

“A check? OK.”

“That’s all I’d ask, because . . . I’m on the edge of collapse.”

They talked about the Endangered Species Act. Snapp offered to research the law.

“That’s good,” Newcomer said. He then properly introduced himself. “Lisa and I are both special agents with the Fish and Wildlife Service.”

In Newcomer’s waistband was a pistol. In his pocket was a recorder that captured every word spoken during the interview with Snapp.

In his six years with the Fish and Wildlife Service, Newcomer had worked his share of high-profile cases -- a killer of hawks, an importer of rare butterflies -- but he had never heard of anyone selling an elephant skull.

In the end, he wasn’t concerned that it had come from the zoo. That it was on the market was enough. It fueled an appetite for endangered species, and his job -- indeed, the government’s job -- was to stop the trade of illegal wildlife products in the United States. It may not be the crime of the century, but it was still critical for the agency to pursue.

“Are you guys really out here to get me into trouble?” Snapp asked.

After the agent in Washington, Steve Furrer, initiated the undercover operation with his e-mails to Snapp, Newcomer’s job was to learn whether Snapp knew that selling the skull across state lines was illegal and whether he was a regular in the trade.

Private parties often put items for sale on the Internet -- heirlooms, jewelry, furs made from endangered species -- without knowing those ads are illegal. Selling within a state is sometimes allowed, but market them across state lines and it’s a misdemeanor. Transport them and it’s a felony.

“What am I doing wrong here?” Snapp asked.

Newcomer had determined that Snapp knew he was breaking the law. There was enough evidence, Newcomer said, for misdemeanor charges.

With the help of two wardens from the state Department of Fish and Game, Newcomer loaded Tiffany and the rhino skull into the van. Afterward, Newcomer and Snapp chatted a little more, reminiscing about their childhoods.

They had both grown up in Denver. Snapp was 11 years older than Newcomer, but as kids they had visited the zoo’s Pachyderm House, and they both remembered Cookie, the resident elephant.

Snapp pleaded not guilty to the charges that he had illegally offered to sell endangered species in interstate commerce.

He may have broken the letter of the law, but as he saw it, he hadn’t endangered any species by trying to sell the skull. He saw himself as no different from piano manufacturers who ship antique ivory keys around the country with impunity. He hoped a jury would agree.

“All rise.”

Court was in session at the Edward R. Roybal Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles. The Honorable Ralph Zarefsky took his seat.

Covered by a tarp, Annie was on a cart beside Newcomer, who sat with the prosecution. Once the jury had been selected, Assistant U.S. Atty. Dennis Mitchell laid out his case, and defense attorney Anthony Eaglin painted his client as a museum curator who’d fallen on hard times.

The government put its witnesses on the stand: the man who tipped off the agency to the ad; the agents who assisted Newcomer; a forensic morphologist who identified the skull; and Newcomer himself.

The defense called no one, and when the trial moved into closing arguments, Mitchell kept to the facts and Eaglin to an element of doubt. Snapp had received no money, his attorney said, and he transported the skull nowhere.

Within two hours, the jurors had reached their decision. As they waited to be called back to the courtroom, they talked, dumbfounded that the government had taken this case as far as it did. They wondered about the expense of the trial and what example Snapp could be.

Once in court, Juror No. 8 passed the verdict to the judge.

Snapp stood.

Guilty.

Almost four months later, the judge sentenced Snapp to three years’ probation with home detention and electronic monitoring for three months. He must perform 100 hours of community service. All fines were waived because of Snapp’s inability to pay. He also forfeits ownership of Annie.

The U.S. government now owns Annie. She resides in a warehouse in Torrance, surrounded by other items of the illegal wildlife trade: a tiger, a rhino head, lizards.

Since Snapp’s conviction, Newcomer contacted Cal State Northridge, the Natural History Museum and the Los Angeles Zoo to see if they might put Annie on display. The zoo seems most interested, but details still need to be worked out.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.