Treasure trove of surfing photos is a wistful wave to the past

Hard to imagine, but in the 1950s there were no more than a couple hundred surfers in Southern California. Spying one of these early adopters gliding across the waves was a rare treat.

Rarer still were the people who photographed them.

They captured the early legends of modern surfing before they became household names. And they caught the spirit of an emerging California beach culture that was soon to sweep across the nation.

At the time, no one thought this was history in the making. Photographers gave away their images. Entire photo archives were lost or destroyed.

PHOTOS: A photographic wave back in time

“We didn’t respect them as pictures that would have meaning in the future,” said John Severson, 79, who began photographing surfers in 1950 and would later found Surfer magazine.

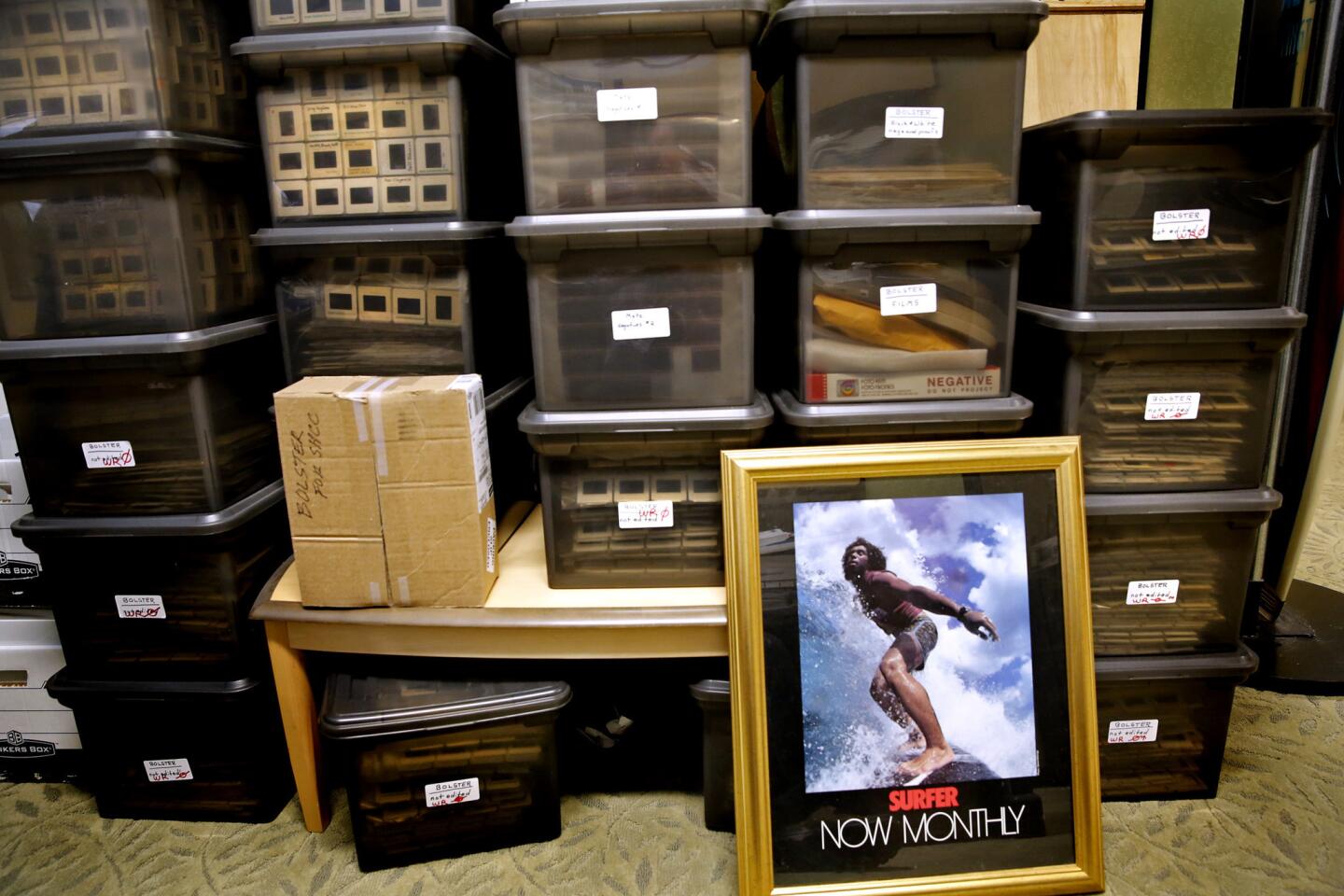

The Surfing Heritage and Culture Center in San Clemente is working to turn back the clock. Its decade-long effort to collect and preserve early surfing photos has yielded a treasure trove of more than 200,000 images.

“Surfing has an origin story that everyone loves,” said Matt Warshaw, author of “The Encyclopedia of Surfing.” “It’s the story of kids on the beach inventing this whole thing that today is a zillion-dollar industry.

“That’s why those pictures are so important. They’re the illustrated version of that creation story.”

In the 1930s, long before telephoto lenses, surfboard designer Tom Blake built a waterproof housing for his camera that allowed him to paddle out for close-up shots. His groundbreaking work for National Geographic magazine introduced this exotic sport to much of the world.

John “Doc” Ball, a dentist by trade, followed Blake into the water, inventing new equipment and techniques to chronicle California’s nascent surf culture before World War II.

Ball photographed LeRoy Grannis surfing off Hermosa Beach and later mentored him when a doctor recommended Grannis find a hobby to relieve stress from his job as a telephone installer.

“I grew up on the beach surfing. I started selling photos of my friends out of my garage for a dollar apiece,” said Steve Wilkings of his teenage years in Hermosa. “For a little kid, that was pretty neat.”

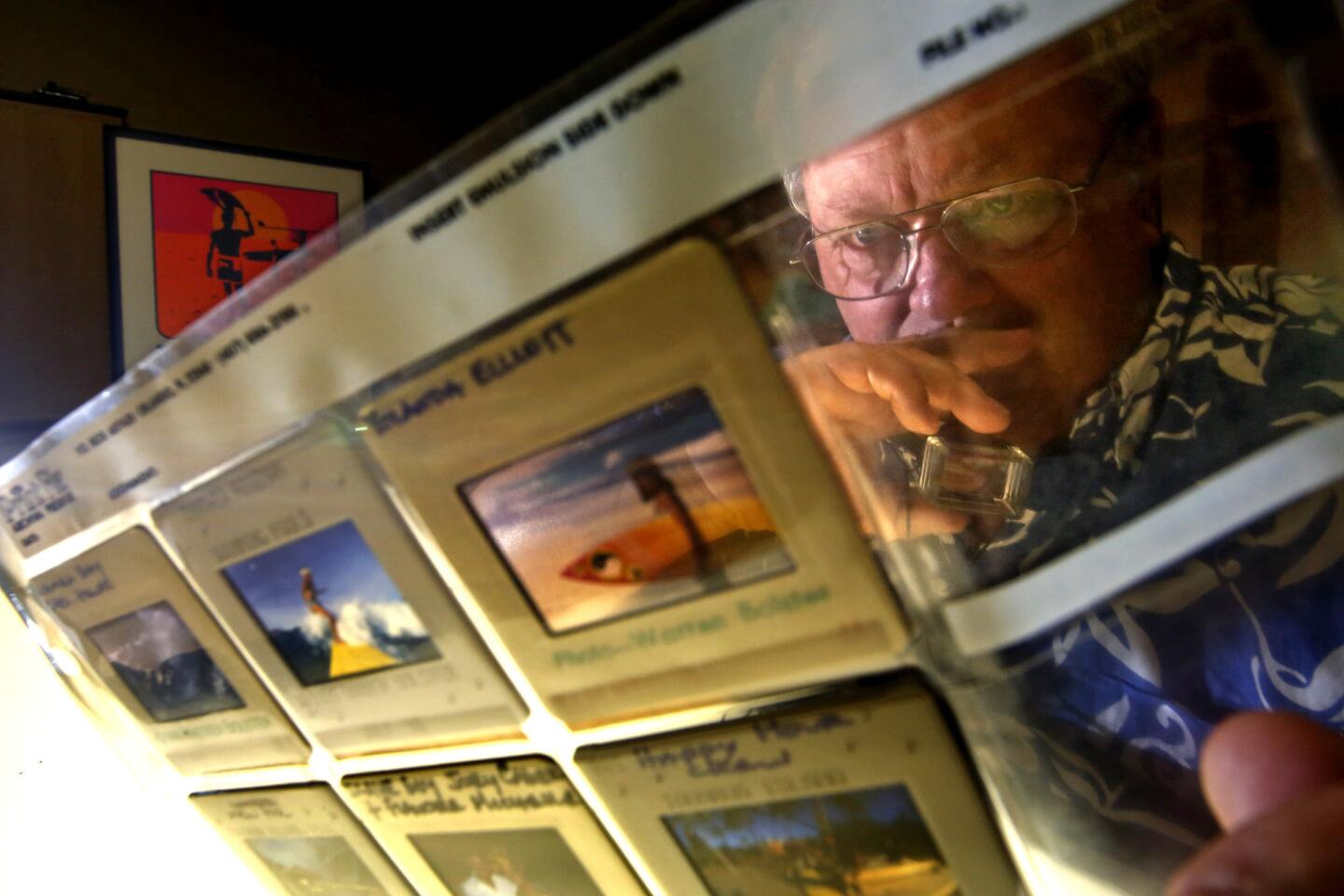

Wilkings is the archivist of the San Clemente photo collection and worked for decades as a professional surf photographer. He has digitized and edited about a quarter of the center’s collection. At 66, he figures someone else will have to finish the job.

“We got so much stuff, sometimes it’s overwhelming,” he said.

Wilkings was mentored by Grannis, and images taken by him, Ball, Blake and others are part of the enormous collection of prints, slides and copied images.

Some of the 140 collections held by the center are encyclopedic — thousands of photos of surfers hanging ten on longboards, dropping into steep pitches or shooting through curls.

Others are more personal: Ghostly snapshots of silhouetted riders taken by a bodybuilder who kept his camera dry by keeping it in a coffee can when he wasn’t shooting. A portfolio made of wood containing prewar Hawaiian scenes taken by a service member stationed at Pearl Harbor.

When an architect named Don Davis wanted to document early 1960s surf culture at “California’s Waikiki” — San Onofre beach in northern San Diego County — he turned his lens from the water to the sand.

His handmade book of black-and-white Polaroid portraits — along with the name, address, phone number and occupation of his subjects — captures the time’s free-spirited innocence.

“The single fellows have especially requested the phone numbers of the single girls,” Davis wrote in a foreword explaining his project, which was donated to the center by Davis’ widow.

There are salesmen and secretaries in swim trunks. Young men and women next to cars with fins and boards as long as roofing joists.

On one page, there’s Marshal Matt Dillon — “Gunsmoke” actor James Arness — and his son Rolf, who’d become a surfing world champion. On another page, pioneering surfboard shaper and soon-to-be-wealthy entrepreneur Hobie Alter moons the camera.

“Compared to the action shots, the cultural photos taken back then were seen as the throwaways,” Warshaw said. “But it’s the pictures of surfers not surfing that have become more and more interesting with time. They speak to the romanticism of the time.”

Some work from that era is now considered high art. Grannis’ work, for instance, has been sold by galleries. A signed, limited-edition hardcover book of his photos published by Taschen in 2007 sold for $1,500.

The nonprofit San Clemente center generates income from licensing agreements it has with some of its collections.

But the main purpose of amassing the images is to preserve the story of a way of life that helped define California. Students, authors and researchers from as far away as England have pored over the collection.

“But,” added Wilkings, “we also get a lot of calls from the children of people who ask, ‘You got pictures of my dad surfing Pipeline? I’d like to get a photo of him for Father’s Day.’”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.