Death’s lessons learned

My grandmother never liked my name.

Her eldest son, my father, had given me his name, though everyone knew that was taboo in Chinese tradition. So my grandmother insisted on calling me by the name she had given me: Lin Da. Last name first, in the Chinese way. Loudly, in her way.

I called her Ah-Ma -- Taiwanese for grandma.

When I didn’t understand what she was saying, which was often, she would utter a few sentences in Taiwanese that I knew from years of repetition: “Why don’t you understand Taiwanese? You are so American!”

In truth, I was a mystery to her and she to me.

It was only after an unexpected loss shook our family that I finally began to understand her and what she had given me.

::

Like many children of immigrants, I grew up in a household mindful of its roots but determined to grasp the American experience.

My father occasionally took me to the Buddhist temple near our home in San Francisco’s Chinatown. My mother took me to summer camps to connect with Taiwanese culture.

But Thanksgiving and Christmas were the big holidays in our family. English was the dominant language in our home, and my parents didn’t even mind that, as a child, I didn’t know how to use chopsticks.

Each summer beginning when I was 9, though, I was taken to Taiwan to see my grandmother.

I remember that she rarely smiled, and her clothes smelled of Si wu tang, a mixture of Chinese herbs.

During my visits, she would rise before daybreak and head to the market to gather the ingredients for her bamboo-and-clam soup, ginger tsai-guei squash and pan-fried, black-bean fish.

For lunch, she opened clams for me. For dessert, she poured out generous scoopings of Aiyu jelly, a yellow gelatinous dessert cut in cubes and eaten in syrup with ice and sugar -- much better than Jell-O.

On holidays, she burned yellow bits of paper, representing money, as an offering to gods, ghosts, or our ancestors, depending on the occasion. Before we could eat, she first asked their permission. My father would often translate for us. But when he left, the room would fall uncomfortably silent. “That was delicious,” I’d say in Taiwanese, exhausting my vocabulary.

Throughout her life, my grandmother was guided by a set of beliefs -- drawn from Buddhism, Taoism and Taiwanese folk religion -- that were baffling to me.

I wasn’t particularly religious, and death wasn’t something I thought about. That changed last November, when my 7-year-old nephew, Trevor Ron Lin, was infected with the H1N1 virus and suddenly died in upstate New York.

I was distraught. I found myself at the Hsi Lai Temple, the large Buddhist temple east of Los Angeles. It was the first time I had been alone in a Buddhist place of worship, and I didn’t know what to do.

There were statues representing Buddhas and bodhisattvas -- enlightened beings on the path toward becoming Buddhas. Which one was I supposed to pray to? How many times was I supposed to bow? What were those words my grandmother mumbled when she prayed?

I realized I didn’t know how to pray.

::

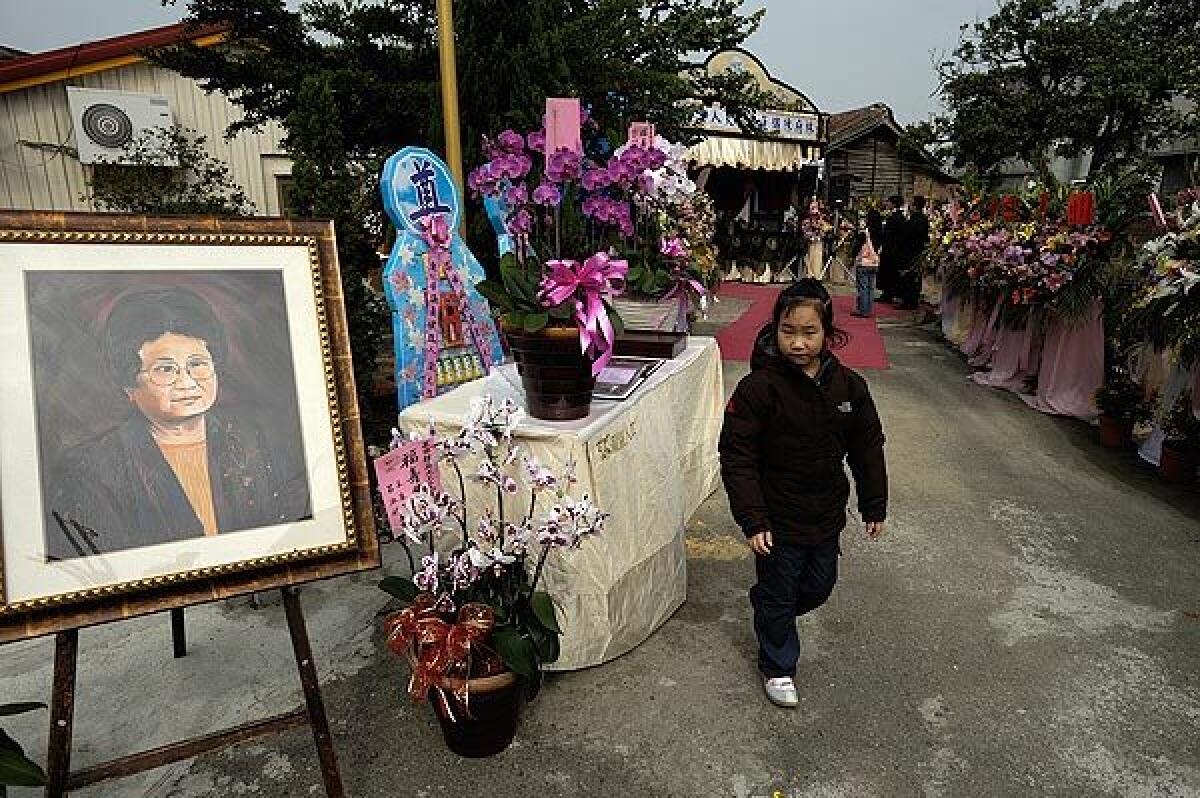

My grandmother died exactly one month later, and the funeral preparations began immediately. Her body was delivered home from the hospital, and every morning and evening, food was taken to her coffin.

When I arrived, one of my aunts brought me to see the coffin. She announced my arrival and told me to say something to Ah-Ma.

My mind was blank. I didn’t have the words in Taiwanese to respond.

Later, the family gathered to read aloud Buddhist sutras. The readings began in Taiwanese, but it quickly became clear that my family could not keep up.

My parents, aunts and uncles had spoken Taiwanese growing up, but they were taught to read in Mandarin, the state’s official language. My grandmother, raised during the era of Japanese occupation, hadn’t been fluent in Mandarin.

“Would she understand the sutras if they are read in Mandarin?” my uncle asked.

“It doesn’t matter what language you read it in,” a nun reassured him. “Japanese, Mandarin -- she will understand it all.”

At an old melon field not far from Ah-Ma’s home, we gathered to burn a 5-foot-tall paper house. With a red roof and high ceilings, it had everything she would need in her next life and more: a kitchen, two bedrooms, a DVD player -- even a Mercedes-Benz, though in life she had not owned a car and didn’t know how to drive.

Dropped on the lawn were hundreds of yellow lotus flowers also made of paper. They were intended to help my grandmother rise past the 108 demons that might try to stop her from reaching her next life.

On a windy, overcast afternoon, we all held a red ribbon that encircled the burning paper house, and watched the black smoke flutter to the sky.

::

How old was Ah-Ma? By Western reckoning, she was 88. Chinese accounting, which includes the time since conception, would have made her 89 -- but the funeral director, with my family, rounded her age up for good luck.

So, she was 90.

On the day of the funeral, my aunts and uncles gathered in front of the coffin to tell my grandmother stories. An aunt recalled how, half a century earlier, Ah-Ma had worked so hard on the family’s farms that she didn’t get home until well after nightfall.

“Sometimes,” my aunt said, “I would be hungry until 9 o’clock at night. We would lie in bed surrounded by mosquitoes, too weak from hunger to fight them from biting us.”

She continued:“The first day of each semester, you would always worry about not having enough money to pay for school tuition. All these memories came through my mind when I heard about your passing. I felt so much pain inside.”

I was surprised to learn how poor my grandmother, who had seven children, had been. That explained why she put so much pressure on my father to do well in school and become a doctor. She once told him: “If you don’t study hard, it is worthless to have you as a son.”

Now I understood why my parents had always pushed me and my siblings to become physicians.

As I listened to the stories of my grandmother’s hard work, tears streamed down my face.

::

At noon, it was time to bring Ah-Ma to her final resting place.

My father carried a paper lantern, and my older brother carried her spirit tablet -- a placard bearing my grandmother’s name.

An uncle held an umbrella over the tablet, a funeral tradition dating to the Japanese occupation. The umbrella blocked the deceased’s view of the sky, which was said to be under the rule of the Japanese emperor.

We arrived at the Forensic Medical Autopsy Center of Hsinying, and walked downstairs to a large, white room. A machine slid the coffin into a steel tube, and orange-yellow flames quickly engulfed it.

“Leave, Ah-Ma!” we shouted, urging Ah-Ma’s spirit to leave her body while the coffin burned.

Several hours later, we returned to receive her ashes. Using tongs, family members took turns placing her bones into her urn. “Ah-Ma, this is your new home,” we said.

We took the urn to the columbarium, which houses the ashes of the deceased, and placed it on a shelf. Then, it was time for us to leave. One by one, we lined up to say a few words to Ah-Ma.

When my turn came, I stared into the urn, head bowed, palms clasped together.

I took a deep breath, and I prayed.

I realized that the rituals passed down by my ancestors were helping to ease my grief over the loss of Ah-Ma and my nephew. And I began to believe that death could be a door to a new state of being, for them and for me.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.