L.A. Unified pays teachers not to teach

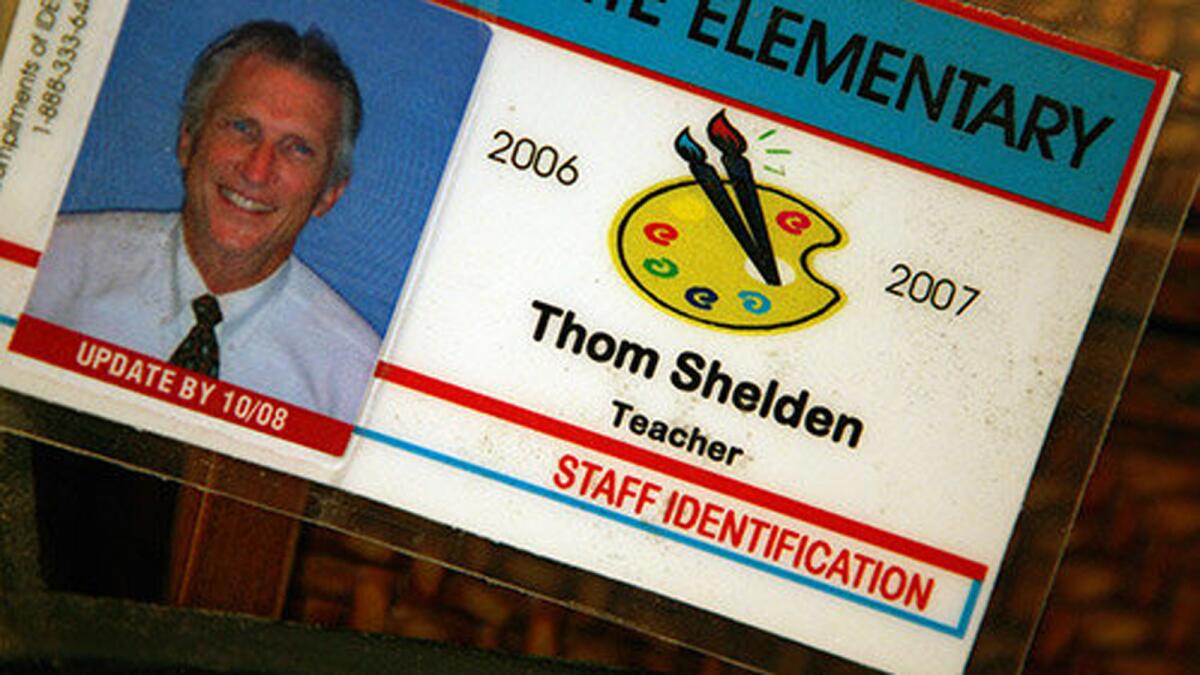

For seven years, the Los Angeles Unified School District has paid Matthew Kim a teaching salary of up to $68,000 per year, plus benefits.

His job is to do nothing.

Every school day, Kim’s shift begins at 7:50 a.m., with 30 minutes for lunch, and ends when the bell at his old campus rings at 3:20 p.m. He is to take off all breaks, school vacations and holidays, per a district agreement with the teacher’s union. At no time is he to be given any work by the district or show up at school.

He has never missed a paycheck.

In the jargon of the school district, Kim is being “housed” while his fitness to teach is under review. A special education teacher, he was removed from Grant High School in Van Nuys and assigned to a district office in 2002 after the school board voted to fire him for allegedly harassing teenage students and colleagues. In the meantime, the district has spent more than $2 million on him in salary and legal costs.

Last week, Kim was ordered to continue this daily routine at home. District officials said the offices for “housed” employees were becoming too crowded.

About 160 teachers and other staff sit idly in buildings scattered around the sprawling district, waiting for allegations of misconduct to be resolved.

The housed are accused, among other things, of sexual contact with students, harassment, theft or drug possession. Nearly all are being paid. All told, they collect about $10 million in salaries per year -- even as the district is contemplating widespread layoffs of teachers because of a financial shortfall.

Most cases take months to adjudicate, but some take years.

Kim, 41, has persisted the longest.

He argued unsuccessfully in a lawsuit that he was the victim of disability discrimination. Born with severe cerebral palsy, he has limited use of his limbs, must use a wheelchair and requires a full-time personal aide (who is paid about $14 an hour by the district). He declined repeatedly to be interviewed, as did his attorney, Lawrence Trygstad.

Kim’s long-term stay in paid professional limbo highlights how long it can take to move through the thicket of legal protections afforded educators in the Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second-largest.

“It’s a glaring example of how hard it is to remove someone from the classroom and how the process is tilted toward teachers,” said school board member Marlene Canter, who recently proposed -- unsuccessfully -- to revamp the disciplinary process.

National issue

The problem of what to do with teachers in trouble extends well beyond Los Angeles Unified. But not every district in California, or the country, handles it the same way.

In New York City public schools, which make up the country’s largest district, teachers are confined to “rubber rooms.” About 550 of the district’s 80,000 teachers spend school hours “literally just doing crossword puzzles, waiting for the end of the day” until their cases are resolved, spokeswoman Ann Forte said. Some have been there for years.

In Chicago, the dismissal process moves faster and the 30 teachers waiting for their cases to be resolved are assigned clerical tasks. “They’ve got to be doing something,” senior assistant general counsel James Ciesil said.

San Francisco Unified employees are either sent home or assigned to tasks such as working in warehouses, doing inventory or answering phones, said Jolie Wineroth, the district’s senior executive director for human resources.

“I don’t want to give anyone a free vacation,” she said.

Former union leaders say teachers in the Los Angeles district used to be assigned non-teaching jobs when they were housed. “They should not just sit there like zombies,” said Hank Springer, United Teachers Los Angeles president from 1975 to 1980.

But the practice has changed in the last dozen years or so. Now, district officials say, they are prohibited from assigning chores under the contract with the teachers’ union. Although there is no specific reference in the contract to housed employees, an attorney for L.A. Unified pointed to Article 9, Section 4.0, which defines the “professional duties” of a teacher, such as instructional planning and evaluating the work of pupils.

With no mention of photocopying, stuffing envelopes or answering telephones in the contract, the district and union have interpreted this provision as prohibiting clerical duties.

“Why would we denigrate [teachers] by forcing them to do something they’re not supposed to do?” said A. J. Duffy, who is now president of UTLA, adding that housed teachers are entitled to a presumption of innocence.

Los Angeles Unified Supt. Ramon C. Cortines thinks the policy should be changed. “I don’t believe they should just be sitting -- that’s taxpayer money,” he said.

Some employees newly housed by L.A. Unified are dissatisfied with the practice for a different reason: They haven’t been told what they are alleged to have done, nor whether the district is planning to fire them.

“Prisoners in Guantanamo Bay have more rights than I do,” said Jeffrey Brown, a ninth-grade teacher at Fulton College Preparatory School in Van Nuys.

In a lawsuit filed against the district in April, Brown alleges that he has been housed for roughly 70 days but told nothing about why.

His lawyer, Joseph Hart, said he was amazed at the secrecy of the system and its lack of regard for individual rights. “I’m surprised nobody has challenged it in court before,” he said.

District officials said that with rare exceptions, employees are informed all along of the allegations against them.

Misconduct complaints

Despite severely restricted movement and speech that was hard to understand, Kim racked up remarkable achievements before beginning his teaching career.

As a child he learned to paint with a brush and to type with a stick -- both held in his mouth. He earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from UC Berkeley, then went on to get two master’s degrees, one in astrophysics and the other in special education. He was also active in the disability rights movement.

When he applied for a full-time teaching job, he was turned down by more than 15 schools in L.A. Unified, he said in a 1999 letter filed in court. Only after he threatened to sue the district for disability discrimination did he get a teaching job at Grant High School, records show.

Kim’s troubles with the district began in 2000, when a classroom aide reported inappropriate comments and advances.

In class one October day, according to her testimony before an administrative panel, Kim asked her to stand closer to him while interpreting his speech for the students. When she moved closer, she said, he touched her breast with his left hand, the only one he could slightly control.

Students immediately started making comments about what they’d seen. One said: “Oh, come on, Mr. Kim, you know you liked it,” according to a summary of allegations against Kim prepared by a state review panel in 2008. Kim responded to the students that he had.

Over the next two years, another adult andsixstudents would make similar complaints against Kim,according to the summary.

The same month the aide complained, Kim asked a girl if she had a boyfriend and if she was a virgin, according to the girl’s testimony during an administrative hearing.

Another girl said that Kim kept staring at her and urged her at one point not to change her hair color, according to documents filed with the state.

Joseph Walker, then the principal at Grant, confronted Kim, who denied most of the allegations. Walker then wrote a memo to the teacher telling him that it was important “to stay out of the students’ personal life and personal space,” according to district records filed in court.

It was the first of several attempts by the principal to bring the teacher into line. In addition to chastising him for his conduct, he also found fault with Kim’s teaching skills.

“Communication with the students is a slow and laborious process leading to frustration and loss of instructional time,” Walker wrote in a letter later filed in court.

In 2002, Kim passed a major milestone: his second anniversary with the district. Under state law, he was now a tenured teacher, entitled to a detailed set of protections. These included taking the district to an administrative review hearing and to court.

Difficult process

Complaints of misconduct kept coming, according to district records filed in court.

After a male classroom aide reported that he had seen Kim touch a girl on the shoulders and near her crotch, Walker asked for advice from L.A. Unified’s personnel division. The principal noted that Kim “has been charged with sexual harassment for the fourth time within a one-year period,” according to his December 2001 memo in court files.

Two months later, a school counselor complained that Kim ran his hand back and forth across one of her breasts during a meeting, according to the court filings and the commission summary.

Walker now wanted Kim out, and the district personnel department agreed.

“I wasn’t big on firing people because I knew what you had to go through,” Walker said in a recent interview. He also was afraid Kim would sue him for discrimination.

But after so many complaints, Walker said he had no choice. “I was really compelled to do something,” he said.

In February 2002, the district ordered Kim housed at an administration building while the allegations were formally investigated. The school board voted to fire Kim in October 2003.

For seven years, the district and Kim have battled in administrative forums and courtrooms.

Kim sued Walker and the district for disability discrimination and ultimately lost. By then, Walker had retired -- exhausted, he said, by the battle to fire Kim. He currently heads a charter school in Pacoima.

Separately, a Commission on Professional Competence -- a three-member panel with ultimate administrative authority over teacher firings -- concluded that Kim had indeed engaged in unprofessional conduct by touching three female students. But, the panel decided, he should not be fired because “his conduct was a result of poor judgment, rather than overtly sexual.”

The panel found no evidence that Kim was a poor teacher or that he had injured his students. Instead it faulted the district for poorly documenting its case and not informing Kim promptly of the allegations.

The district successfully appealed to the superior and appellate courts, which sent the case back to the commission for reconsideration. Earlier this year, the commission backed Kim again, ruling this time on a 2-1 vote that all of the touching was the result of “involuntary arm movements.”

And so it goes on, with no end in sight. As Kim continues to collect his teacher’s salary, the district is planning yet another court appeal.

latimes.com /teachers Other stories in the series, readers’ comments, more photographs, an audio slide show and graphics are online.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.