Tennessee uses incentives to change a troubled foster care system

Private foster care agencies in California are paid a set fee for each child — about $1,870 per month to cover the cost of care and administration.

The payment system has created an inadvertent incentive for some foster agencies to scrimp on care and lower standards on foster parents so they can take on more children.

Over the last two decades, a group of states has begun to take a new approach based on setting big incentives — and big penalties.

The basic strategy has been adopted by at least 12 states across the country, including Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, Florida and Tennessee.

Tennessee had one of the worst foster care systems in the country.

Foster parents were leaving the system. Children were abused at high rates, and nearly a quarter of them had lived in 10 or more places.

After a lawsuit by children's advocates was settled in 2001, the state made a change. Instead of paying private contractors a fixed fee for each child, the state created a system of severe punishments and incentives.

Private foster family agencies could earn bonuses of tens of thousands of dollars if they moved children out of foster care into permanent settings, either by reuniting them with their parents or having them adopted by other families.

THE CHILD MILL

Private foster care system, intended to save children, endangers some »

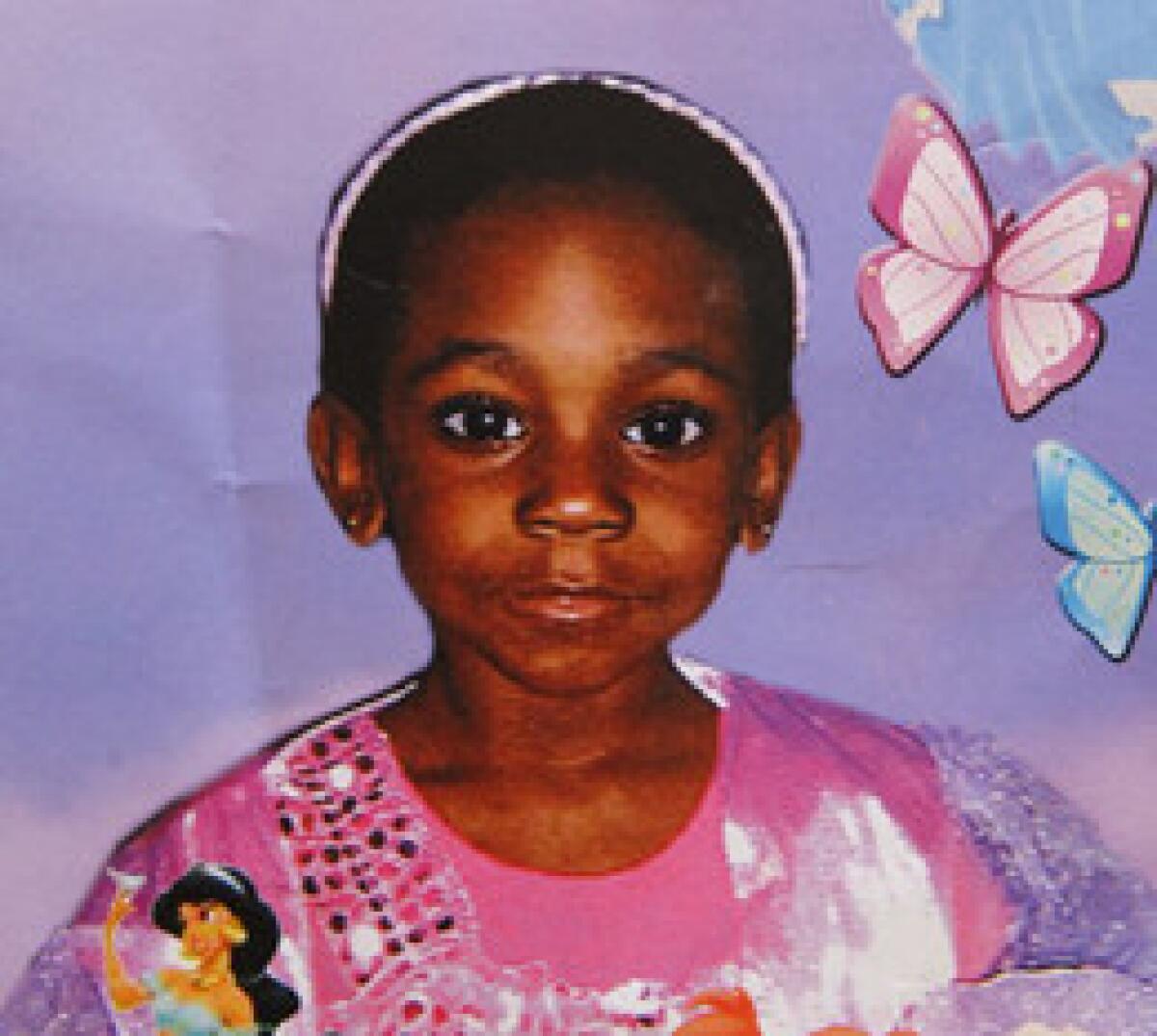

Jada's story: Scars of abuse »

At the same time, foster family agencies could also be penalized tens of thousands of dollars if children fell out of their placements within a year.

The new system theoretically would winnow out weak and abusive agencies, while rewarding safe and effective ones. More than half of the state's private foster care agencies did not survive the transition.

The state has recently relaxed its imposition of penalties, giving agencies more time to correct problems.

"Tennessee is no longer buying just a service," said Fred Wulczyn, a researcher at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, and a lead architect of the Tennessee program. "They are buying a good outcome for the child."

The incentive system has pushed agencies to monitor themselves for abuse problems and move children out of foster care into permanent homes as quickly as possible.

Tennessee is now first in the nation for successfully finding permanent homes for children who previously spent more than two years in foster care. California, in comparison, ranks 27th.

But Bowen McBeath, a professor of social work at Portland State University in Oregon, cautioned that the systems can still be vulnerable to abusive and fraudulent contractors.

"You have to monitor those contracts better because it creates opportunities for gaming," he said. "You can't just leave everything to the market. You might think it requires less government, but it actually requires more."

Follow Garrett Therolf (@gtherolf) on Twitter

Produced by Lily Mihalik and Evan Wagstaff.

More from the series: A private system |Scars of abuse

More foster care coverage

Problems proliferate at private foster care agency

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.