Reporting from MONTECITO, Calif. — Charles McCaleb hasn’t slept much since the raging Thomas fire chased him out of his Ojai Valley home about a week ago.

In the early morning hours, he refreshes fire and weather websites for the latest on the blaze’s behavior and spread. During the day, he volunteers, doling out masks to evacuees from behind a table off Highway 192 in Montecito.

His voice is gravelly from days of exposure to toxic air, his nerves rattled by the seemingly endless firefight.

“It’s not like ‘someone pointing a gun at you’ scared,” said McCaleb, 70. “It’s more of a controlled fright where you know what’s happening.”

Anxiety was high for residents of Santa Barbara County, where the Thomas fire, driven by gusty winds and bone-dry air, rampaged over the weekend, destroying more homes, forcing tens of thousands more people to flee and threatening the coastal enclaves that are a defining feature of California’s landscape.

The spread of the flames slowed Monday as winds calmed and the fire reached areas that had burned about a decade ago, reducing the available fuel. The blaze grew by only about 1,000 acres, compared with the more than 50,000 Sunday, when it chewed through steep slopes and canyons that haven’t burned for decades. By Monday evening, firefighters had the massive wildfire 20% contained.

“It’s a good sign,” Ventura County Fire Engineer Steve Swindle said of the 231,700-acre fire’s slower growth. “It gives us some hope.”

Firefighters were focusing efforts on keeping flames from damaging hillside homes in Montecito, Summerland and Carpinteria. The fire is burning above those towns, along a ridgetop in the Santa Ynez mountains.

Authorities said Monday night that the fire was “flanking,” or moving slowly side to side along the ridgeline. But forecasters fear so-called sundowner winds could pour over the ridgetop from the interior valley and blow the fire down the hill into coastal neighborhoods.

A gray haze hung over Montecito, where stores and gas stations in the evacuation zone north of Highway 192 were closed and only a scattering of residents stayed behind. Fire crews went door-to-door looking for holdouts and water sources, such as homes with pools or wells they could draw from should the Thomas fire bear down on the city. Others watched for flying embers that could ignite spot fires.

Roger Raines, a battalion chief with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, and his platoon were assessing the vulnerability of about 50 multimillion-dollar Montecito estates connected by a tangle of narrow, winding tree-lined roads barely wide enough for the trucks assigned to protect them. Residents who fled left their front gates wide open for easy access.

Raines sat in his truck at Park Lane and East Mountain Drive, just outside the open field his team had designated as a safety zone to regroup should things turn for the worst. Their success would depend on the wind, which forecasters said could gust downhill at up to 25 mph after dark.

His crew was new to the Thomas fire, but they had been fighting flames for a week — first in Bel-Air, where the Skirball fire scorched more than 400 acres, then Murrieta, battling the smaller Liberty fire.

“This is our first shift here,” he said. “But we’ve been running for a week.”

Just two months ago, Raines was in Napa County fighting the devastating wine country fires that claimed more than 40 lives.

“It’s December,” Raines said. “This doesn’t happen in December.”

1/73

John Bain and Brandon Baker try to stop a fire from burning a stranger’s home in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 2/73

A brush fire moving with the wind sends embers all over residential neighborhoods north of Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 3/73

A family packs up and evacuates as a brush fire gets closer to their home in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 4/73

John Bain and his friends, all from Camarillo, came to help as brush fires move quickly through residential neighborhoods in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 5/73

Strangers band together to help put out a palm tree on fire and stop it from burning homes.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 6/73

The Hawaiian Gardens apartments burn in Ventura.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 7/73

Residents help with the fire attack on Buena Vista Street in Ventura.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 8/73

Residents watch the Thomas fire on Prospect Street in Ventura.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 9/73

Firefighters are deployed to battle the fire in a Ventura neighborhood.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 10/73

A chimney is all that stands of a home as a brush fire continues to threaten other homes in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 11/73

Remnants of a home as a brush fire continues to threaten other homes in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 12/73

A home burns on a hillside overlooking Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 13/73

Palms are consumed in the Thomas fire.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times ) 14/73

Emma Jacobson, 19, center, gets a hug from a neighbor after her family home was destroyed by fire in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 15/73

Olivia Jacobson, 16, wipes tears as she looks at her family’s home, destroyed by the brush fire on Island View Drive in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 16/73

Aerial view of the Thomas fire in Ventura County.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times) 17/73

Noah Alarcon carries a cage with the family cat while evacuating from Casitas Springs.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 18/73

Smoke from the Thomas fire crosses over Lake Casitas near Ojai.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 19/73

A Ventura County firefighter battles a blaze on Cobblestone Drive near Foothill Road in Ventura.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 20/73

Ventura County Firefighter Aaron Cohen catches his breath after fighting to save homes along Cobblestone Drive near Foothill Road in Ventura.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 21/73

Aerial view of homes burned to the ground in the Thomas fire in Ventura County.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times ) 22/73

A home between Via Baja and Foothill Road burns in Ventura.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 23/73

Amanda Leon and husband Johnny Leon watch as firefighters fight to save homes along Cobblestone Drive near Foothill Road in Ventura.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 24/73

Chino Valley firefighters fight to save a home along Cobblestone Drive near Foothill Road in Ventura.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 25/73

Embers continue to burn at sunset Tuesday in a home on Ridgecrest Court at Scenic Way in the Clearpoint neighborhood of Ventura.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles TImes) 26/73

A firefighter battles the Thomas fire along Highway 33 in Casitas Springs.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 27/73

Firefighters try to protect homes from the Thomas fire along Highway 33 in Casitas Springs.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 28/73

A firefighter battles the Thomas fire along Highway 33 in Casitas Springs.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 29/73

Edward Aguilar runs through the flames of the Thomas Fire to save his cats at his mobile home along Highway 33 in Casitas Springs in Ventura County.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 30/73

Jeff Lipscomb, left, Gabriel Lipscomb, 17, center, and Rachel Lipscomb, 11, look for items to recover from their burned home in Ventura.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 31/73

A traffic collision temporarily clogged lanes on the northbound 101 Freeway between Solimar and Faria Beaches as the Thomas fire burned in the hills.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 32/73

The Thomas fire burns towards the 101 Freeway and homes between Solimar and Faria Beaches.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 33/73

Fire personnel keep an eye on the Thomas fire on Toland Road near Santa Paula.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 34/73

A train on the Rincon coast passes a burning hillside from the Thomas fire.

(Michael Owen Baker / For the Times) 35/73

The Thomas fire burns along the 101 Freeway north of Ventura on Wednesday evening.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 36/73

A firefighter battles the Thomas fire in the town of La Conchita early Thursday.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 37/73

A resident cries as the Thomas fire approaches the town of La Conchita early Thursday.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 38/73

Burned palm trees are left standing between the 101 Freeway and Faria Beach as the Thomas fire reaches the Pacific Ocean.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 39/73

Firefighters battle Thursday to protect the resort city of Ojai from encroaching flames.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 40/73

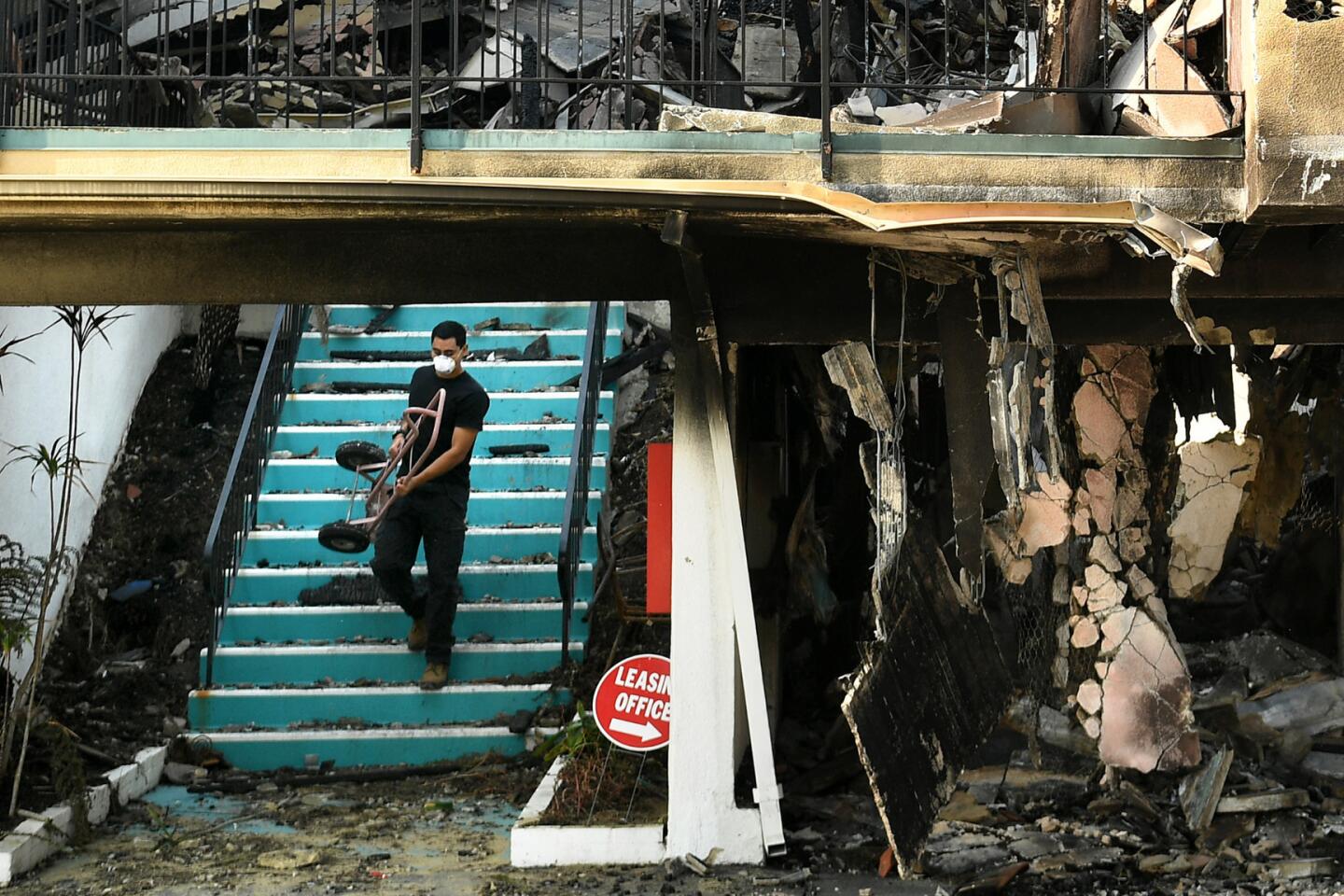

Casey Rodriquez helps a friend move belongings after the Thomas Fire destroyed most of an apartment building on North Kalarama in Ventura.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 41/73

A burnt-out bus near Maripoca Highway.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 42/73

The Thomas fire burns in the Los Padres National Forest, near Ojai.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 43/73

A huge plume of smoke rises north of Ventura as seen Sunday afternoon from the Ventura pier, as the Thomas fire threatens parts of Carpenteria and Montecito.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 44/73

The Thomas Fire burns in the Los Padres National Forest, near Ojai, Calif. on Friday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 45/73

Residents react as they watch the Thomas Fire burn in the hills above La Conchita at 5 am Thursday moning.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times) 46/73

Mary McEwen and husband Dan Bellaart prepare to evacuate their home on Toro Canyon Road in Montecito as the Thomas fire burns.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 47/73

Carpenteria resident Chris Gayner, right, photographs a plane in the hills of Carpenteria.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 48/73

From left, residents Michael Desjardins, his neighbor Patty Rodriguez, daughter Mikayla, wife Veronica, mother in law Amanda Buzin, and son Mikey keep an eye on the Thomas fire in Carpenteria.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 49/73

Mary McEwen cheers as she sees fire crews make their way up a hill past her home on Toro Canyon Rd. in Montecito.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 50/73

Dan Bellaart and wife Mary McEwen comfort each other in the backyard of their home that includes an avocado ranch on 9 acres of land on Toro Canyon Road in Montecito, as the Thomas fire burns in the background.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 51/73

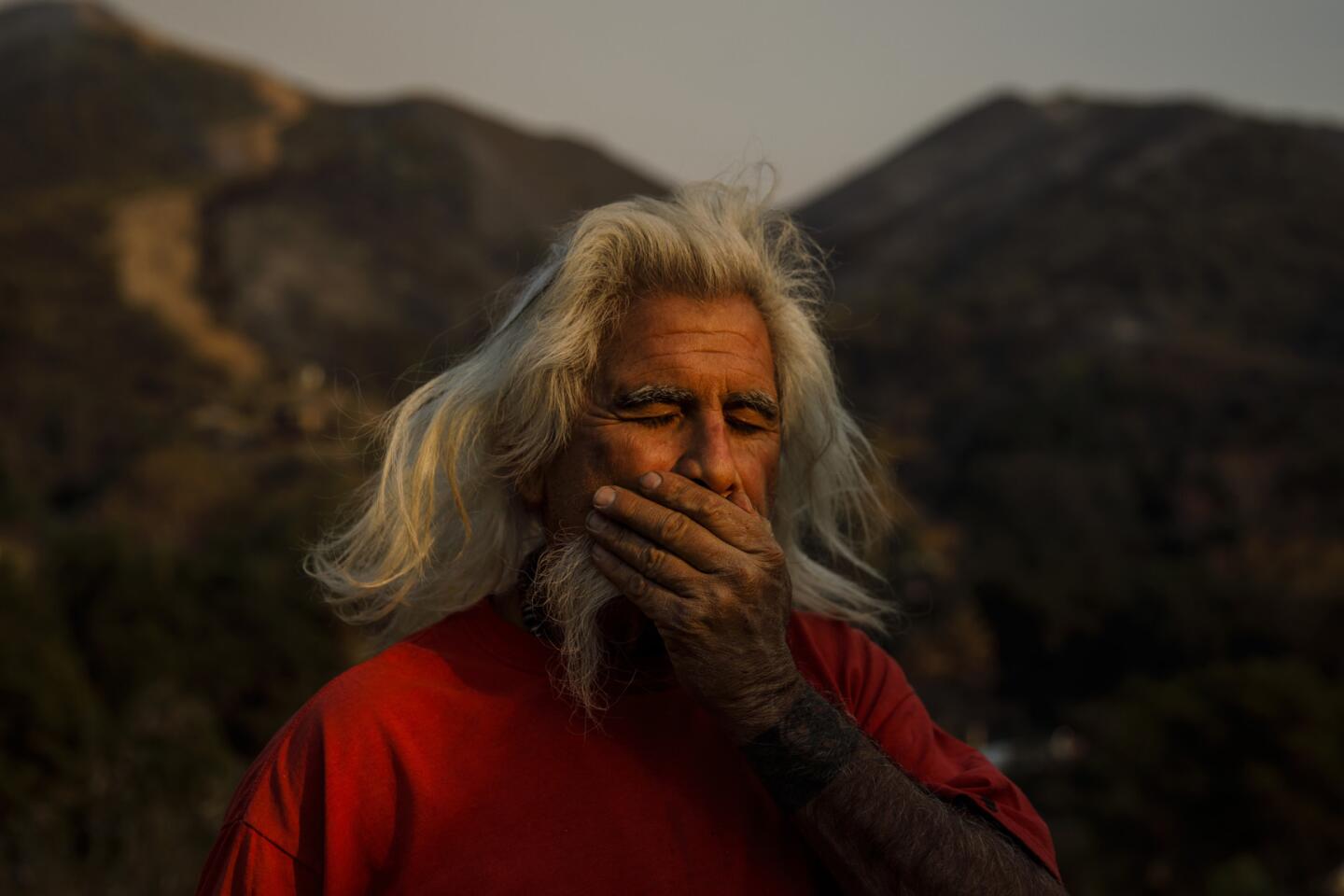

Carpinteria resident Jay Molnar, 55, mouth and nose protected against the smoke, views flames glowing in the hills above the city on Dec. 11, 2017.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times) 52/73

Sacramento firefighters battle a blaze in Toro Canyon in Carpenteria at dusk Tuesday.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 53/73

Josh Acosta, superintendent with Fulton Hotshots looks for ways to fight fire consuming a structure threatening two homes high up Toro Canyon in Carpenteria at dusk Tuesday.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 54/73

A motorcade passes on tHighway 126 carrying the body of a Cal Fire engineer Cory Iverson, who died Thursday morning while battling the Thomas Fire.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 55/73

Santa Paula City officials, Police and Firefighters salute from a bridge as a motorcade passes on the Santa Paula Freeway 126 carrying the body of a Cal Fire engineer Cory Iverson.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 56/73

Forest Service crews cut and clear dense brush for contingency lines off of East Camino Cielo in the Santa Ynez Mountains above Montecito and Santa Barbara to help stop the Thomas fire from advancing.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 57/73

A hotshot crew from Ojai marches towards their assignment to protect structures on East Mountain Drive in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 58/73

Firefighters monitor the flames Saturday from a staging area near Parma Park in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 59/73

Flames slowly make their way down a valley behind a home in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 60/73

Flames whip around power lines as they move through Sycamore Canyon on Saturday, threatening structures in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 61/73

Smoke billows over Santa Barbara as the Thomas Fire continues to threaten the area on Saturday.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 62/73

Bill Shubin, deputy fire chief of the Santa Rosa Fire Department checks on flames burning near homes north of East Mountain Drive in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 63/73

A fire truck pulls responds to fires burning near homes on East Mountain Drive in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times ) 64/73

Brian Good, from US Forest Service, leans forward against the wind, and holds up a Kestrel to measure wind speeds up to 50 mph on Gibraltar Road in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 65/73

A plume of smoke moves south as winds as high as 50 mph blow down Gibraltar Road on the west fork of Cold Spring Trail in Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 66/73

Flames and a big plume of smoke threaten homes on Gibraltar Road near Gibraltar Rock, outside Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 67/73

The sun rises as fire crews prepare for another day of fighting the Thomas Fire, in Montecito, Calif., on Sunday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 68/73

An aircraft makes a water drop over a hot spot up in the mountain range at Gibraltar Rock near Montecito, Calif. on Sunday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 69/73

Humboldt County firefighters Bobby Gray, left, hoses down smoldering flames inside a destroyed home, as Kellee Stoehr, right looks on, after the Thomas Fire burned in Montecito, Calif. on Sunday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 70/73

A home on Park Hill Lane was destroyed by the Thomas fire in Montecito, Calif.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times ) 71/73

Humboldt County firefighters Lonnie Risling, left, and Jimmy McHaffie, right, spray down smoldering fire underneath the rubble of a home that was destroyed by the Thomas Fire, in Montecito, Calif., Sunday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 72/73

Fire crews help the Behrman family retrieve their family’s personal belongings out of their burned home, in Montecito, Calif., on Sunday.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 73/73

In the foreground of the ridges that were burned by the Thomas Fire, Rusty Smith stands outside his home that survived the flames that were kicked up by Saturday’s wind event and threatened his home in Flores Flats on Gibraltar Road, near Montecito.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) Some 20 miles west, as the Thomas fire closed in on Carpinteria, dozens of people crowded an evacuation center opened at UC Santa Barbara. Men, women and children had been trickling in since 2:30 a.m. They slept in cots sprinkled across the university gym floor. A father played pingpong with his son nearby.

Meanwhile, ash and silence blanketed the beach community of Summerland. The quaint eateries, coffee shops and wine shops along Lillie Drive were closed or empty. Residents walked their dogs and checked the daily fire map posted on a board outside the fire station.

Up along State Route 192, Laurent Pellerin wore a surgical mask as he packed his red Audi station wagon with winter clothes and snow chains.

The 48-year-old home decor store manager was getting ready to drive his family to Chicago for a new job when the fire closed in on his cottage near Toro Canyon over the weekend. Now they are leaving, unsure if their home will survive after they go.

“It is surreal,” he said. “We are leaving the fires and rushing to get the snow chains for winter.”

About 7,000 firefighters from 11 western states have poured into Ventura and Santa Barbara counties to try to contain the Thomas fire. Firefighting efforts have cost about $48 million.

In the last week, helicopter crews alone have dumped 1.7 million gallons of water on the blaze. That’s enough water to fill roughly 70 backyard pools.

While Monday’s slow growth left firefighters hopeful, a red flag warning, indicating extreme fire danger, was extended in the region.

“Our vigilance in this is still equally as high,” Ventura County Fire’s Swindle said.

Serna and Panzar reported from Montecito, Tchekmedyian from Los Angeles. Times staff writer Brittny Mejia contributed to this report.

joseph.serna@latimes.com

alene.tchekmedyian@latimes.com

javier.panzar@latimes.com

ALSO

Winds, terrain and fuel: Why the Thomas fire has been difficult to contain

Woman accused of looting home affected by San Diego wildfire

The inferno that won’t die: How the Thomas fire became a monster