State agency slow to protect public from toxic waste

One summer Saturday in the Bay Area city of Richmond, nitric acid leaked from a tank at a metal plating company, forming a toxic cloud that floated over a neighborhood of small houses and stucco apartments.

“People were coughing. They were gasping for air,” recalled Denny Larson, a community organizer who rushed to the scene. More than 125 people were taken to hospitals.

The year was 1992.

Four years later, state regulators decided a study was needed to assess the extent of contamination from that and other releases of hazardous materials at Electro-Forming Co. Seven more years passed before the Department of Toxic Substances Control began the assessment.

All the while, the company continued operating, even as signs of danger accumulated. A former employee told authorities toxic waste had been poured into a laundry sink. This year, state inspectors found cyanide stored near containers of acid; if the two were mixed accidentally, the resulting gas could kill workers and neighborhood residents.

The state obtained a court order forcing Electro-Forming to dispose of the cyanide safely. But the wider study of contamination at the site still has not been completed—more than 20 years after the nitric acid spill panicked the neighborhood.

The Department of Toxic Substances Control is supposed to use regulations, fines and the threat of legal action to protect Californians and the environment. But its oversight of hazardous waste operations — and its response to urgent problems — are often ineffectual and glacially slow.

This conclusion emerges from a Los Angeles Times review of departmental inspection reports, internal memos, court records and local fire and health department documents, as well as from interviews with residents, business owners and regulators.

The review found that:

•A quarter of California’s 118 major hazardous waste facilities are operating on expired permits that may not meet current standards. In a conspicuous case, a battery recycler in Vernon whose lead and arsenic emissions have endangered the health of residents in southeast Los Angeles County has been smelting batteries for decades with only a temporary permit.

•Hundreds of companies have walked away from contaminated sites, sticking taxpayers with cleanup costs. The department acknowledges that it did not even try to collect $140 million in such costs from 1987 through last year.

In cases where the department did make some effort to recover cleanup costs, it folded when polluters simply failed to pay bills totaling about $45 million.

•Increasingly, regulators have not used their strongest legal weapons to bring polluters to heel. In a state where more than 100,000 businesses generate hazardous waste, the department has referred an average of four cases per year to prosecutors over the last five years – compared with more than 40 a year in the previous five-year period.

•The agency’s use of financial penalties has also declined. From 2008 through 2012, companies agreed to pay fines totaling $2.45 million a year on average. That’s half the average of the previous five years.

“There is a systemic problem with enforcement of regulations to protect the public,” said state Sen. Kevin de Leon (D-Los Angeles), whose district includes Vernon, parts of the Alameda Corridor and other communities affected by hazardous waste operations. “It’s the agency’s main responsibility to ensure that these facilities pose no harm, and the reality is, that is not happening.”

Agency in turmoil

The causes of the breakdown include inconsistent standards for regulation, haphazard enforcement, years of staff cuts and turnover at the top. The agency has had seven directors in the last 10 years.

“When I came on board, I found a department that was [in] what I would call structural disarray,” current director Debbie Raphael said at a recent public meeting. “We had all sorts of problems with our budget... with our staffing. … There was a lot of turmoil.”

Raphael, who took over in 2011, declined to be interviewed for this article. Previously, she has said she’s working hard to correct a long list of inherited problems.

“We are committed to owning up to the problems and taking the steps necessary to ensuring they are fixed once and for all,” she said in a statement posted on the agency’s website.

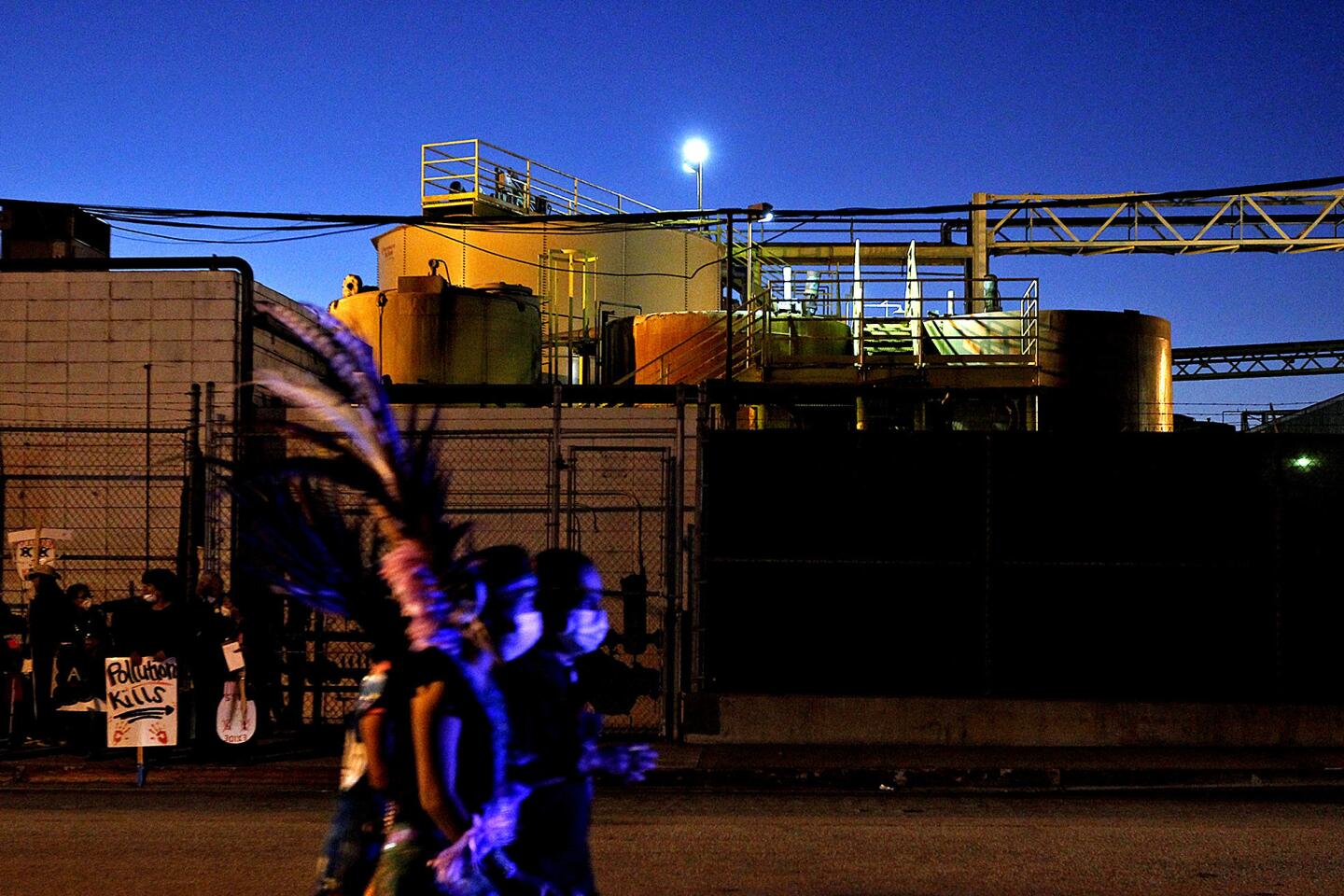

The department’s often disjointed approach to oversight came into sharp relief this year in Vernon, where Exide Technologies, one of the world’s largest makers and recyclers of lead-acid batteries, operates a smelter.

In March, the South Coast Air Quality Management District reported that arsenic emissions from the plant created an elevated risk of cancer for as many as 110,000 people in an area stretching from Boyle Heights to Huntington Park. The district has cited the plant 41 times since 2003, often for excessive lead emissions. Exide took over the operation in 2000.

For decades, the Department of Toxic Substances Control has allowed the plant to operate without the full permit required by federal law. Instead, it has run on “interim status,” a temporary designation intended to give companies time to qualify for permits and meet legal standards for safe handling and disposal of toxic materials.

In 1992, soon after the state agency was founded, environmental activists flew to Sacramento and appealed to top officials to make sure the battery plant and similar facilities obtained permits.

One by one, other facilities did.

Not Exide.

“How is that possible?” asked Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics, a nonprofit her mother helped found in 1989. “It’s not like it’s some small mom-and-pop facility that we have somehow missed ... Their smokestack can be seen from downtown L.A.”

In an interview in October, Raphael called the department’s record on Exide “an embarrassment.”

Jim Marxen, the agency’s top spokesman, said last week that regulators do not have a good explanation for the plant’s continued operation without a full permit.

“I don’t blame the activists who say we are slow to act,” he said. “If that was in my neighborhood, I would say the same thing. ... Ten years ago, when they had hearings on this, there was frustration even then.”

After The Times published articles in the spring about the plant’s arsenic emissions, the department ordered Exide to suspend operations. Exide appealed in Los Angeles County Superior Court. The company said it had reduced the emissions by 70% since 2010 and that the plant posed “no substantial danger to the public health, safety or the environment.”

Judge Luis A. Lavin allowed the facility to reopen, pending the outcome of an administrative hearing on the suspension order.

Ultimately, the department reached an agreement with Exide, requiring the company to set aside $7.7 million to replace leaking wastewater pipes and further reduce its arsenic emissions. It was also required to offer blood tests to 250,000 people who might have been affected by the emissions.

In return, state officials dropped their effort to shut the plant. The air district, however, is still seeking to close the facility until Exide shows that it can consistently keep toxic emissions within safe limits.

Exide officials are fighting the air district’s effort but say they are cooperating with the Department of Toxic Substances Control.

“The department has unfortunately had a long history of constant turnover and uncertain standards — a situation that has left permittees frustrated with frequently shifting oversight, guidance, requirements and deadlines,” said Bud Desart, a senior director of Exide’s recycling group.

He added, however, that Exide officials are working with the “new and engaged leadership now at the department” to overcome “historic challenges” and obtain a permanent permit.

Though Exide is the only major hazardous waste facility in California that has never acquired a full permit, 29 others are running on expired permits.

A report by CPS HR Consulting, a Sacramento firm hired by Raphael, said the situation stemmed in part from “poor management practices” and the lack of agreed-on procedures for revoking or denying permits, even in response to significant threat to public health.

Liza Tucker, a staff member at Santa Monica-based Consumer Watchdog, said the department has often lacked the will to force companies to make changes to their operations.

“They buy the line that companies won’t be willing to do business in California if the agency is too tough on them,” said Tucker, who specializes in environmental issues. “They’re willing to sacrifice public health for the sake of jobs, but they shouldn’t be mutually exclusive.”

While some other states renew permits within 180 days, the CPS report said, California takes years — sometimes more than a decade. Companies are allowed to keep operating in the meantime as long as they have applied for new permits.

Unbilled cleanup costs

One of the agency’s most embarrassing lapses was its failure to recover $184.5 million in cleanup costs stemming from 1,825 polluted sites — in many cases because it failed to send a bill.

Many of the polluters were small, bankrupt operations, but the list of those never billed includes profitable businesses and corporate giants such as Chevron and PG&E.

Raphael herself disclosed the problem in May. She said she would make “every effort to collect past costs” and that the department had instituted a new billing procedure and stepped up collection efforts. So far it has recouped about $16 million.

PG&E officials learned from news reports that the company had never been billed for $85,000 spent to clean a number of sites it owned. The utility contacted the department, asked to be billed and paid immediately, PG&E spokesman Jeff Smith said.

Chevron was never billed for $53,000 in cleanup costs, according to state records. The company declined to comment.

The largest amount outstanding is from Chemical & Pigment Co., a Contra Costa County business that abandoned a heavily contaminated 12-acre site more than a decade ago. The state has spent more than $9.4 million to clean it up, and the project is not finished.

The company produced zinc sulfate for fertilizers and other products and had a history of groundwater pollution and other environmental problems, records show. In 1996, it was acquired by Robert G. Knox III, a former Alameda County treasurer and supervisor, and his CPC Holdings Inc.

In March 1998, state regulators fined the company $50,000. Two months later, Chemical & Pigment filed for bankruptcy protection. When the state rejected its clean-up plan, the company liquidated its assets and walked away.

Knox said that when he took over the operation, he believed it was economically viable and that its environmental issues, centered on a 15,000-cubic-yard pile of contaminated soil left by a previous owner, could be fixed.

But state regulators, he said, were “unrealistic about the fact that this was a small company that didn’t have the resources to do the cleanup at the pace they probably wanted.” The company abandoned the property at the direction of the bankruptcy trustee, Knox said.

Among other things, it left behind 75 “super-sacks” containing one cubic yard each of zinc sulfate, with high concentrations of cadmium and lead. Also abandoned were leaky storage tanks holding thousands of gallons of dangerous chemical mixtures and the soil pile contaminated with zinc, cadmium and lead, the state said in a 2002 report.

When Knox and previous occupants didn’t heed the agency’s cleanup order, the department began the work itself.

The state has placed liens on the property, which would allow it to recover costs in the event of a sale.

Other than lien notices, Knox said, the state made no attempt to recover costs.

“I never heard from them again,” he said in early December.

The department said last week it is “still investigating the feasibility” of recouping cleanup expenses associated with the site.

Marxen attributed the broader failure to recover costs to a “systematic breakdown” caused by a lack of “resources, training and will.”

Not trying is no longer an option, he said: “The attitude has got to be to go after everybody until every avenue has been exhausted.”

State officials said they also plan to increase criminal enforcement actions. Earlier this year, personnel cuts had trimmed the agency’s criminal investigations staff to 12, with only one in Southern California.

In the last six months, the department has added two investigators in Southern California and will soon add a third.

A lack of action

In the Electro-Forming case, politicians and environmental activists were mystified by the department’s lack of forceful action after the 1992 nitric acid spill in Richmond.

A memo in the department’s files indicates that in January 1996, staff members recommended a “preliminary endangerment assessment” of the property. It wasn’t begun until seven years later.

Marxen said regulators were dealing with more pressing situations at the time, such as the closure of military bases and the notorious Stringfellow acid pits, a federal Superfund site in Riverside County.

In 1993 and again in 2002, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reviewed the site for possible inclusion in the Superfund clean-up program, but decided both times that the risks it posed were not sufficiently urgent.

Shortly after the 2002 review, state officials turned their attention back to Electro-Forming. The owner, Gerhard Patigler, had pleaded guilty that year to criminal charges of improperly storing hazardous waste from a metal-plating shop he owned in Alameda County.

In 2003, the department conducted the “preliminary endangerment assessment” and found a host of problems, including dangerous levels of chromium in the soil.

Four years later, the agency determined that the contamination was an “imminent and substantial endangerment” to people living nearby, and ordered Electro-Forming to devise a cleanup plan.

The case took a bizarre turn in 2009, when Patigler flew a small plane into the Arctic and was never heard from again.

His daughter Marion, who now runs the company, asked to put the site investigation on hold to sort out her father’s estate. State officials granted her request, but since 2011 they have pressed the company to work on a clean-up plan.

Last year, a former employee told authorities that his duties included driving drums of hazardous waste to Marion’s home in Pinole and pouring the contents into her laundry sink, according to Contra Costa County records and a civil complaint filed by the department.

The ex-employee also said Electro-Forming workers emptied part of a 6,900-gallon tank containing cyanide onto the ground at the plant.

Patigler did not return a call seeking comment. Her lawyer denied the former employee’s allegations and said the man manufactured them because he had been fired.

In March of this year, investigators searched the site and were alarmed to discover a drum of cyanide near a drum of acid, according to the department’s civil complaint. If an accident caused the two substances to mix, a deadly gas could form.

Still, agency officials didn’t seek an emergency order to shut down the company. Instead, they filed a lawsuit seeking fines and an order barring Marion Patigler from handling or disposing of hazardous waste without court approval. The case is pending.

In November, officials obtained a judge’s order forcing the removal of the cyanide. The state and a consultant for the company are devising a plan to clean up the broader contamination, which investigators now believe may be tainting groundwater.

Assemblywoman Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), whose district includes neighborhoods near the plant, said she is astonished at how long the situation has dragged on.

“These serious violations go back 20 years,” she said. “You’ve got to question the effectiveness of our regulatory system if a company like this persists with these kinds of violations.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.