Tribes, firefighters cooperate to save sacred sites

They were bleary-eyed from lack of sleep as they converged high in the San Bernardino Mountains at twilight.

While two lightning-ignited fires barreled toward Big Bear Lake last summer, the fire marshal and the Indian tribe member discussed their options on how to preserve ancient artifacts and still protect the community.

“We got knowledge there were ‘dozer lines that went through and uncovered an archeological site,” said James Ramos, cultural resource coordinator for the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. “It’s real important to preserve the culture because it’s really part of the history of the whole area.”

The early-morning meeting with San Bernardino County Fire Marshal Peter Brierty is emblematic of a burgeoning relationship between firefighters and Indian tribes, whose ancient burial grounds and ceremonial sites are often on land prone to wildfire.

In the past, tribal representatives were left in the dark about firefighting operations and fire officials had little clue of the historical significance of ancient sites threatened. Firefighters have bulldozed lines through terrain, unwittingly destroying sacred Indian burial sites, ceremonial grounds and villages.

Tribe members now attend fire safety classes in hopes of helping bulldozers avoid sacred sites. Fire officials and archeologists say the cooperation has allowed them to protect artifacts on almost every major wildfire in the last few years.

That rapport was on display during a blaze last month that scorched U.S. 395 in Kern County and threatened sacred sites belonging to Paiute and Shoshone tribes. Archeologists and the tribes worked together to steer the blaze and bulldozers away from them.

“People are realizing that if we plan ahead we should be able to protect these resources,” said Larry Myers, executive secretary of the Native American Heritage Commission, the state agency responsible for identifying and cataloging Native American cultural resources. “How important would it be to non-Indians if you bulldozed over a cemetery?”

Britt Wilson, cultural resources director for the Morongo Band of Mission Indians, was one of about a dozen tribe members at a recent fire training class in San Bernardino.

During the good-humored session — “There’s more chiefs here than Indians,” quipped one attendee of all the fire chiefs present — they learned how wildfires behave and practiced deploying protective shelters.

“We aren’t going to put them on the fire line, but we want to work with them to make sure we preserve these resources,” Brierty said. “We’ll call them out when we get the fire so we are working together as a team.”

Both sides say the relationship is crucial as the fire threat in California deepens.

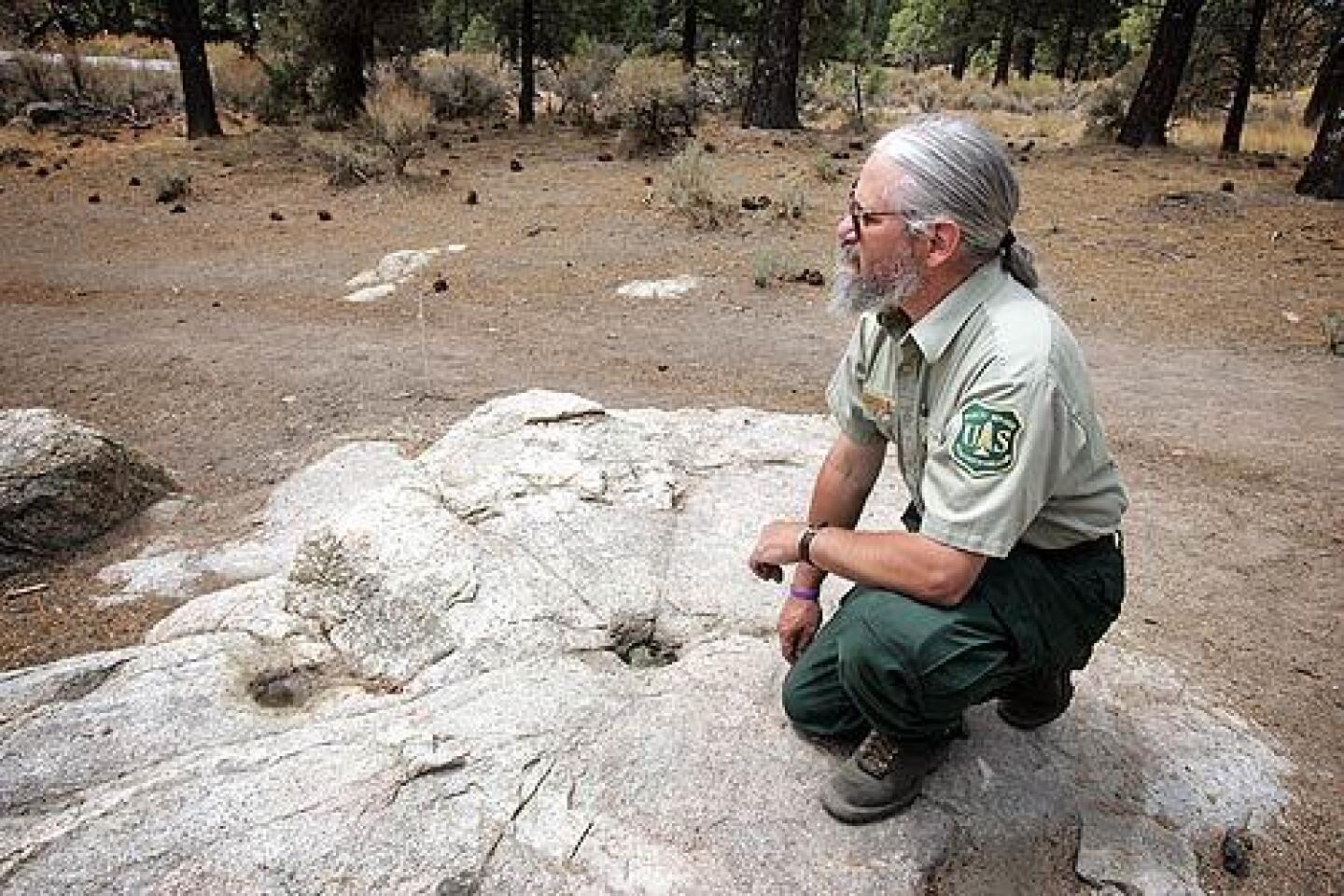

“Every individual site is an endangered species of its own,” said Doug McKay, a U.S. Forest Service archeologist. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone. You can’t re-create [artifacts from] an 8,000-year-old village.”

Once the sites are located, they become “our most closely guarded secrets,” said Forest Service spokesman John Miller. Grave robbers and treasure hunters are always a concern. After the Southern California wildfires in 2003, a rash of Indian artifacts thought to have come from scorched areas appeared on EBay.

For Brierty, keeping the locations cloaked is a priority for professional and personal reasons: His wife, Ann, belongs to the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

“I don’t think it would be any different than protecting a Catholic church or Jewish temple from a fire,” he said.

The National Historic Preservation Act requires that tribes be contacted when historic sites are threatened by disaster. But fire officials often don’t know the location of artifacts, and tribes were either reluctant to disclose them to outsiders or had lost track of them through the years.

A 2002 fire that charred 50 square miles in the mountains of San Diego County altered both dynamics.

Bulldozers that cleared fire lines tore through several sites thought to belong to an 8,000-year-old culture. Indian representatives denounced the razing, while fire officials saw the need for a change in policy.

Linda Pollack, lead archeologist for California Department of Forestry & Fire Protection’s southern region, was among those charged with building a bond to benefit both sides.

For the last dozen years, Pollack has sifted through the hardpan earth in search of ancient sites in need of preservation. She started visiting tribes, explaining who she was, her knowledge of the lands and what she hoped to do.

She gradually proved herself trustworthy. Tribal officials now often call her before she can reach them.

“They’ll give us bits and pieces of information to start, and the more they realize we aren’t publicizing or posting it all over the place, the more information they give,” Pollack said.

Even misguided diligence can pay off. At a fire in the San Bernardino Mountains, Pollack recalled, a young firefighter was elated over what he thought was a significant archeological find.

“It was actually a water ditch about 6 inches wide,” Pollack said. “But in searching that, we found a large ceremonial house that was a Native American structure nearby.”

--

jonathan.abrams@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.