Zookeepers attempt tough balancing act

It was any zoo’s worst nightmare.

Shortly after 5 p.m. on Christmas Day, San Francisco Zoo Director Manuel Mollinedo received a call at home: Tigers are on the loose and somebody may have been hurt.

“At first I thought it was a practical or sick joke,” he recalled in an interview. “But I took it seriously and grabbed my jacket and got in the car and drove to the zoo.”

Soon, the gravity of the situation became all too clear. A Siberian tiger had somehow vaulted from her enclosure, fatally mauling 17-year-old Carlos Sousa Jr. and injuring his two friends.

But other circumstances intensified the horror. The escape took place shortly before dark in a park laced with curving paths and thick stands of foliage. And there was no public address system to alert the few patrons meandering through the zoo.

A placid holiday afternoon had turned frightening and chaotic, with officers uncertain of such basic facts as how many tigers were on the loose. By the time order was restored, the entire zoo had been declared a crime scene and the institution had earned the grim distinction of being the first accredited zoo in the United States in which a visitor was killed by an escaped animal.

“It was almost surreal, the tragedy and emotions that overwhelmed me,” Mollinedo said. “It boggled my mind, and my staff was shellshocked.”

The incident cast a harsh light on the balancing act that challenges zookeepers everywhere: Keep visitors -- who can be unpredictable and dangerous -- close to, yet at a safe distance from wild animals, who can be equally unpredictable and dangerous.

Zoos and zoo-goers throughout the U.S. are watching the tragedy closely.

“Many of our members are refreshing themselves on safety procedures, reassuring the public that their zoos are safe,” said Steven Feldman, a spokesman for the Assn. of Zoos and Aquariums, a zoo accrediting body. “When we learn the full set of facts from this incident, we can make judgments about whether changes should be made in San Francisco or elsewhere.”

Much of what happened in San Francisco is still subject to speculation. But investigators are examining the possibility that Sousa and his friends provoked the tiger, a 4-year-old, 350-pound female named Tatiana, which was later fatally shot.

“Police are looking at a 9-inch rock and pine cones and . . . branches or sticks that would not normally be in the tiger’s enclosure,” said Sam Singer, a zoo public relations consultant. “They’re trying to determine how they got there.”

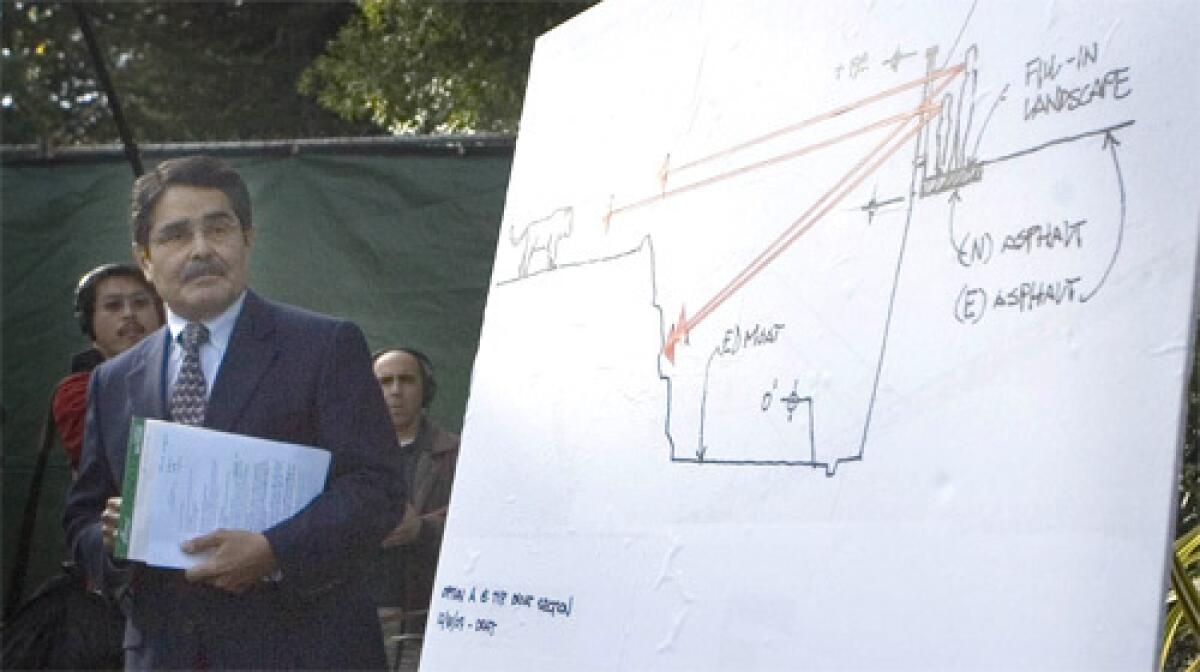

Other possible clues have drawn police attention. A shoe print found on a railing next to the wall of the tiger grotto is being checked against the shoes worn by the three friends. A claw mark was discovered atop the grotto wall, indicating that Tatiana leaped over, a source close to the case said. Stains thought to be blood were discovered on a sign and on foliage between the railing and the wall, the source said.

As part of their criminal investigation, police interviewed the two survivors, as well as a San Francisco woman who said she saw four young men taunting the nearby lions that afternoon.

Mark Geragos, a Los Angeles attorney representing the two brothers who survived the attack, has denied that Tatiana was taunted or provoked in any way. He contends the zoo is orchestrating a smear campaign to divert blame in the incident -- a strategy that could be a preemptive defense against the lawsuits the zoo will almost certainly face.

He also suggested that tigers need no reason to attack. “Has everyone forgotten about Siegfried and Roy?” he asked, referring to the mauling of tiger trainer Roy Horn in 2003.

Even if Tatiana was teased, criminal charges are unlikely, legal experts said.

“You’d have to demonstrate that a reasonable person could foresee that taunting a tiger could result in a death,” said Rory Little, a professor at UC Hastings School of Law in San Francisco. “A reasonable person, though, would assume the tigers in a zoo couldn’t get out. You can go to the zoo any day of the week and see kids taunting animals.”

At zoos across the country, the attack has prompted a second look at safety procedures. In Los Angeles, officials are studying the possibility of adding surveillance cameras.

In San Francisco, the walls of the now-closed big-cat enclosures are being raised from 12 1/2 to 19 feet with panels of thick glass. New signs explaining zoo etiquette -- the equivalent of ‘do not disturb the animals’ -- are being posted throughout the park. A public address system is being installed. And the zoo last week started adding a 3-foot-tall chain-link fence to bring the walls at two separate polar bear exhibits to 16 feet high.

Built in 1940, the big-cat grottoes are fronted by walls more than 3 feet lower than the height recommended by the Assn. of Zoos and Aquariums. Even so, the organization raised no objections about the safety of the areas in a 2004 inspection, according to San Francisco Zoo officials.

Geragos said his investigators have interviewed a former zoo employee who said that sometime in the last five years, a tiger perched atop the wall and had to be coaxed back into the enclosure. He declined to identify the ex-employee.

A zoo spokesman said that “no one at the zoo is familiar with any close calls involving a big cat in the last five years or any instance of a tiger or lion on the edge of the grotto.”

Whether the recommended 16-foot barriers could have prevented Tatiana’s escape is an open question.

Some animal experts say she must have been worked into an adrenaline-fueled rage to bolt in the first place.

“She had to be in a hyperaggressive state,” said Chris Austria, a former animal trainer who worked with tigers at the former Marine World in Vallejo, Calif., and with bears at the San Francisco Zoo. Without some extraordinary stimulus, “it is really unlikely that a 350-pound tiger would jump up 12 1/2 feet and hold on with her paws and pull herself up,” he said.

Animal trainer Diana L. Guerrero said that zoo tigers become desensitized to yelling or verbal taunting but that someone throwing or dangling things into the enclosure could be enough to trigger an escape.

“In the history of zoos, unless an animal is highly motivated to escape, they usually don’t,” said Guerrero, who has been affiliated with zoos in San Francisco, Los Angeles and elsewhere.

But it wasn’t the first accident to occur at a U.S. zoo.

Last February, a jaguar at the Denver Zoo fatally mauled one of his keepers. In 2004, an escaped gorilla at the Dallas Zoo lifted up a toddler with his teeth and attacked three people before being shot to death 40 minutes later.

Still, the zoo association, which includes 182 institutions in the U.S. and Canada, describes zoo-going as a very safe experience. Last year, 157 million people visited the organization’s zoos and aquariums. The tiger attack was the first fatal attack of a zoo patron since the group started accrediting zoos in 1974, officials said.

In San Francisco, Tatiana mauled a zookeeper at feeding time in December 2006. The woman survived and has filed a lawsuit against the zoo.

Before Sousa’s death, the San Francisco Zoo’s biggest recent controversy centered on its elephants. After two of them died within weeks of each other in 2004, and under pressure from county supervisors, the zoo placed its remaining elephants in a sanctuary.

The move was welcomed by animal welfare groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, which opposes keeping wild animals in captivity. In light of the attacks, the group is urging the zoo to phase out its big-cat exhibits.

On the other hand, keeping tigers in zoos promotes conservation and education, said Feldman, the zoo association’s spokesman. If visitors never got to see an elephant or a tiger, “chances are they would not have that sense of awe and wonder,” he said, “and not be inspired to take action.”

Of the 258 tigers in zoos accredited by the association, only five were born in the wild, he said. Four were captured after killing livestock and were going to be destroyed. The fifth was the cub of a tiger killed by poachers.

Mollinedo, the San Francisco Zoo director, has been tight-lipped about details of the attacks, pointing out that a police investigation and an internal review are ongoing. However, he and police officials have said there was no evidence anyone aided the escape, either deliberately or inadvertently.

“We have not been able to find any witnesses that actually saw what occurred out there,” Mollinedo said. But, he added, “Something provoked that tiger to leap out. I don’t think that tiger would have come out of there if something had not agitated it.”

Mollinedo, 61, has been on the defensive, at one point having to correct information he gave that overstated the height of the grotto walls. Questions also were raised about a police dispatch log, which showed that showed zoo employees temporarily barred police from entering one of the zoo gates.

The official said the tiger had been sighted in the area and his employees were following protocol by keeping the gate closed.

Mollinedo said his staff conducts regular drills for responding to escapes, and the shooting unit practices monthly at a firing range.

He said his staff “performed heroically.” One employee rushed to the tiger grotto and guarded Sousa’s body with a shotgun to protect it from further attack, Mollinedo said.

Mollinedo has weathered his share of zoo challenges.

A Los Angeles native who grew up in Boyle Heights, Mollinedo was a city parks official when he was selected to lead the Los Angeles Zoo in 1995.

When he took the reins, the zoo was beset with aging exhibits and maintenance problems. The animals’ safety was also an issue, with coyotes stealing in and killing several flamingos.

A year into his tenure, Mollinedo won high marks for improving conditions, and the zoo passed its accreditation review.

He proved himself a deft handler of politicians, eccentric donors and celebrities.

“I think he understood the politics of L.A. and the needs of the zoo, and did a lot to stabilize it,” said David Towne, a director of several zoos and one of three members on a committee that evaluated the L.A. Zoo before and during Mollinedo’s tenure.

To be sure, there were rough spots. After a Komodo dragon bit the foot of actress Sharon Stone’s then-husband, San Francisco newspaper editor Phil Bronstein, during a VIP tour, Mollinedo restricted the up-close visits that had raised funds and visibility for his zoo.

Sometimes criticized by staff members for ignoring their advice, he dealt with a number of escapes, none of which caused injury to other animals or people.

Mollinedo left the L.A. Zoo in 2002 to run the city’s Department of Recreation and Parks. He left there to lead the San Francisco Zoo in 2004.

In 2003 the U.S. Department of Agriculture filed a complaint about 35 animal escapes in the previous five years. The L.A. Zoo agreed to work on the problem.

Towne, who consulted with the zoo on preventing more escapes, characterized 90% of them as not “dangerous to the visiting public.” He said the rate seemed high partly because the zoo was conscientious in its reporting, letting federal authorities know about escapes without being required to do so.

But after several gorilla escapes -- all without injury -- Mollinedo said in 2000, “Every time a gorilla escapes, we raise the walls a little higher. . . . We really need a better, more secure enclosure. It would make it a lot easier for me to sleep at night.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.