From the archive: For teen program’s chief, tough love may have turned criminal

The surprise visit to Alberto Ruiz’s house was swift.

Dress quickly, he was told. You’re going to boot camp.

His parents, worried about his drug use and habit of skipping school, had followed a friend’s advice and called Kelvin McFarland.

Ruiz’s behavior had earned him a spot in McFarland’s Family First Growth Camp in Pasadena, a place with a reputation for breaking gang-bangers and drug addicts and turning them into law-abiding teens.

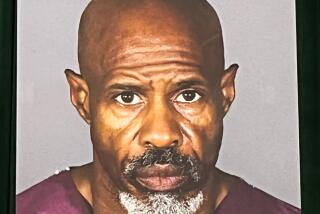

A former Marine who likes to be called “Sgt. Mac,” McFarland founded the camp two years ago and boasted that his tough-love tactics and military-strict discipline were the perfect formula for reforming gang members, taming runaways and getting through to troublemakers.

Ruiz, who is now 18, credits McFarland’s intervention for helping him finish school and quit drugs.

But authorities say McFarland’s scared-straight approach crossed the line and veered into criminal behavior earlier this year when he crossed paths with another Pasadena teen.

Investigators allege that in May, McFarland was driving in Pasadena when he spotted a girl walking along the street during school hours. He stopped to question her, then handcuffed her, placed her in his car and told her to direct him to a relative’s home. At the relative’s home, he demanded money from her father to enroll the 14-year-old in his program. The girl’s father mistook McFarland for a truancy officer when he flashed a badge, Pasadena police said.

McFarland is facing trial on felony charges of kidnapping, extortion, false imprisonment and child abuse, and unlawful use of a badge, a misdemeanor.

Now Pasadena police are investigating possible abuses that allegedly occurred at a rival Pasadena boot camp where McFarland once worked. The Pasadena Star-News recently published videos allegedly filmed in 2009 in which McFarland can be seen yelling at teens, forcing them to gulp down water even as they retch and vomit. In one scene, McFarland and other drill instructors appear to scream at a youngster, inches from his face, as he collapses in tears under the weight of a car tire on his shoulders.

The publicity has had a chilling effect on McFarland’s Family First boot camp. Parents have pulled their kids out in droves. Where several dozen cadets once attended, only a handful remain.

“I’m not going to lie… we don’t have 75 cadets, but we’re still continuing,” said Elpidio Estolas, one of Family First’s directors.

McFarland is quick to defend his work in the community, as is Keith Gibbs, the director of the rival boot camp. Both say they offer a last resort for exasperated parents who have nowhere else to turn.

In interviews with McFarland, his cadets, their families and those who have worked with him, a complex portrait emerges. Critics describe him as a fast talker, easily seducing working-class Latino families with his authority-laden persona. Supporters say McFarland is a man filled with good intentions, who has overcome his flaws such as convictions for DUI and a misdemeanor assault.

McFarland says his criminal history allows him to dissuade cadets from a life of incarceration. He talks openly about the months he was homeless and his continuing struggle with alcoholism. These attributes, he says, make him a relatable figure.

McFarland is set to stand trial Wednesday, though the case has been delayed several times — once after his boot camp could no longer afford to pay his attorney, a former Pasadena mayor. He is now represented by a public defender.

But McFarland continues to operate his program throughout Pasadena, in local parks and occasionally a small strip-mall church.

In fact, it didn’t take long for the boot camp to resume after McFarland got out of jail

In mid-June, from the stage of Faithworks Ministries church, McFarland — freshly released on bail — thanked his cadets and their families, quoting the Bible as he spoke. For days, they had rallied on his behalf outside a Pasadena courthouse, hoping a judge would reduce his bail.

McFarland, a deeply religious man raised by an aunt in rural Georgia, looked on quietly. Dressed in his signature military fatigues, he occasionally barked commands as the cadets stood in formation.

“I don’t know of a boot camp that praises the Lord as much as we do,” said McFarland, who granted The Times access to his boot camp last summer but has since refused to speak with the paper.

After the morning drills, the group moved inside the church. The teens marched single file into a side room for a self-esteem workshop. Their families, meanwhile, sat in the pews, listening to a nutritionist. Involving parents in the program is a key component of success, McFarland says.

“The program has benefited the children tremendously,” said Mirza Balvaneda, who enrolled her son when he was only 8. “The other parents said I was brave to bring him in because he’s so young, but he needed to learn some discipline.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.