For El Cajon’s Chaldeans, an Easter blessing: freedom to worship without fear

Although a devout Christian, Eva Aboona missed the Palm Sunday church services that launched Holy Week on April 9.

But she tried.

At St. Michael’s, one of El Cajon’s two Chaldean Catholic churches, Aboona encountered bumper-to-bumper traffic, a jam-packed parking lot and an overflow crowd of worshipers.

“I couldn’t get in,” she said.

Her husband tried to take the children to Mass at the other Chaldean church, St. Peter’s. No luck.

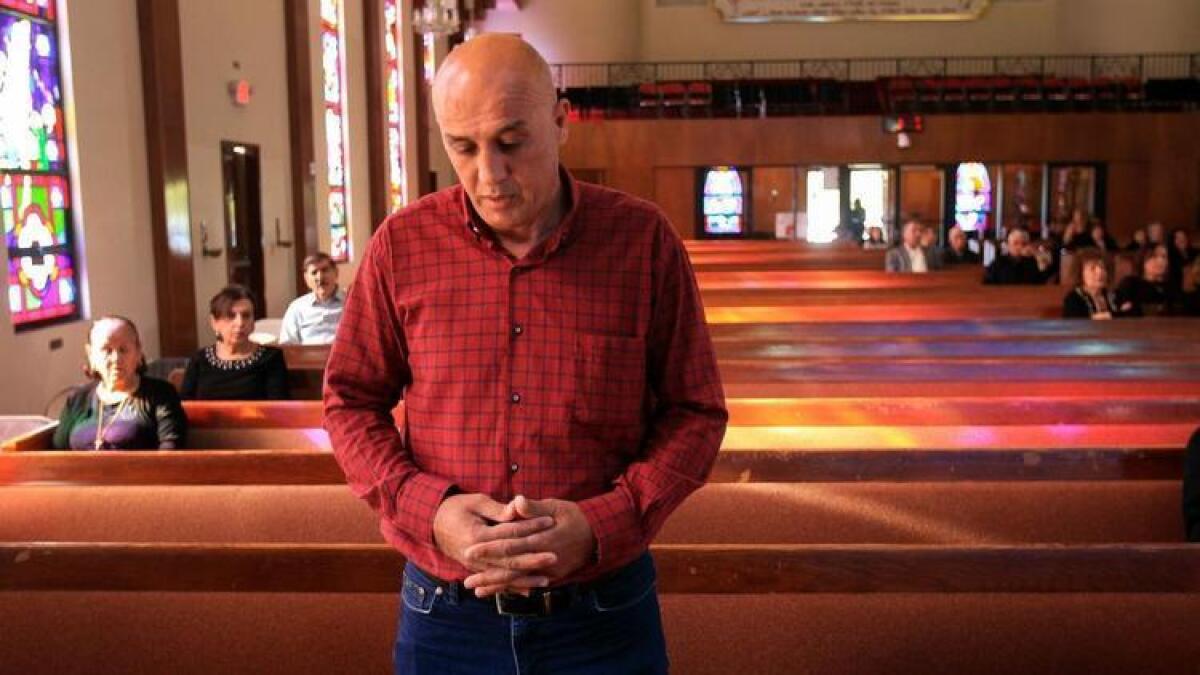

“There was no room to park,” said Raied Aqrawi, 51, through an interpreter. “We had to drive around and go home.”

Lesson learned. For Sunday’s Easter Mass at St. Peter’s, these Iraqi immigrants planned to arrive hours early.

Since landing in the United States on Jan. 10, these Iraqi immigrants have made numerous adjustments. Aqrawi, a chemist and plumber, is seeking work inside and outside those trades. The entire household, including sons Yousif, 14, and Frank, 6, is learning English as fast as possible.

Despite financial worries and language barriers, they are grateful and relieved. That’s especially true as they safely celebrate Easter’s message of renewal and hope.

Four years ago, they celebrated Palm Sunday in their Iraqi village, Alqosh, under threat from nearby ISIS forces. The family fled to Turkey, where their faith was targeted by local officials and neighbors. Last year’s Easter Mass was halted by a bomb.

So while they face struggles in their new home, they cherish the freedom of worship they enjoy here, due to the efforts of local Christians and Jews.

“Here we feel there is law, there is security, there is protection,” Aqrawi said. “Here we don’t have the fear that someone will come to convert us to another religion.”

Among practicing Christians, no week is more significant than the one bookended by Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday. This is true around the world, and certainly among the Chaldeans of El Cajon.

This is a rapidly growing group. There are now 60,000-plus local Chaldeans, double what this population was in 2010. Yet there are only two Chaldean churches, each with room for 700 worshipers.

“The churches are always full, always full,” said Besma Coda, chief operation officer at Chaldean & Middle Eastern Social Services in El Cajon. “We need a new church in El Cajon. There are seven different Masses a day and they are all full.”

That’s seven Masses during ordinary Sundays. For Easter services, there are 12 Masses at St. Peter’s and 10 at St. Michael’s over two days.

“This is the most important week of the year,” said Bishop Bawai Soro, vicar general for the local Chaldean Catholic Diocese. “The whole Christian faith is validated because of the Resurrection of Christ.”

For believers, Holy Week commemorates Jesus Christ’s journey from life to death and back again. Gospels describe his triumphant entry into Jerusalem (Palm Sunday), last supper (Holy Thursday), crucifixion (Good Friday) and final victory over death (Easter). For immigrants escaping persecution, this narrative has powerful echoes.

“It means that God is with us and is with us especially through our dark experiences, our difficult days,” Soro said. “This is what Jesus himself went through when he continued to obey the message of his Father — despite the pain, the suffering. Our faith tells us that whoever believes in the Bible, believes in Jesus and God the Father, will have the same resurrection experience.”

The Holy Week experience, though, is different in San Diego County than in rural Iraq. Aboona was disappointed on Palm Sunday when El Cajon’s streets were not filled with chanting, palm-waving residents as they were in Alqosh.

“Because we don’t live in villages, we live in urban communities,” Soro said, “and you cannot offend your neighbors. There are noise limitations, movement limitations.”

The bishop chuckled. “The reality is that the newcomers will take a few years to adjust themselves to the American lifestyle.”

Already, these adjustments have been coming with staggering speed. Four Easters ago, Aqrawi, Aboona and their children marched past stone buildings to the pealing bells of Alqosh’s ancient monastery. Palm Sunday was a noisy, village-wide affair in this settlement nestled by the mountains near Iraq’s northern border.

On the Nineveh plains below Alqosh, though, Christian settlements had been leveled by ISIS fighters. Women had been raped, men killed, children abducted.

Seeking safety, the family journeyed to Ankara, Turkey’s capital, where they registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. That office found temporary shelter for the family in Amasya.

In that northern Turkish city, they were safe from ISIS but not from religious persecution. Amasya had no Christian churches, and the mayor rejected Chaldean pleas to open one. Yousif quit a part-time job at a barber shop whose owner repeatedly pressured the boy to attend services at the local mosque.

On their first Easter in Turkey, the family conducted their own service behind the closed doors of their apartment.

On their second Easter, a Chaldean priest visited from Detroit, celebrating Mass in a rented hall. Black curtains covered the hall’s windows and police stood outside, ostensibly to protect the Christians within.

The following Easter, last year, was supposed to be a repeat celebration — same priest, same hall, same police cordon. This time, though, the police halted the service and ordered everyone to leave.

There was a bomb outside the hall. The family was almost home when the device detonated.

“We heard it,” Aboona said. “That’s how we knew it was a real bomb.”

Like all refugees, this family went through interviews and background checks by the U.N. and the authorities of their new country — in this case, the U.S. State Department.

They were then routed to El Cajon, because of its existing Chaldean population, and assigned to one of San Diego County’s four resettlement agencies. In this case, that was Jewish Family Service. It’s not unusual for Christian refugees to be referred to this Jewish group, explained Etleva Bejko, the agency’s director of refugee and immigration services.

“We are federally funded for those programs,” she said. “If you participate, you have to serve all refugees regardless of religion.”

Helping needy people of other faiths, Bejko said, is consistent with Jewish values. She quoted Mark Hetfield, president and CEO of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

“He said, ‘We don’t serve refugees because they are Jewish. We serve refugees because we are Jewish.’”

In the current fiscal year, the local Jewish Family Service has helped resettle 232 refugees.

“The majority are Iraqis,” Bejko said.

Like most of those Iraqis, Aqrawi and Aboona and their children were initially overwhelmed by this new culture.

“My personal message to them is, we are their brothers and sisters,” said Bishop Soro, himself an Iraqi refugee who came to the U.S. in 1976. “Every challenge they see here, we were once in their shoes.”

Their life, he predicted, will improve.

“They are the luckiest people in the world,” Soro said. “Despite the fact they have seen difficult days in Iraq, God has rewarded them by bringing them to America, the most blessed country in the world.”

Already, there are signs of assimilation. While there will be no Easter egg hunt for the kids, Yousif and Frank plan to enjoy a customary American activity after Easter Mass.

“They’ve heard there is a Chuck E. Cheese,” said Aqrawi. “So I am taking them to Chuck E. Cheese.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.