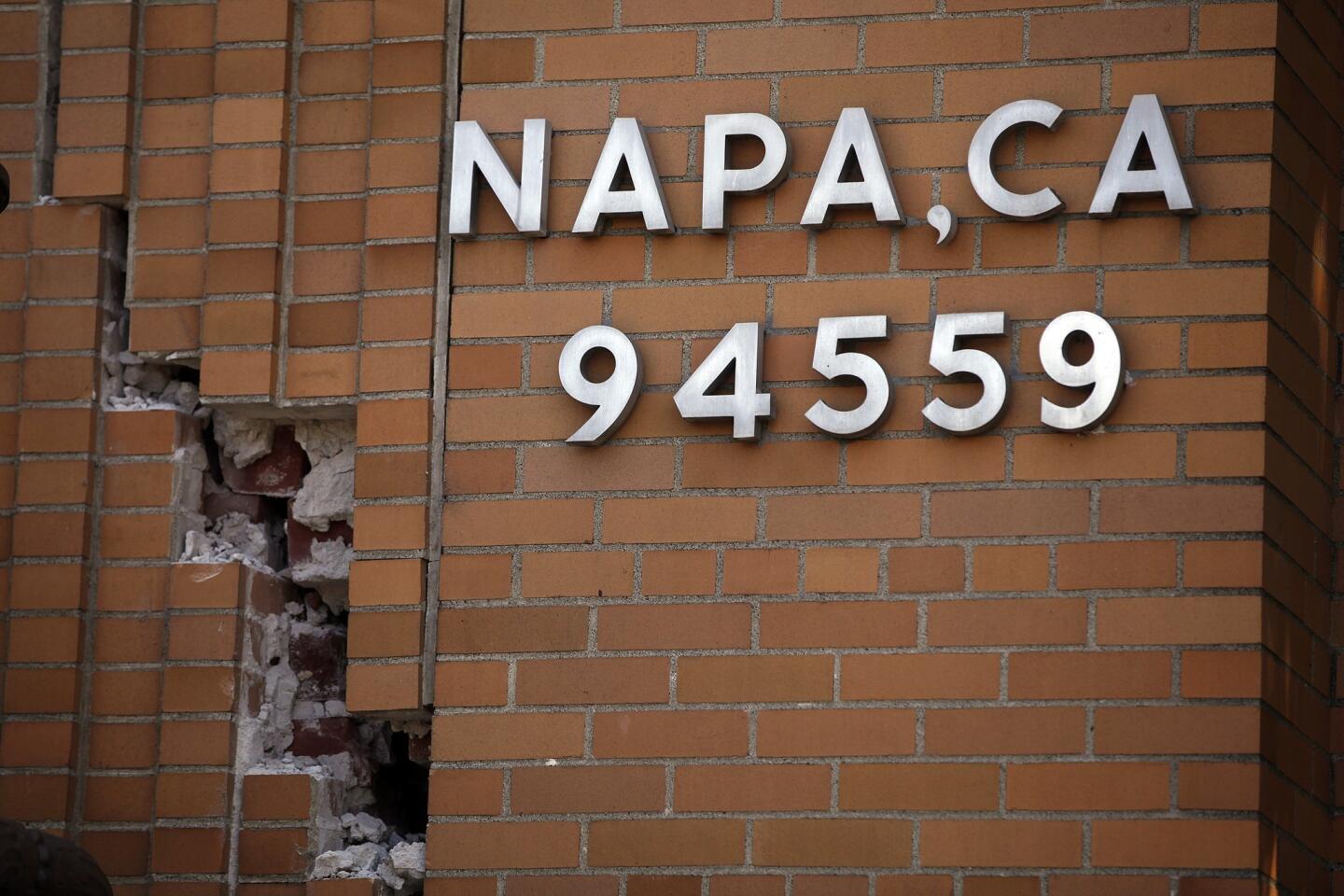

Earthquake leaves Napa wine industry quietly tallying the damage

Oak barrels cracked open and a river of red gushed out. Before long, hundreds of thousands of dollars of wine had coated the concrete floor of Napa Barrel Care, a warehouse near downtown where 40 wineries share storage space.

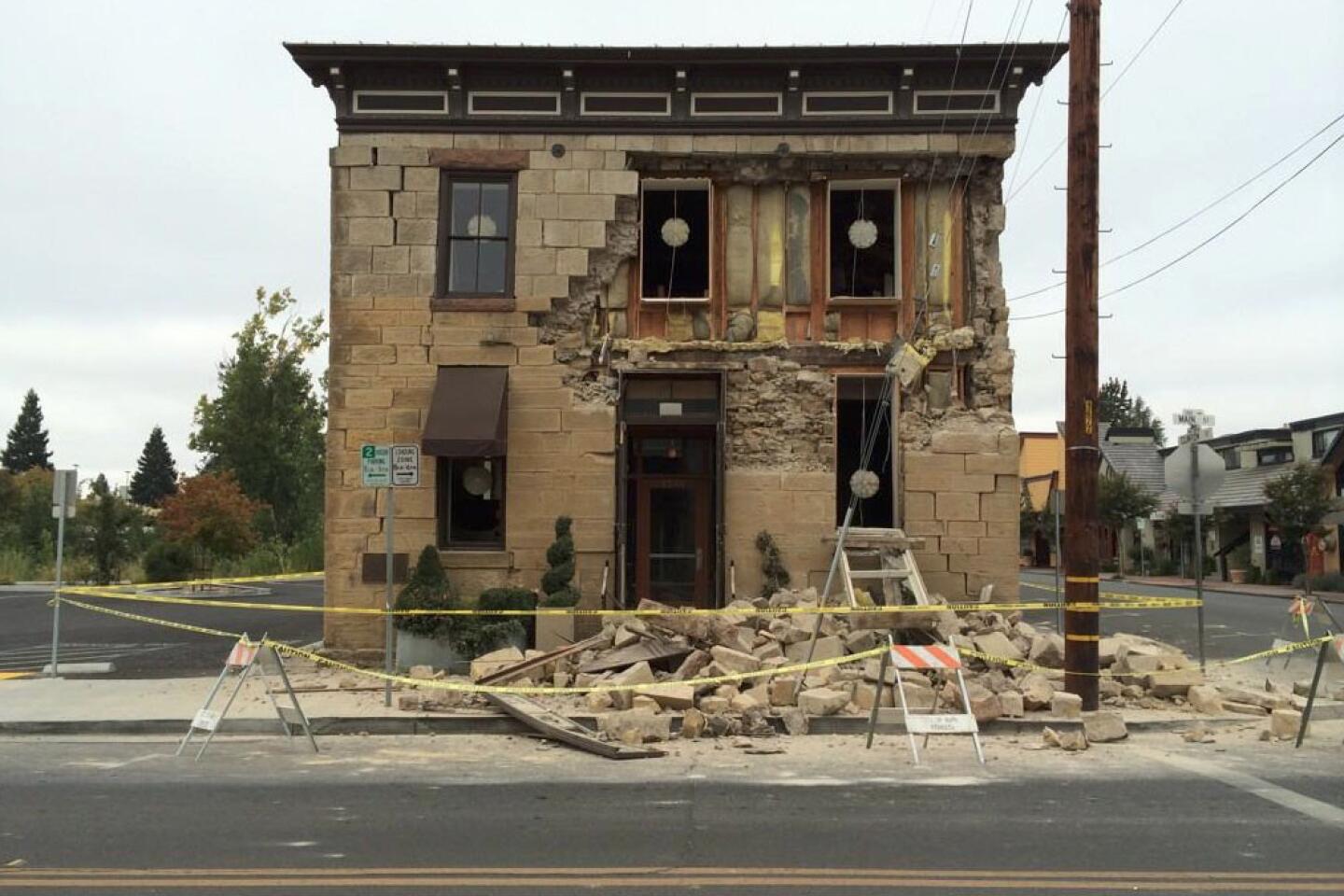

About an hour later and a few miles north on California 29, Hailey Trefethen had just pulled up at the winery her grandparents bought half a century ago. It was still dark outside, but she could make out a silhouette of the old building they use as a tasting room.

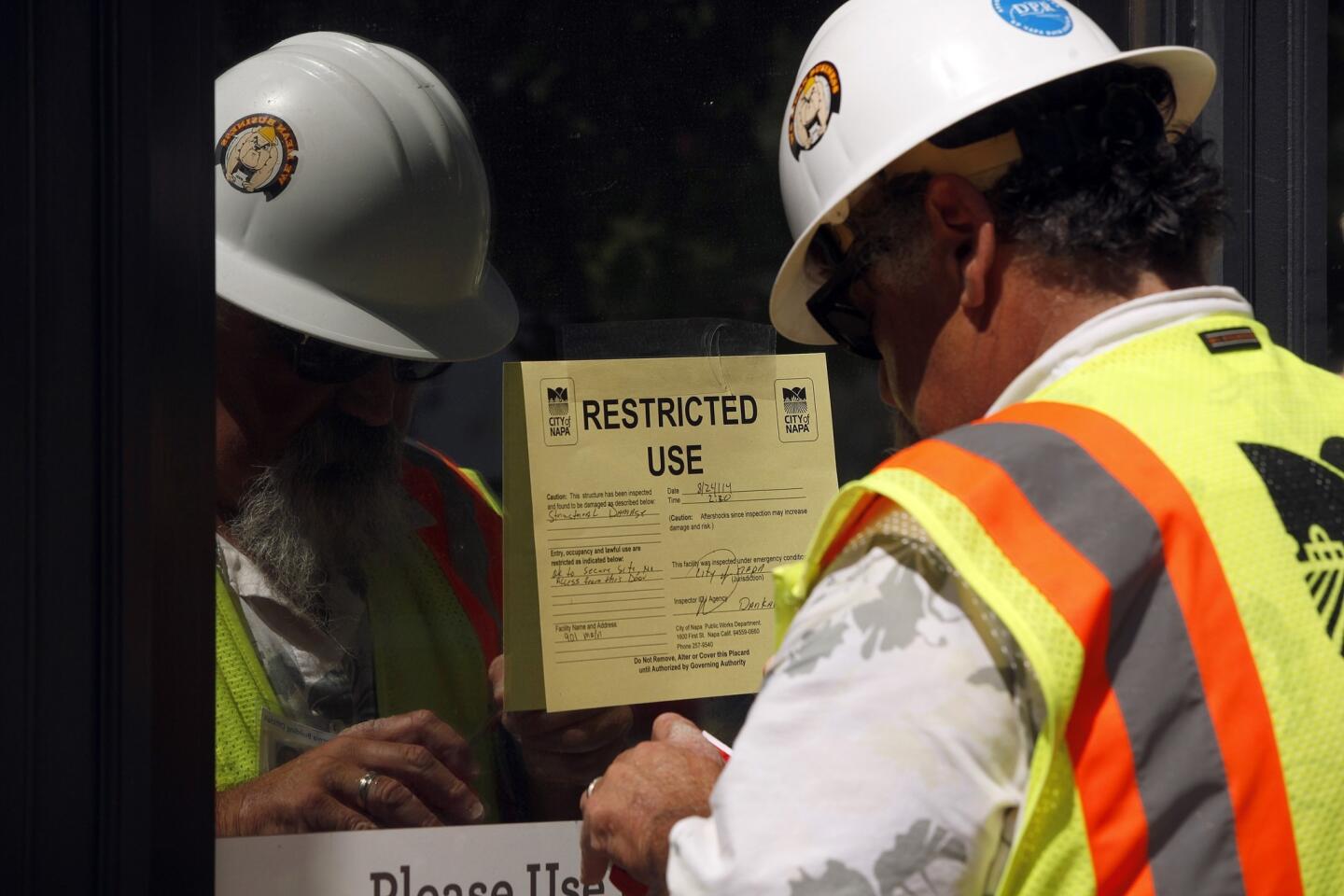

The earthquake’s shaking had pushed the building’s upper stories four feet to the west, creating a precarious-looking structure Trefethen described as Salvador Dali-esque. Now, a small piece of red paper affixed to an outside wall reads, “UNSAFE.”

Since the 6.0-magnitude temblor, more than 100 wineries have reported earthquake damage, according to Napa Valley Vintners, a local trade association. But they’ve maintained a low profile. The few places that have done news interviews have steered clear of damage price tags and anything that could seem like wallowing in their loss. Other places have avoided media coverage altogether.

“A lot of them don’t want their names out there,” said Lewis Perdue, who lives in neighboring Sonoma County and runs a wine-industry trade publication.

Aware of its reputation as an industry of luxury, Perdue said it makes sense that the wine world hasn’t clamored for outside attention.

“It’s like, would Gucci want you to know if their factory flooded?” he said. “The wine world is weird. It’s this, ‘I don’t want you to know about my business’ thing.”

When Napa Valley Vintners, which represents 500 wineries in the area, held a news conference Wednesday, its first since the Aug. 24 earthquake, there wasn’t much talk about the wine industry. Instead, the group announced the creation of the Napa Valley Community Disaster Relief Fund and said it planned to donate $10 million to go toward things like replacing windows at people’s homes, counseling and temporary housing.

But in private, Napa’s wine community rushed to tally its losses and get everything in order before harvest came in a week or so.

The trade association sent out an email asking about damage and created a members-only chat room. Communications manager Cate Conniff said that before long a flurry of posts from vintners began to pop up.

“Members are saying, ‘I need 1,000 gallons of tank space,’ ” she said. “And a few seconds later someone responds, ‘Bring it over now.’ ”

Steven Burgess of Burgess Cellars was one of the vintners who offered help.

The day after the quake, he emailed an employee who oversees wine making and asked her what she thought would be the best way they could help worse-off wineries.

She emailed back ten minutes later: “We can offer floor space. … They can use the press and forklift for sure.”

Burgess, who lost some small bottling equipment, but no wine, told the Napa Valley Vintners that someone could store barrels for free in one of his warehouses. The message spread quickly and he heard from a few people who were interested. But nothing official has been agreed upon yet.

“One guy -- and I can’t name any names,” Burgess said. “But he isn’t sure if his building is gonna be yellow-tagged or red-tagged. So, we’ll see.”

Because they all share some basic knowledge of the wine world, Burgess said it makes sense that the discussions of damage and help remained mainly within industry circles.

“It’s not like Red Cross can help,” he said. “It’s like, ‘Sterilize what? Do what with the barrels?’ ”

Offering to help his competitors seemed natural, Burgess said, especially since they’ve all teamed up in the past to deal with pests and worrisome legislation.

“There’s a lot of camaraderie,” he said. “There’s a lot of people I’d give a key to this place.”

Perdue also created a public clearinghouse where vintners could ask for and offer help.

A computer programmer, he got the idea for the website as he scrolled through Twitter in the first hours after the earthquake and noticed people using #napaearthquake to post messages about unrelated things. It quickly occurred to him that he should buy the Internet domain with that name.

“I grabbed napaearthquake.com before trolls could grab it,” he said proudly.

He later offered the Web address to the trade group and it now redirects to the group’s website, which links back to his clearinghouse, where a wine-law attorney offered free, two-hour coaching sessions, a man who works at a winery in Paso Robles volunteered his skills with a forklift, and a self-described “PR ninja” offered services.

Although no one posted asking for help, Perdue said he knows they’re out there.

“I can tell from traffic going into the site that most people visiting are wineries or wine people,” he said. “But people don’t want that attention.”

But in the presence of their peers, vintners let their guard down. They started to let the stress show a bit.

Napa Barrel Care owner Mike Blom, who was a day into his trip to Maui when the quake hit, flew back immediately and said he’s been juggling texts and calls ever since from vintners who use his humidity-controlled warehouse.

“I get calls every minute asking, ‘How’s my inventory?’” Blom said.

Outside the warehouse on Tuesday, a man shook his head as he walked past a pile of bent strips of broken barrels that looked like a messy, oversized bird’s nest.

“Terrible,” he said. “This is devastating.”

Nearby, Erika O’Brien of X Winery tipped a cracked barrel onto its edge and rolled it away from the warehouse. Perdue asked if the winery lost a lot. She shrugged and said they’d be OK.

“I bet some of these folks won’t be in business next year,” Perdue said.

She agreed and started rolling another barrel.

Back inside, a tall man in Nike tennis shoes stained pink from the cleanup greeted Perdue and pointed at shattered barrels now emptied of aging Cabernet.

“It’s a mess,” he said. “We’re just making it day by day.”

Perdue pointed at the mixture of dirt and wine covering the ground.

“We’ve got the most expensive mud in the state right here,” he said.

Twitter: @marisagerber

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.