In court, ‘Shrimp Boy’ Chow is described as a mobster and a model citizen

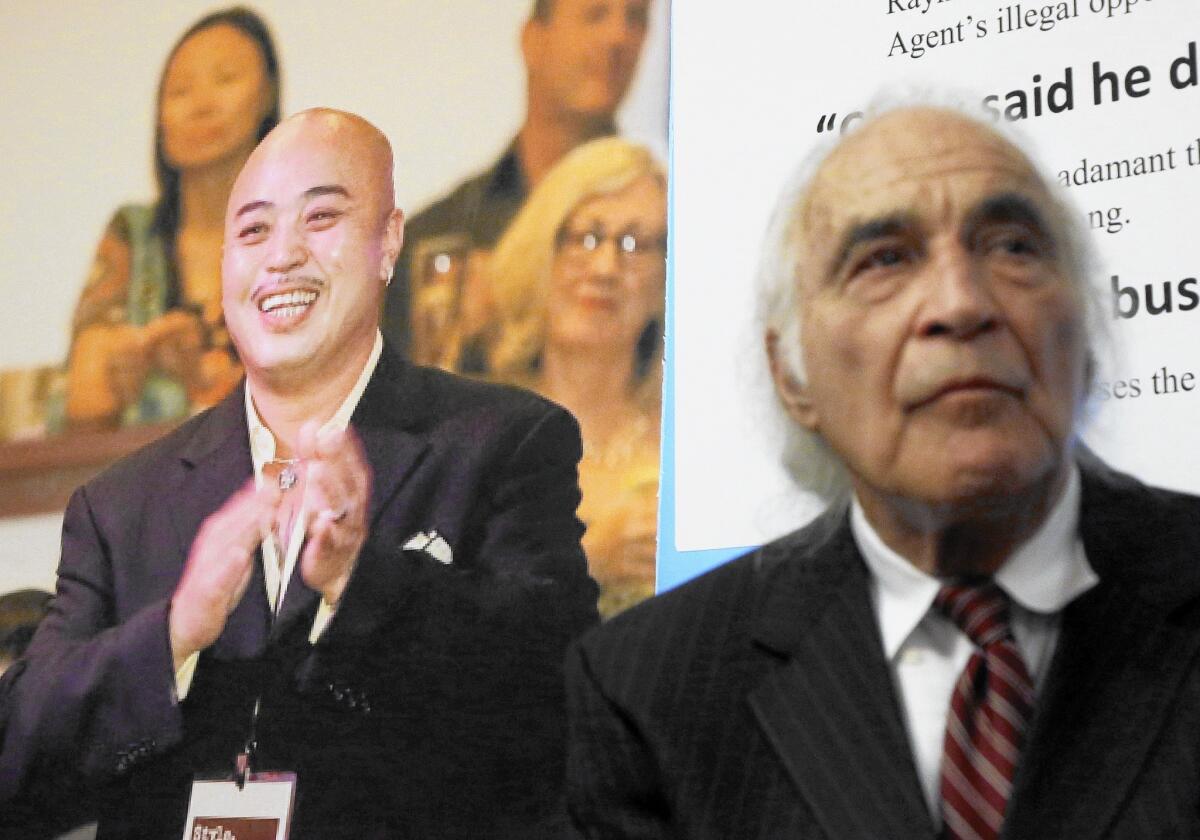

J. Tony Serra, right, is defending Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, left, in his trial.

The trial of Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow in a massive racketeering and murder-for-hire case opened here Monday with wildly divergent visions of the bald man who sat quietly in a gray wool sweater, listening to a Cantonese translation of the proceedings.

The prosecution told jurors that Chow was a clever gang boss who controlled a violent criminal enterprise, a man so cold he laughed when he heard that a rival he is charged with conspiring to kill was dead.

The defense cast him as a reformed criminal turned impoverished community servant who, despite the outrageous conduct of an undercover agent who pushed countless envelopes of cash on him, never committed any crime.

“Like planets revolving around the sun, this case is about the man at the center of [a] criminal underground universe,” Assistant U.S. Atty. S. Waqar Hasib told the panel seated in the courtroom of U.S. District Judge Charles R. Breyer.

“My client,” countered lead defense attorney J. Tony Serra, “did not participate in any criminal act.... He changed his life.”

In the biggest surprise of the day, Serra told jurors that Chow, 55, would be taking the stand in his own defense.

“His testimony will make all the difference,” Serra said after Chow rose, on cue, from the defense table with a beaming smile and a nod and briskly told jurors in accented English, “Good afternoon.”

Like planets revolving around the sun, this case is about the man at the center of that criminal underground universe.

— Assistant U.S. Atty. S. Waqar Hasib

The closely watched trial, expected to last through January, is the first resulting from a lengthy probe that in addition to Chow netted 28 others, including former state Sen. Leland Yee.

Yee pleaded guilty in July to racketeering charges related to accepting bribes in exchange for political favors, money laundering and conspiracy to traffic in arms. Half a dozen of Chow’s other co-defendants pleaded guilty in September.

It was only then that the murder counts were added to the indictment. The most serious alleges that Chow arranged the murder of Alan Leung, who preceded him as dragon head of the Ghee Kung Tong, a Chinatown fraternal organization.

Hasib began his morning opening statement with a detailed account of that slaying, carried out on the edge of Chinatown in 2006 on a rainy day “much like today.” Three men will testify in support of the allegation that Chow was involved in Leung’s killing “in order to gain entrance to a criminal enterprise or enhance his standing in it.”

Two are former co-defendants who had a falling-out with Chow and a third is serving a prison sentence in an unrelated case. That man said he drove two others to Chow’s home a few days before Leung’s killing, and then on the evening of the fatal shooting drove the same men to Leung’s business. He says he later watched them disassemble their guns and toss them in the bay.

Chow is also charged with conspiring to murder Jim Tat Kong, an alleged gang rival. A separate witness is expected to testify that Chow asked him to arrange that killing. When he told Chow he was ready to proceed, he has said, Chow told him it had already been taken care of.

“These people, they are criminals,” Hasib conceded to jurors. “They are very violent. You probably won’t like them. But the question you should be asking ... is, do you believe them? What they’re saying, does it make sense? Does it fit with the [body wire] recordings” that constitute the bulk of the evidence in the case?

Serra, in turn, bellowed: “The evidence will not show that my client murdered or participated in the murder of anyone. Period!”

He showed jurors the scheduled witnesses’ extensive rap sheets and called the addition of murder counts just two months ago an “act of desperation by prosecutors.”

The witnesses “jumped on the bandwagon right at the end” in exchange for leniency, and “they themselves will admit that … they have given in some instances inconsistent statements. You will not believe them.”

The rest of the case largely revolves around UCE 4599, an undercover FBI agent who went by the cover name David Jordan. It was Chow, Hasib told jurors, who introduced Jordan to more than a dozen people who then worked with him to launder hundreds of thousands of dollars and traffic in contraband cigarettes and stolen liquor.

It was Chow, Hasib said, who was running the show behind the scenes. And though Chow often resisted taking money from Jordan, Hasib said, “every time David Jordan offered him an envelope [of cash], he put it in his pocket.”

His protestations that he was reformed, Hasib said, were an act.

“What you will hear on these undercover recordings of Raymond Chow is a man who has almost as elaborate a cover as David Jordan himself,” Hasib said. “He’s a man who wants to stay fastidiously clean — ‘No, no, no, I don’t want to know about that.’ But unlike David Jordan, you will hear that cover drop.

“You will be left with one inescapable conclusion,” he said, “that Raymond Chow is guilty.”

Serra told jurors that he will draw on the very same recordings, and he urged them to listen carefully because each side interprets the evidence differently.

Chow, he read to them, told Jordan, “I don’t run the streets no more,” “I quit while I was best,” “I just stay out of it,” “I don’t live that lifestyle anymore.”

“That’s not a cover story. He’s telling it like it is,” Serra said. Chow had “an epiphany, a change of life. Before you sits a good person, not a bad person.”

Serra also invited jurors to take offense at the methods of what he called the outlandish government investigation. The more than $1 million spent on fine hotels, restaurants and attire. The $2.4 million supplied for the money laundering, contraband cigarettes and stolen liquor.

“I’m not saying my client was entrapped because they waved a bunch of money in front of him,” Serra added, ultimately saying that “large quantities of reasonable doubt” will compel jurors to acquit.

“They waved a bunch of money in front of him, but he never went for it.”

Twitter @leeromney

ALSO

Navy launches second test missile off Southern California coast

Ride-sharing services hurting Bob Hope Airport parking revenues, officials say

Chilly storm could bring showers to L.A.; Northern California hit by snow and lightning

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.