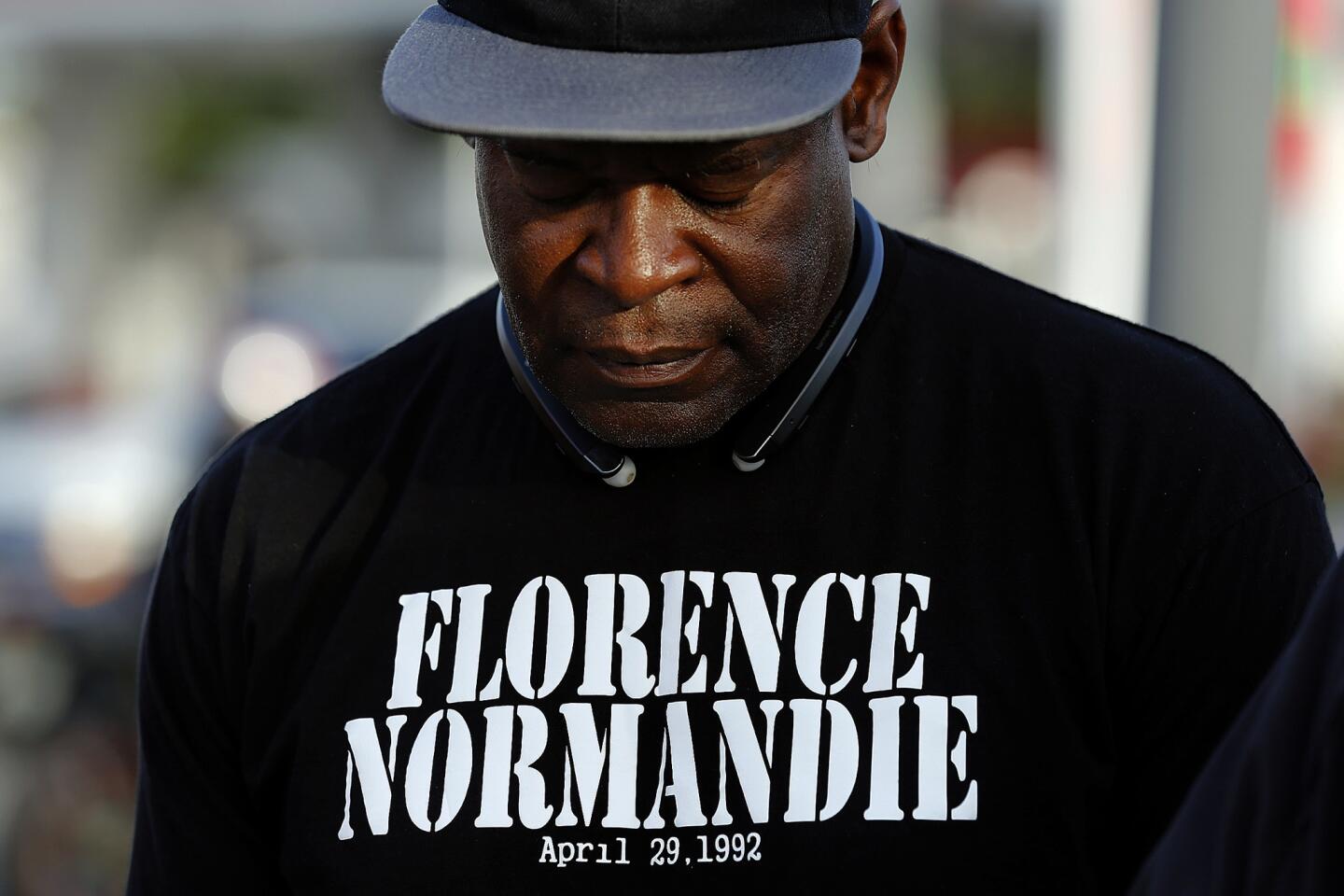

At the corner of Florence and Normandie, marking causes of L.A. riots: ‘It’s important to remember what started it’

When an angry mob erupted in violence across Los Angeles 25 years ago this week, two names were commonly invoked by those in the streets.

One is well-known: Rodney G. King, the black man beaten by a group of baton-wielding police officers whose acquittal in a Simi Valley courtroom sparked the riots on April 29, 1992.

King survived his 1991 beating. Latasha Harlins, the other person invoked by looters, did not survive her injuries.

Harlins, a 15-year-old black girl, was shot in the head by a South Korean-born shopkeeper. A jury convicted the shopkeeper of manslaughter, but a judge imposed a light sentence without prison time, fueling rage and racial tension in the city.

On Monday, as the anniversary of the 1992 riots approaches, residents and community activists gathered at Florence and Normandie avenues, the notorious South L.A. intersection that was ground zero of the unrest, to commemorate King, Harlins and the 54 people who died in the riots.

The event is among the first in a week recalling the riots, which left about 2,000 people injured and $1 billion in property damage across the city.

“It’s important to remember what started it,” said Latasha’s aunt, Denise Harlins, one of a dozen at the candlelight vigil. In the quarter-century since buildings burned and throngs took to the streets, she said people had forgotten the complex forces that drove the city to explode.

“Rodney King and Latasha Harlins and many social ills that was going on at the time brought April 29, 1992, about,” Denise Harlins said.

Najee Ali, who organized the small vigil, said the prayerful gathering was meant to show unity.

“We are here for all the victims,” Ali said. “We are here today to say you are not forgotten.”

But the memory of the riots remains a point of division. Some recall when columns of smoke filled the sky during days of insurgent anarchy and a breakdown of order.

Others eschew the term “riot” and call it an uprising or rebellion, emphasizing the deep sense of injustice that powered a raging and destructive mob.

For many, Rodney King embodied that sense of injustice, particularly at the hands of law enforcement.

On the night of March 3, 1991, King had been drinking when officers pulled him over on a dark stretch of Foothill Boulevard in Lake View Terrace. He was acting erratically when he stepped out of the car.

A group of L.A. Police Department officers surrounded him, shot him with Tasers and struck him more than 50 times with solid aluminum batons.

A neighbor, awakened by the helicopters, rushed to capture the scene with his camera. Once the grainy video hit the airwaves, the beating thrust King into the spotlight.

Four officers — all white — stood trial for the beating. After seven days of deliberations in a Ventura County courthouse, a jury with no black jurors acquitted them all. Shortly afterward, the anger over the verdict spilled into the streets, as throngs set fire to entire blocks and stormed police buildings.

A group of young black men walked into a Korean-owned liquor store three blocks west of Florence and Normandie and snatched several bottles of liquor.

They hit the store owner’s son and broke the storefront window. One yelled, “This is for Rodney King!”

“We are always going to have a Florence and Normandie popping up every now and again.”

— Timothy Goldman, who recorded the early hours of the L.A. riots

At Florence and Normandie, a white truck driver, Reginald Denny, was grabbed out of his vehicle and bashed by four black assailants with a brick and other objects. His beating was documented by helicopter news crews overhead — footage that would later help secure convictions in the case.

Denny survived his beating and like King and Harlins, became another symbol of the massive upheaval in L.A.

Timothy Goldman, who recorded the early hours of mayhem at Florence and Normandie and was credited with shielding some people from harm, joined Monday night’s vigil.

But Goldman’s focus was as much on the events of 25 years ago as recent history, when crowds were galvanized by the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and the death of Trayvon Martin, a South Florida teen.

“We are always going to have a Florence and Normandie popping up every now and again,” said Goldman, sounding resigned to the view that police use excessive force more commonly in encounters with black people. “We can go to Ferguson, Baltimore and Charlotte and Baton Rouge. It will continue.”

Latasha Harlins’ death still disturbs many across L.A.

Latasha walked into a convenience store on 91st and Figueroa streets on March 16, 1991, put a bottle of orange juice in her knapsack and walked toward the counter. The owner, Soon Ja Du, claimed the girl was trying to steal the juice.

Witnesses said Latasha told Du she intended to pay and revealed two dollar bills in her hand; police later concluded that there was “no attempt at shoplifting” by Latasha.

But Du grabbed the teen’s sweater and as the two struggled, Latasha struck Du in the face and broke free. Latasha tossed the juice on the counter and walked toward the door. Du picked up a handgun and fired a shot into the back of Latasha’s head, killing her.

The deadly confrontation was captured by fuzzy security footage.

A jury found Du guilty of voluntary manslaughter, with a maximum sentence of 16 years in prison. The judge gave her probation, 400 hours of community service and a $500 fine.

Feeling wronged by the judge’s lenient sentence, Latasha’s family helped launch a campaign that called on the judge to step down, and lobbied for the district attorney to appeal the sentence.

A state appeals court upheld the sentence in April 1992, just a week before the four officers were acquitted in the beating of King.

Reflecting on the 25th anniversary of the riots, Denise Harlins sees little progress.

“When you look at the news and social media and police brutality, it hasn’t gotten better,” she said.

As the vigil closed on the corner of Florence and Normandie, Ali lit the wicks of candles and placed them on the curb. His hope: for the message of reconciliation and healing to resonate.

Twitter: @AngelJennings

Twitter: @MattHjourno

ALSO

Marchers gather to commemorate 102nd anniversary of Armenian genocide

Water under Oroville spillway probably caused February collapse, state consultants say

Man sentenced to 15 years for starting massive Da Vinci blaze in downtown L.A.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.