Remembering service members killed in Vietnam — one name at a time, for three days

One by one the names were read out loud, a solemn tolling of the fallen.

All weekend long, volunteers took turns standing at a lectern outside the Veterans Museum and Memorial Center to read the names of San Diegans killed in the Vietnam War or listed as missing in action.

There are more than 450 names on the list, and it took about an hour to read through them all, each name followed by the ringing of a bell. When the readers were finished, they read the names again.

And again.

They read for about eight hours on Saturday, and another 10 hours Sunday. They read when passers-by stopped to listen, and they read when no one else was there. It wasn’t about the audience.

Today, at the beginning of a Memorial Day ceremony at the museum, they’ll read the names one more time.

“We do it to honor those who gave the ultimate sacrifice for their country,” said Tom Slaughter, a board member for the local chapter of the Vietnam Veterans of America.

This isn’t like the well-attended events at Fort Rosecrans and Miramar, the national cemeteries in San Diego that will be decorated today with thousands of American flags and red roses. It isn’t military planes flying over Mt. Soledad. There are no speeches by admirals or brigadier generals.

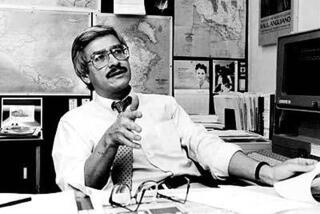

But there is Benjamin Rodriguez, reading names.

Albert Banuelos Jr. Thomas Peavy. Gilbert Maestas. Jesus Ortega Jr.

Those were among the people Rodriguez honored on Saturday, and he felt a personal connection. They all went to Lincoln High in San Diego, and they all went to Vietnam.

Rodriguez came home. The others did not.

“I say their names and I think of them as high school friends, and I salute them,” he said.

And he tries not to cry.

Vietnam War veterans took turns on Saturday, speaking the names of the fallen during a Memorial Day weekend observance at the Veterans Museum and Memorial Center in Balboa Park.

The readings have been going on for more than 30 years.

In 1969, a handful of volunteers worked with the local Roman Catholic Diocese to build what was called the San Diego Peace Memorial on church property in Old Town.

Funded through private donations, it was erected in response to the protests against the Vietnam War that were erupting across the country. It featured two concrete monuments topped with plaques containing the names of San Diego County’s casualties.

The list grew as the war continued — it was still more than five years from ending — and two more plaque-topped monuments were added in 1974.

Like the war itself, the memorial was controversial. Some saw it as a glorification of combat. American flags were burned at the site, rotten eggs thrown at the markers.

After the war ended, the memorial took on a sacred air, and veterans saw it as a place of reconciliation. There was pride in the fact that it was one of the first Vietnam memorials in the nation, pre-dating the reflective granite wall in Washington by more than a decade.

Sometime in the mid-1980s, volunteers started gathering at the San Diego monuments there on Memorial Day weekends and reading the names aloud for 48 straight hours.

It made for a sometimes-odd juxtaposition at the corner of San Diego Avenue and Twiggs Street, somber reflection bumping up against camera-toting tourists wandering by during the day and boozy revelers carrying on from nearby bars at night.

In 1994, the diocese sold the property. The memorial was moved to its present spot, outside the Veterans Museum in Balboa Park.

Some people worried that moving the memorial would rob it of its emotional power, and that with fewer visitors walking by it every day, those honored on its plaques might soon be forgotten.

But the volunteers working this weekend in two hour blocks, four readers per hour, show that hasn’t happened.

After each name is read, a bell is rung — once for those killed in action, twice for those missing.

The readers never know how many people might be listening, or who they might be. Sometimes, Rodriguez said, they are survivors of the San Diego County residents killed in the war.

Sometimes they are from elsewhere, and ask to speak the names of their loved ones, too.

The requests are always honored.

Wilkens writes for the San Dieogo Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.