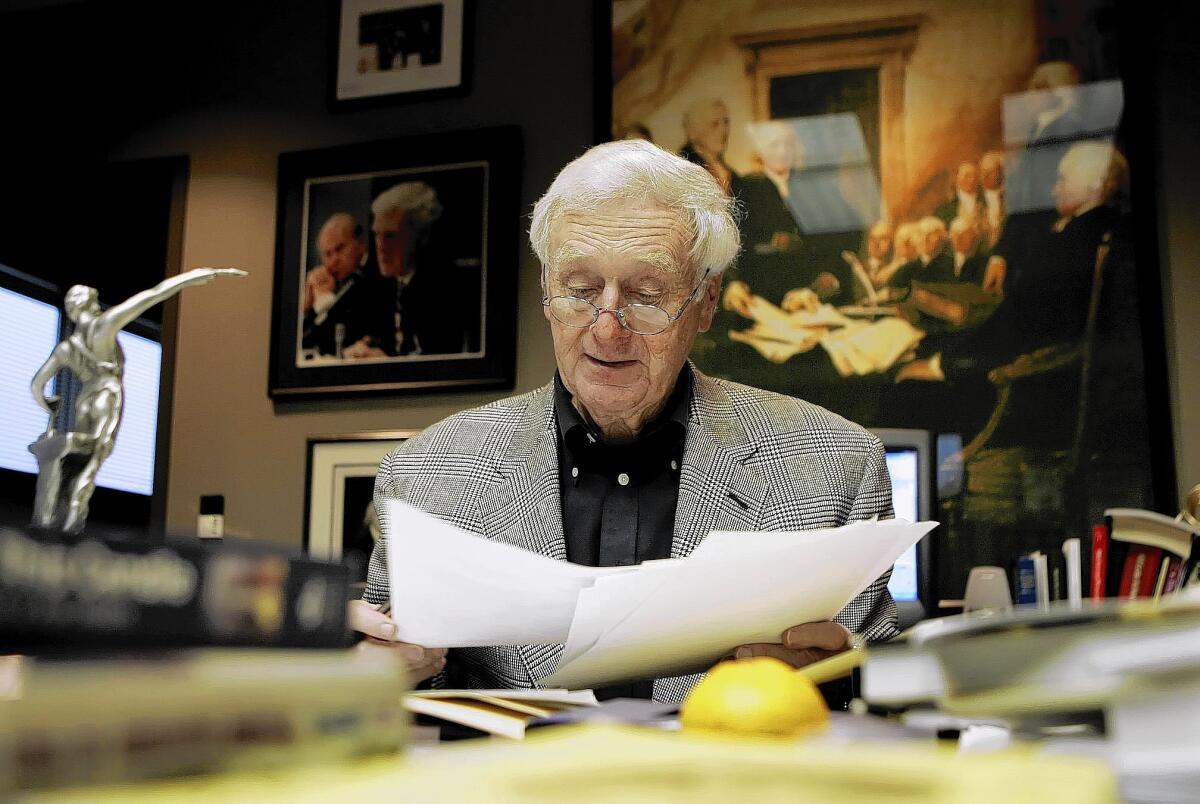

John Seigenthaler, journalist and civil rights activist, dies at 86

John Seigenthaler, a journalist, civil rights activist and “right hand” to Robert F. Kennedy — who once hired a young reporter named Al Gore to work under him at the Tennessean — died of colon cancer Friday in Nashville. He was 86.

His death was confirmed by his son, John M. Seigenthaler, an anchor with Al Jazeera America.

As Kennedy’s go-between to the Southern states in the early 1960s, and as a maverick journalist, Seigenthaler infuriated segregationists at a time when few white professionals were willing to risk their wrath, said the Rev. James Lawson, a civil rights advocate and teacher now living in Los Angeles.

Lawson was the young architect of the Nashville sit-in campaign when Seigenthaler was a newspaper editor. He recalled the distinct approach that Seigenthaler and the Tennessean staff took toward the movement. The Tennessean “did not operate from the bias of segregation and racism but simply reported what was going on,” Lawson said.

Seigenthaler was administrative assistant to Robert Kennedy at the Justice Department from 1960 to 1962, worked on his presidential campaign and remained close to the Kennedy family.

With his Southern accent, he was a natural choice when Kennedy, then attorney general, needed a liaison to the South in the era of Freedom Rides, said Nashville lawyer and activist George Barrett, who was Seigenthaler’s lifelong friend.

But Seigenthaler’s political career was short. He returned to journalism after his stint with the Justice Department, and mostly remained a journalist until 1991, when he began to devote himself to his other passions: civil rights, the 1st Amendment and literature.

“John never played it safe,” said Ken Paulson, president of the First Amendment Center in Nashville, which Seigenthaler founded. “He was one of those rare individuals whose good reputation did not do him justice.”

John Lawrence Seigenthaler Jr. was born in Nashville on July 27, 1927, the son of a sheet-metal worker and the oldest of eight. His father died young, and Seigenthaler helped his Irish Catholic mother raise the younger siblings.

The mere fact of being Catholic — a distinct minority in Nashville — probably contributed to Seigenthaler’s lifelong identification with outsiders and underdogs, Barrett said.

Seigenthaler’s mother loved literature and raised her son on Shakespeare; he became a reciter of poetry and a lover of books.

Although he attended Peabody College for only a couple of years and never earned a degree, his love of the written word proved defining. “He was in many ways self-taught,” his son said.

Seigenthaler served three years in the Air Force and started at the Tennessean as a copy boy. According to the newspaper, he met his wife, Delores, while covering a community concert in which she was singing. He distinguished himself with an expose of an insurance fraudster. While on assignment another time, he grabbed a would-be suicide to keep him from jumping.

But it was his work on corruption in labor movements that drew Kennedy’s attention. After completing a Nieman fellowship in 1959, he went to work for Kennedy and later for his campaign.

Though part of Kennedy’s inner circle, he was not with him when he was assassinated in 1968.

It was while acting as Kennedy’s liaison in Montgomery, Ala., that Seigenthaler and a Justice Department attorney intercepted Freedom Riders in the midst of a mob attack. Trying to help two young women, Seigenthaler was hit on the head and blacked out.

Barrett, who visited him in the hospital, recalled Seigenthaler sitting up in bed and triumphantly hoisting a bottle of Jack Daniels sent by the publisher of the Tennessean. “John had a lot of courage — I mean, he really did,” Barrett said.

That courage would cost him: His son recalled many years of death threats against his family and coming home from school to find police guarding his house.

Seigenthaler never lost his muckraking instincts. Long after the Kennedy years, he made waves in Nashville as the Tennessean’s editor and publisher, sending a reporter to infiltrate the Ku Klux Klan and fighting for open public records. Yet he always had a published home phone number for the inevitable angry calls, his son said.

He later became an editorial director for USA Today. After retirement, he founded the First Amendment Center and hosted a public television show, “A Word on Words,” about books.

He fought for civil rights to his last days, said Paulson, who called Seigenthaler “a great Southern gentleman who would speak slowly and think quickly.”

If anything, Seigenthaler increased his work pace after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. He urged Americans to not let fear short-circuit freedom. “He could have rested on his laurels and have people give banquets for him,” Paulson said. “Instead, he kept pushing forward.”

In addition to his wife and son, Seigenthaler is survived by a grandson, three sisters and a brother.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.