Albert Reynolds dies at 81; former Irish prime minister

Albert Reynolds, the risk-taking Irish prime minister who played a key role in delivering peace to Northern Ireland but struggled to keep his own governments intact, died Thursday at his home in Dublin after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. He was 81.

His eldest son, Philip, confirmed his death.

Reynolds, a savvy businessman from rural County Roscommon who made millions running dance halls and a pet food company, led two feud-prone coalition governments from 1992 to 1994.

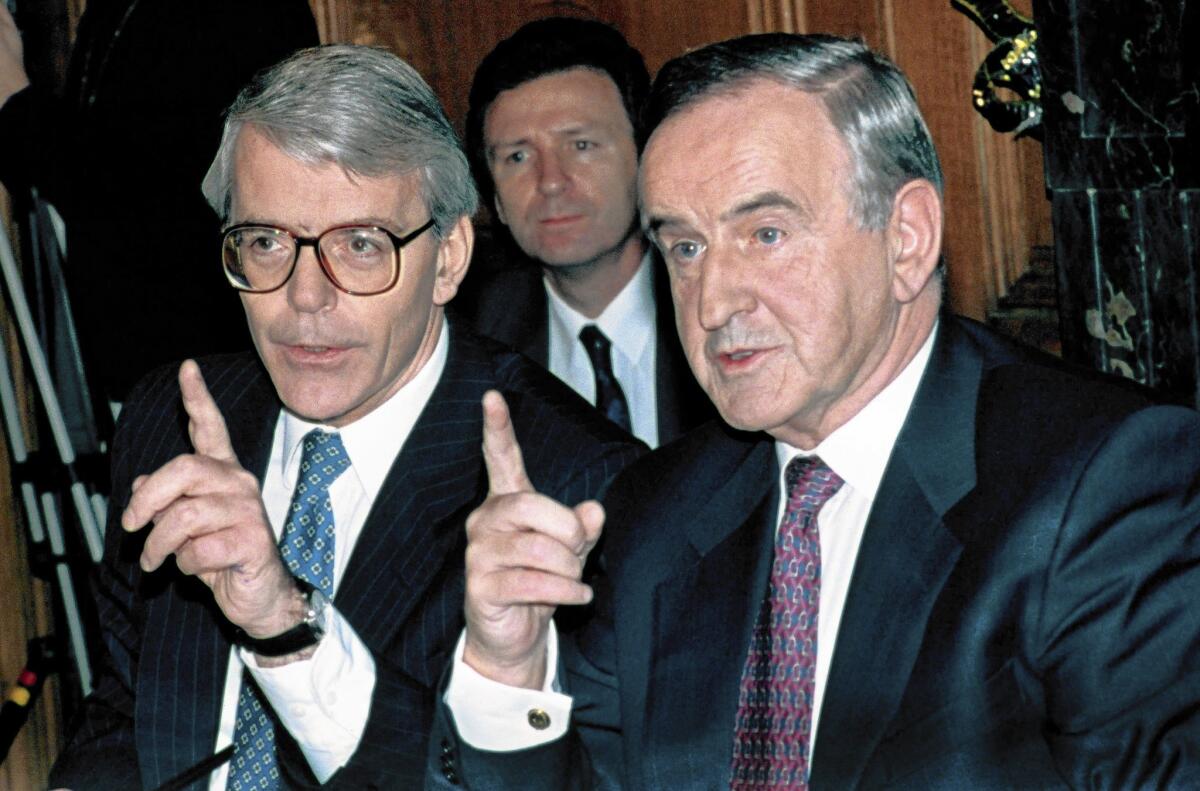

During his turbulent tenure, Reynolds made peace in neighboring Northern Ireland his top priority. With British Prime Minister John Major at his side, he unveiled the Downing Street Declaration, a 1993 blueprint for peace in the predominantly British Protestant territory. To drive it forward, he successfully pressed the outlawed Irish Republican Army to call a 1994 cease-fire.

“Everyone told me: You can’t talk to the IRA. I figured it was well past time to bend some rules for the cause of peace,” Reynolds said in 1994, when he was being touted as a Nobel Peace Prize candidate.

Yet within months of that peacemaking triumph, a stunned Reynolds was forced to quit as leader of Ireland’s centrist Fianna Fail party after his coalition partners in the left-wing Labor Party withdrew from the government in protest over his dismissive management style.

Reynolds’ appetite for walking a political tightrope worked wonders in Northern Ireland, where a quarter-century of conflict had left more than 3,500 dead. He built alliances with U.S. President Bill Clinton and Irish-American leaders, who wanted to coax the IRA-linked Sinn Fein party in from the political cold. Pushing from one direction, Reynolds demanded that Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams deliver an open-ended IRA truce; from the other, he cajoled a skeptical, reluctant Major toward direct contact with Sinn Fein.

“We’ve been able to have the fiercest of rows without leaving scars. I understood Albert’s difficulties and he understood mine,” recalled Major, who described his Irish counterpart as “a lovable man.”

Clinton said Reynolds’ work alongside Major provided the bedrock for Northern Ireland’s eventual 1998 peace accord “and our world owes him a profound debt of gratitude.”

Many analysts have argued that Northern Ireland peacemaking would have progressed more quickly had Reynolds stayed in power. But his daredevil streak proved unworkable in a parliament where his long-dominant Fianna Fail — Gaelic for “Soldiers of Destiny” — no longer commanded a majority on its own.

Even before becoming prime minister, Reynolds was accused of recklessness. In the late 1980s, while running Ireland’s commerce department, he concocted a state insurance scheme for the country’s top beef baron to export cattle to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Taxpayers ultimately paid the exporter about $300 million in losses when Iraq defaulted.

Reynolds’ first coalition government collapsed in 1992 during a state investigation into the ethics of that deal and wider corrupt practices in Ireland’s beef exports. His government partner, the Progressive Democrats, demanded the probe and soon withdrew as Reynolds denied wrongdoing.

His second government fell apart almost as quickly as he repeatedly took decisions without consulting his new junior partner, Labor. The final straw came when he dismissed Labor’s objections to the promotion of his attorney general, a Catholic conservative accused of suppressing a Northern Ireland extradition warrant for a pedophile priest.

Born Nov. 3, 1932, in Rooskey, County Roscommon, Reynolds is survived by his wife of 52 years, Kathleen, and seven children.

Pogatchnik writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.