Joyce Miller dies at 84; voice for women in labor’s top ranks

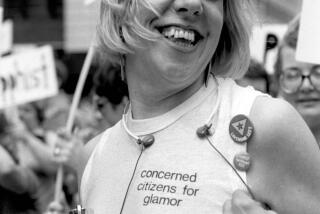

Joyce D. Miller, who rose from an assembly line job to the top ranks of American labor as the first woman on the AFL-CIO executive council, died June 30 in Washington. She was 84.

The cause was a stroke, said her daughter, Rebecca Miller.

Miller was an advocate for women in the workplace for more than three decades. A divorced mother of three, she worked her way up to leadership positions in the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America during the 1960s and ‘70s. As the women’s movement gathered strength, she helped found the Coalition of Labor Union Women in 1974 and became its president in 1977.

She was vice president of the clothing workers union in 1980 when she was elected to the 35-member executive board of the AFL-CIO, which sets policy for the labor federation.

She got there, she said, not by being strident or militant but by hard work and being “acceptable.”

“If you’re not acceptable, you can’t promote your ideas because you’ll just be dismissed,” she told the Associated Press in 1980. “Unless we’re part of the mainstream of labor, we’ll just be out on the street shouting.”

The AFL-CIO executive council broke with longstanding tradition to open its ranks to Miller. Under the federation’s longtime chief, George Meany, council membership was limited to presidents of its affiliated unions, all of which were headed by men, and no union could have more than one representative. The head of her union, Amalgamated Clothing Workers, already belonged to the council.

Miller was elected under Meany’s successor, Lane Kirkland. Her selection signaled that the AFL-CIO finally was recognizing that women, who were entering the workplace at a faster pace than men, were important to the labor movement.

During the 13 years Miller served on the AFL-CIO board, she advocated issues such as equal opportunity, equal pay, child care, parental leave and the rights of pregnant women in the workplace.

“She was a bulwark,” said Muriel Tuteur, a veteran labor activist who helped Miller launch the nation’s first union-sponsored day care center in Chicago in 1969. “She was a very strong personality and a very strong feminist. To help improve the quality of life for people, that’s what Joyce was all about.”

She was born Hannah Joyce Dannen in Chicago on June 19, 1928. Her father ran a dry goods store and her mother was a teacher at a school for the deaf, mute and blind.

Miller studied at the University of Chicago, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1949 and a master’s in education in 1951. While a student she worked on the assembly line in a gum ball factory and joined the bakery and confectionery workers union.

She was working as an organizer for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers when she married a fellow organizer, Jay Miller, in 1952. For the next decade she raised their three children and worked part-time as a teacher and union volunteer. Her marriage ended in divorce in 1964.

As education director of the clothing workers union, she helped organize a child-care program that the federal government later praised as the “the Rolls Royce of day care.” The project arose out of her personal experiences looking for quality child care when she returned to work.

“You just never know for sure whether someone was going to work out or not, and there was all that guilt,” she told The Times in 1980. “I remember one day going to work and leaving a new woman with my children. I came back at 6 p.m. and this woman was drunk.”

In 1972 the international union moved her to New York to start a nationwide social services program for its members. In 1974 she helped found the Coalition of Labor Union Women to strengthen the role of women in unions and of union women in the feminist movement.

She was vice president of the AFL-CIO and the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union in 1993 when she was named executive director of the federal Glass Ceiling Commission under Robert Reich, President Clinton’s Labor secretary. She found that “not only was the ceiling still in place but it was often made of concrete rather than glass,” said Reich, who called Miller “one of the nation’s clearest and most powerful voices for the rights of working women.”

The commission gathered testimony from around the country on the challenges facing women and minorities who aspire to the executive suite. But Miller said she wanted to focus attention on barriers to mobility at every stage in the pipeline, including helping those at the bottom “with their feet stuck in the mud.”

In addition to her daughter Rebecca, Miller is survived by sons Joshua of Easton, Pa., and Adam of Marina del Rey; a brother; and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.