June Wayne dies at 93; led revival of fine-art print making

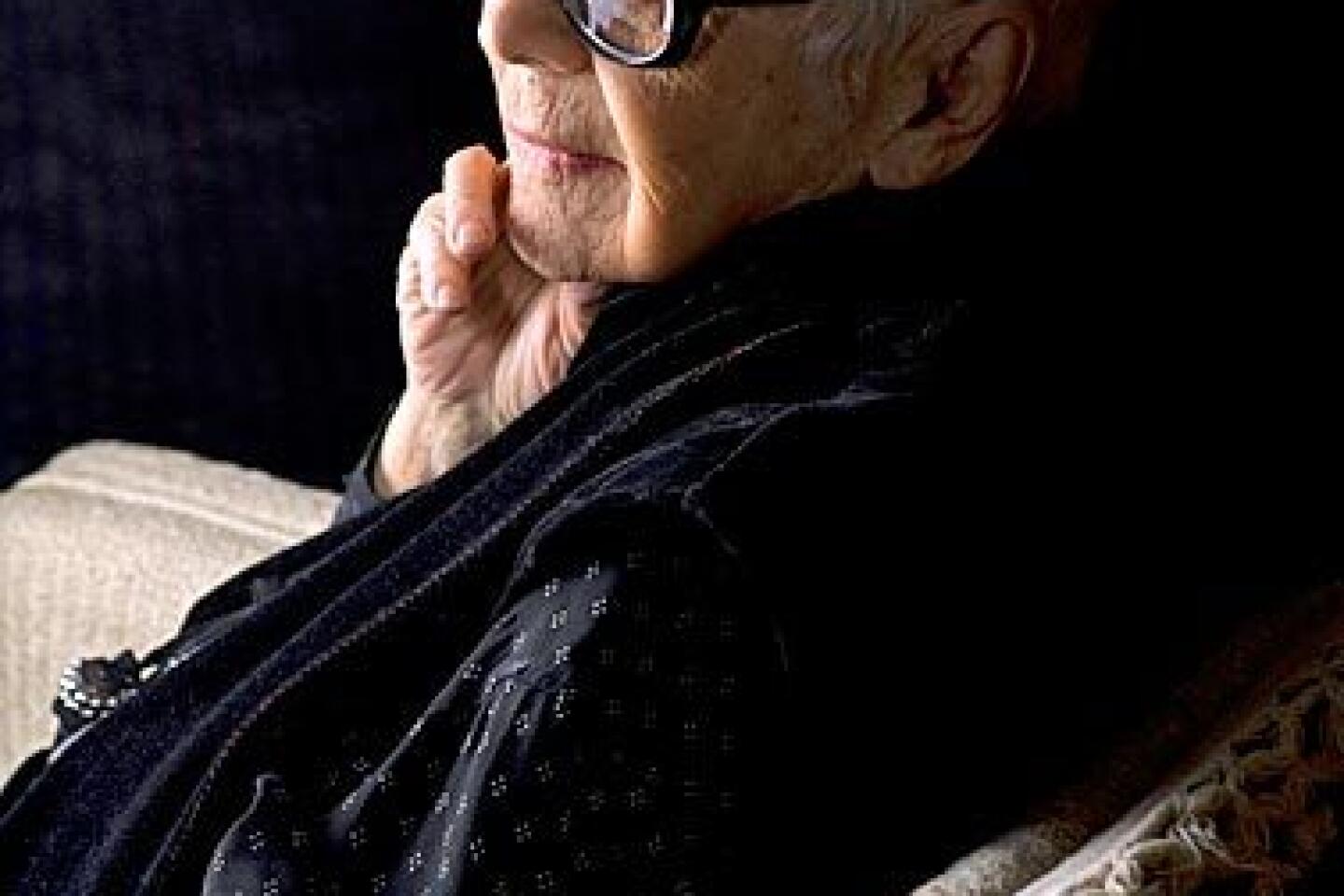

June Wayne, who helped pioneer a revival of fine-art print making in the 1960s when she founded the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, has died. She was 93.

An accomplished artist in her own right, Wayne died Tuesday at her home in Los Angeles after a long illness, according to her assistant, Larry Workman.

Wayne gained an international reputation starting in 1960 when she began to invite leading artists to collaborate with professional printers at Tamarind and create artist’s prints.

Painters including Richard Diebenkorn, Sam Francis and Rufino Tamayo, and sculptor Louise Nevelson were among the first artists to work with the printers at Tamarind.

“When June got started, the attitude was ‘real artists don’t make prints,’ ” Marjorie Devon, director of the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque that continues the work Wayne began, said in a 2006 interview with The Times. “It’s a testimony to her persuasiveness that she got top artists interested.”

Wayne recalled those early years in a 1990 essay. “In my mind, lithography has been linked to the great white whooping crane which, like lithography, was on the verge of extinction when the Tamarind Workshop came into being,” she wrote.

“The artist-lithographers, like the cranes, needed a protected environment and a concerned public so that, once rescued from extinction they could make a go of it on their own.”

More than bringing artists and artisan-printers together, Wayne published a steady supply of information about the technical processes being developed at the workshop.

The basic method for making a lithograph is to draw a design on a stone or metal surface, using a greasy substance. When water and ink are applied, the greasy parts absorb the ink and repel the water. Nuances and variations in the basic technique make the difference. Traditionally, master printers were like famous chefs who refused to share their recipes. “June wanted nothing kept secret,” Devon said.

While her reputation was based on her creative work at Tamarind, Wayne was also a prolific painter and lithographer who used science, social issues and personal history as themes. Self-taught, and a self-made success, she began early in her career to lobby for government sponsorship of the arts and artistic freedom from government censorship.

“Wayne’s uniqueness lies precisely in her departures,” then-Times art critic William Wilson wrote in 1998. “She offers a fruitful alternative model for the artist. Never allowing a signature style to imprison her, like a creative scientist she investigates her ideals and passions even when they lead her out of the studio. She does more than make superior art in Los Angeles. She helped mold its larger culture.”

But she never reached the prominence some said she deserved. Experts offered several reasons for her limited recognition.

“She has not fallen into any of the art movements that have had such publicity,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator Victor Carlson said when a retrospective of Wayne’s work opened in L.A. in 1998. He mentioned Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting. “None of those brackets explain her,” he said. “I think that a lot of critics have not known what to make of her.”

Carlson also said Wayne, by devoting more than 10 years to Tamarind, slowed her progress as an artist. In her maturity, she “had not achieved her full potential,” he said.

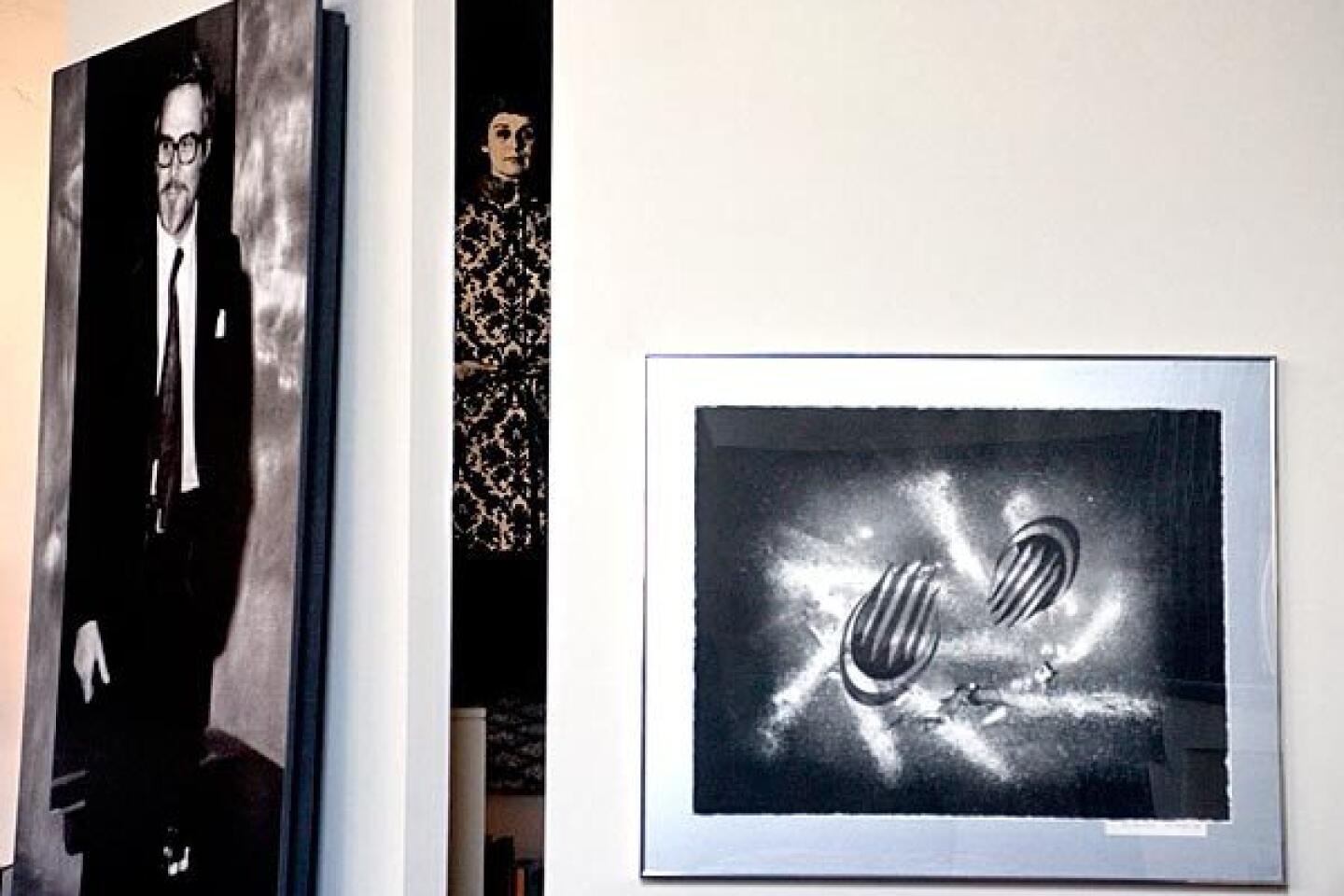

Wayne’s unusual taste in subject matter led to paintings, lithographs and tapestries about DNA structure, atomic fission and organic chemistry. Her 1965 lithograph “At Last a Thousand” was inspired by lemmings known for their attempts at mass migration by way of crossing Arctic waters. In the process thousands of lemmings drown.

The lithograph shows small creatures in chaos, many of them falling off ledges into an abyss. The aerial perspective of the work recalls a satellite image of a disaster area. The work is “the landscape of a cataclysmic galaxy,” art historian Arlene Raven wrote in a catalog essay for the Wayne retrospective.

Many of Wayne’s ideas for art came out of her daily life in Los Angeles. An early painting, “The Tunnel” (1949), was inspired by her drives through the 2nd Street tunnel downtown. The painting suggests movement through time and space and Wayne’s interest in optics.

Another work, “Northridge” (1994), was inspired by the earthquake centered there. Luminous pigment in the painting appears to crack and expose a black void.

Some of Wayne’s most admired pieces come from “The Dorothy Series,” a tribute to her mother, Dorothy Kline. In 20 lithographs from the 1970s, Wayne used photos and artifacts for an artistic biography.

Her mother was born in Russia and immigrated to the United States as a child. She married but divorced her husband barely one year later. To support herself and her daughter, she sold corsets to Midwest department stores. Wayne used photos, a report card, and marriage and divorce documents in the series.

Wayne’s independent streak, so apparent in her art, made her a role model for several generations of female artists. While the feminist movement of the 1970s expanded, she launched workshops to teach women how to navigate the power structures of the art world, then dominated by men. But she never saw herself as part of any group.

“Some of my problems over the years stemmed from an inability to think of myself as any kind of minority, woman, Jew, artist, whatever,” she later wrote.

Born June Claire in Chicago on March 7, 1918, she dropped out of high school at 15, held various jobs and made paintings of Depression-era scenes. She had her first exhibit in 1935 at a Chicago art gallery when she was 17.

She joined the Works Progress Administration before moving to New York, where she worked for a costume jewelry company. She finally relocated to Los Angeles and worked in production illustration, translating blueprints to drawings for the aircraft industry.

She married a military doctor, George Wayne, and the couple had a daughter before they divorced. She then married Arthur Henry “Hank” Plone, who died in 2003. She is survived by her daughter, Robin Claire Park; granddaughter Ariane Junah Claire; grandson Jevon Claire; and stepdaughter Abby Moore.

Wayne first became interested in print making in the late 1940s. Frustrated by the rudimentary level of training she found in Los Angeles, she went to Paris in 1957 and sought out Marcel Durassier, a printer of artists’ lithographs. They began a collaboration and in 1958 completed “John Donne, Songs and Sonnets,” a series of lithographs based on the poet’s work.

The series was acquired by the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, which later added 248 more lithographs by Wayne. Other large collections of her art are owned by LACMA and Rutgers University in New Jersey. Her work with Durassier gave rise to her vision of Tamarind, she later wrote.

The name for her workshop came to her after Wayne settled on Tamarind Street in Hollywood in 1957. She first used it when she applied for a Ford Foundation grant, outlining her plan to create a place where professionally trained artisan-printers would team with well-known artists to revive the art of lithography.

Wayne opened her studio in 1960 with the help of the first of several grants from the foundation. Through the decade Tamarind continued as a nonprofit center. For Wayne, that status translated to artistic freedom. One of the print makers she helped train at Tamarind, Kenneth Tyler, later founded the Los Angeles print-making studio Gemini G.E.L. Another, Bud Shark, went on to found Shark’s Inc. in Boulder, Colo.

Wayne turned the Tamarind archives over to the University of New Mexico in 1970. At that time the name was changed to the Tamarind Institute, but education and print making continued.

Once she stepped down from her position as director, Wayne, a social activist from her 20s, spent more of her time making art and supporting causes that affect artists.

“I think I run on indignation,” Wayne said in an interview with The Times in 2008, when she was 90.

A celebration of her life is planned.

Rourke is a former Los Angeles Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.