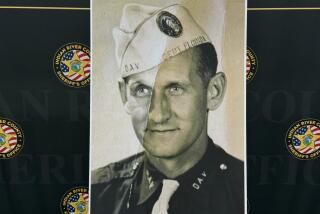

Paul J. Wiedorfer dies at 90; World War II soldier earned Medal of Honor

On Christmas Day 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge, Paul J. Wiedorfer charged 150 yards across a snow- and ice-covered field under intense enemy fire, single-handedly knocked out two German machine gun nests and took 24 prisoners. His spectacular feat earned him the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military honor.

“Suddenly something popped into my mind. Something had to be done, and someone had to do it. And I just did it. I can’t tell you why,” Wiedorfer told the Baltimore Sun in 2008.

Wiedorfer died Wednesday of heart failure at a retirement home in Baltimore. He was 90.

He learned of the honor in May 1945 while recuperating at the 137th U.S. Army General Hospital in England from severe wounds he suffered in a mortar attack while crossing the Saar River earlier that year.

In the attack, a fellow infantryman near Wiedorfer was killed instantly by an exploding mortar shell. Shrapnel ripped into Wiedorfer’s stomach, broke his left leg and riddled his right. Two fingers on his right hand were seriously injured.

“That was Feb. 10, 1945. The sergeant’s back was blown wide open, and he was dead when he hit the ground. I was just lucky, I guess,” he said in the 2008 interview. “I spent more than three years in hospitals recovering from those wounds.”

Another patient was reading Stars and Stripes when an item caught his eye, and he asked Wiedorfer, “How do you spell your name?”

“I said, ‘W-i-e-d-o-r-f-e-r,’ and he said, ‘You just got a medal.’ I said was it the Bronze Star, and he said no, ‘Congressional Medal of Honor,’” he recalled in the 2008 interview.

“To be perfectly honest with you, I wasn’t really sure what the hell it was, because all I was some dogface guy in the infantry,” he told the newspaper.

“All the officers and nurses were wearing their Class A uniforms and there was a band. Gen. E.F. Koening came into the ward and presented the medal,” he recalled. “I really was embarrassed by all the fuss.”

Wiedorfer, the son of a German immigrant who worked for National Brewing Co. and a homemaker, was born Jan. 17, 1921, in Baltimore. He was an apprentice power station operator for Baltimore Gas & Electric Co. when he enlisted in the Army in 1943.

Assigned to Company G, 318th Infantry, 80th Division, which was part of Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s 3rd Army, Wiedorfer saw combat for the first time that Christmas Day in 1944.

During the campaign for Bastogne, Belgium, his company was pinned down by enemy fire at the edge of a forest.

Near noon, Wiedorfer realized his platoon could not advance until the two German machine gun nests were destroyed. His 150-yard charge over a fresh 3-inch snowfall was made in a crouched position and in a hail of enemy gunfire.

“He slipped and fell in the snow, but quickly rose and continued forward with the enemy concentrating automatic and small-arms fire on him as he advanced,” the Medal of Honor citation reads.

He came within 10 yards of the first machine gun nest and hurled a grenade that instantly killed several Germans.

Then he jumped into the hole of the crew that he had just knocked out, quickly turned and emptied one clip at the second nest, killing three more soldiers and taking many prisoners.

Wiedorfer’s valiant charge left him unscathed.

“This heroic action by one man enabled the platoon to advance from behind its protective ridge and continue successfully to reach its objective,” the citation reads.

Wiedorfer was given a battlefield promotion that afternoon to sergeant, and a few minutes later, after the platoon’s leader and sergeant were wounded, he assumed command and led his men forward.

His other decorations included the Purple Heart and Bronze Star.

After being discharged from the Army in 1947, Wiedorfer returned to private life in Baltimore and his job as a power station operator. He was a supervisor of safety and training when he retired in 1981 from the power company.

In 2006, Wiedorfer told the Baltimore Sun, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the Medal of Honor didn’t exist because there were no wars and we could all live in peace? And that the only way to spell war was love? Wouldn’t that be wonderful?”

His wife, Alice, whom he married in 1943, died in 2008.

Surviving are two sons, a daughter, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.