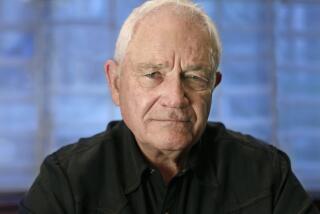

Sam Chwat dies at 57; actors lost, and learned, accents under dialect coach’s tutelage

Sam Chwat was a master of accents who taught Robert De Niro to talk like an Appalachian ex-convict, Olympia Dukakis to talk like a Holocaust survivor and Peter Boyle to talk like a bigot from the Deep South. A modern-day Henry Higgins, he also trained some actors to lose accents, helping Julia Roberts drop her native Georgia drawl and Tony Danza his distinctive Brooklynese. Chwat even turned his training on himself, muting his own “Noo Yawk” accent to prevent clients from miming the wrong cues.

Chwat, 57, who died of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma March 3 in Long Island, N.Y., ran the Sam Chwat Speech Center in New York City, which has helped thousands of people with speech challenges. His clients included corporate executives trying to eliminate distracting accents and politicians seeking to switch more nimbly between the voice they use in the halls of power and the one they use courting voters at home.

In the highly specialized world of Hollywood dialect coaches, Chwat’s background made him unique. While many of his colleagues have acting experience, he was a licensed speech pathologist who used the knowledge he gained working with stroke victims, stutterers and people with developmental disabilities to help actors fit their roles.

“He was very highly regarded,” Robert Easton, the dean of Hollywood dialect coaches, said of Chwat last week. “He went across the board” in the range of accents he taught.

Born in New York City on March 29, 1953, Chwat was a 1974 graduate of Sarah Lawrence College who earned a master’s in speech pathology from Columbia University in 1977. He started his professional life as a speech therapist working with patients in a New York hospital. He pronounced his last name without the “t” so it sounded like schwa, the linguistic term for a short, neutral vowel sound.

Around 1980 Chwat received a phone call from a major supermarket chain about an employee whose advancement opportunities were hindered by a thick Puerto Rican accent. His success with that client — who subsequently won a promotion — led Chwat to start a private practice.

His first Hollywood client was Andie MacDowell. She sought his help to avoid a repeat of her experience in the 1984 movie “Greystoke,” in which producers hired Glenn Close to dub over MacDowell’s lines because her South Carolina accent was deemed too intrusive.

Soon afterward, an unknown Roberts showed up in Chwat’s office. “Her manager said she would be eligible for a wider variety of roles if she lost her Southern accent,” Chwat told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2002. After working with Chwat several times a week for months, she landed her breakthrough role in 1988’s “Mystic Pizza.” He was so effective in eliminating linguistic traces of Roberts’ roots that she needed to be coached in a Southern accent for “Steel Magnolias,” the 1989 movie set in a small Louisiana town.

His most grueling assignment may have been coaching De Niro for the 1991 film “Cape Fear.” To prepare for his role as a convicted Appalachian rapist, De Niro had a researcher tape conversations with scores of violent felons in Appalachian prisons. Chwat reviewed each tape with De Niro until they settled on one voice that would serve as the actor’s model. Chwat devised a program of “sound substitutions” that De Niro used to replace elements of his New York-accented speech. He earned a best actor Oscar nomination for his work.

Some critics deemed Chwat’s next collaboration with De Niro less successful. He helped the New York actor flatten his A’s and sharpen his Rs to play a Seattle man in the 1993 movie “This Boy’s Life.” A New York Times reviewer disparaged De Niro’s accent for sounding “as if it had a lot of unexplained Irish in it.” Chwat fired back with a letter to the editor challenging anyone to find “any foreign pattern” in De Niro’s speech.

Over the years Chwat was frequently criticized for helping immigrants who wanted to sound more mainstream. Those critics accused Chwat of contributing to cultural homogenization, but he saw his services as an aid to assimilation for those who desired it.

His work took him all over the globe, said his wife, Susan Lazarus Chwat, who survives him along with three daughters and a sister. “He spent a month in Pakistan right before 9/11 working with call centers there,” she recalled in an interview last week. “They didn’t want people who called to know where they were. He helped them sound more American.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.