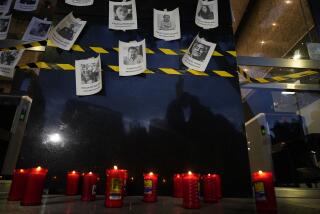

Respected Mexicali journalist who covered drug wars and social justice is found dead

After a fellow journalist was shot to death in 1997, Sergio Haro linked the killing to a local drug trafficker. Not long afterward, Haro found himself the target of anonymous threats — but he continued to report the story.

“Some people are telling me to stop writing about this, to run away, to disappear,” Haro, a Mexicali-based journalist, said at the time. “But that won’t solve a thing.”

Haro was found dead Tuesday at his home in Mexicali, according the Tijuana newsweekly Zeta, where he spent much of his professional life working as an editor and reporter.

The Baja California medical examiner’s office reported the cause of death as a heart attack. Haro was 60.

Born in the neighboring state of Sonora, Haro was one of Baja California’s most respected journalists, a familiar figure with his unruly mane of hair, wide smile and camera bag slung over his shoulder.

Colleagues from Zeta said that at the time of his death, Haro was at his computer, working on an article for Friday’s edition.

Haro’s career stretched over three decades, during which he covered a multitude of subjects, from the March 1994 assassination in Tijuana of a Mexican presidential candidate to the illicit capture of totoaba fish in the upper Gulf of California.

In his most recent published article, Haro wrote about payments by the Baja California government to the state’s media, “financially benefiting some media, individual reporters, and punishing others,” he wrote.

Haro was the subject of a 2012 documentary, “Reportero,” by New York-based filmmaker Bernardo Ruiz that explored the perils of writing about organized crime in Mexico.

Haro was part of a tightknit group of journalists who cover the region. One of his passions was writing about social issues, and he once spent months documenting the plight of migrant child labor in the Mexicali Valley.

Miguel Cervantes Sahagun, a longtime friend and fellow journalist, said Haro was profoundly committed to social justice. He believed that “in spite of the evolution of journalism, the aim must be social advocacy and exposing all that is rotten, or in the process of rotting,” Cervantes said.

Haro is survived by his wife, Zaida Montoya Mascareño, and their son, Luis Carlos Haro Montoya.

Dibble writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.