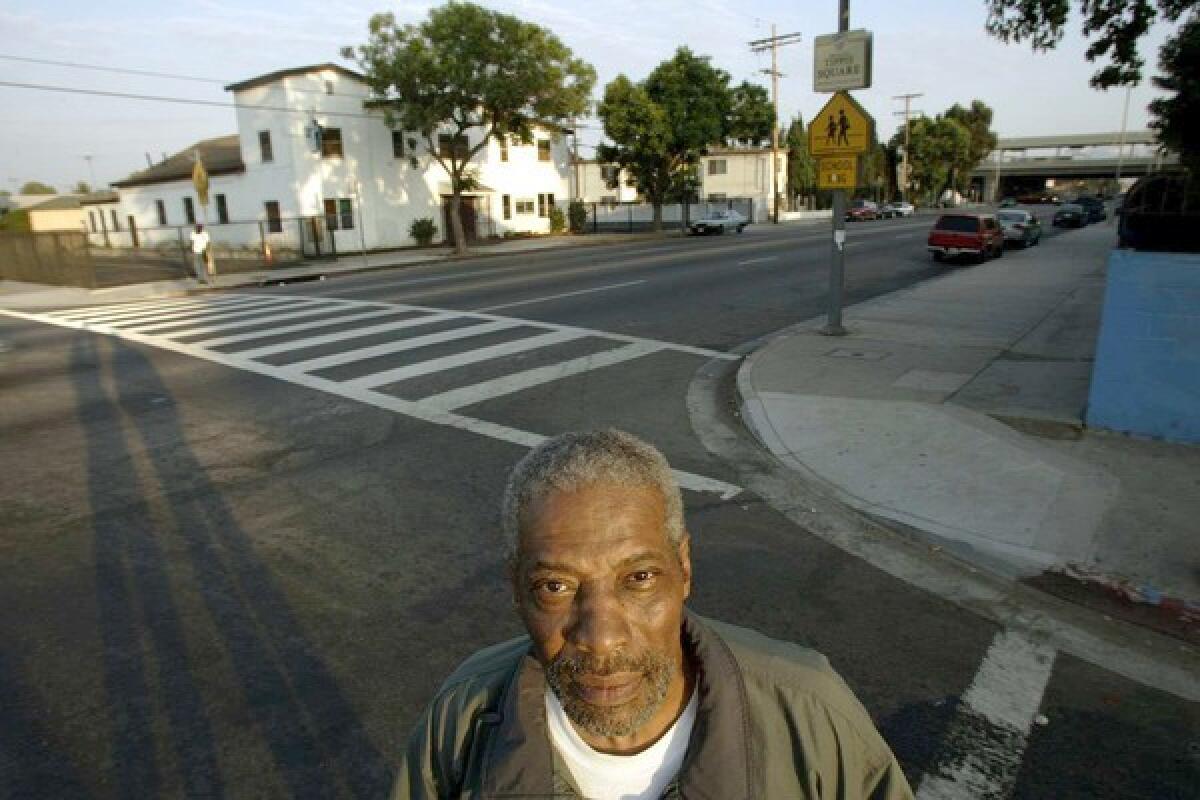

Tommy Jacquette dies at 65; South L.A. activist helped found the Watts Summer Festival

Tommy Jacquette, who channeled a simmering rage to become one of South L.A.’s most important social activists, died this week of complications from cancer, his daughter said. He was 65.

Jacquette died Monday at his home in Watts, not far from where the violence that shook his city began more than 40 years ago, an event that he said shaped his life of community organizing.

He helped create programs for youth in Watts, worked tirelessly with neighborhood groups and helped found the annual Watts Summer Festival in 1966. The festival symbolized the rebirth of a city and it helped influence several other black cultural events that followed.

“Tommy was an inspiration to me and to so many other people,” Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) said in a statement. “He was daring, fearless and bold, helping us to gain the courage to openly discuss and deal with race, discrimination and inequality in a way that few had been able to before.”

Jacquette was 21 in August 1965 when the arrest of a black motorist, Marquette Frye, sparked a weeklong riot -- to some a rebellion -- that left 34 people dead, 25 of them black, and more than 1,000 injured.

Four decades after the violence, Jacquette told The Times that he was simmering with rage that summer against a system he saw as racist. He had grown up with Frye and said that during the violence, he threw as many bricks, bottles and rocks as anybody and that his “focus was on the police.”

Jacquette said he was arrested, released the same night and rejoined the struggle. It was not a riot, he said, it was a rebellion.

“People keep calling it a riot, but we call it a revolt because it had a legitimate purpose,” he said. “It was a response to police brutality and social exploitation of a community and of a people, and we would no more call this a riot than Jewish people would call the extermination of the Jewish people ‘relocation.’ A riot is a drunken brawl at USC because they lost a football game,” he said.

“People said that we burned down our community. No, we didn’t. We had a revolt in our community against those people who were in here trying to exploit and oppress us,” Jacquette said. “Some people want to know if I think it was really worth it. I think any time people stand up for their rights, it’s worth it.”

Ayuko Babu, executive director of the Pan African Film Festival, said he met Jacquette in the winter after the rebellion, when they were both working for a neighborhood organization.

He said Jacquette looked inward and found what had enraged him. He began reading authors such as W.E.B. DuBois and later Stokely Carmichael and Frantz Fanon, trying to figure out how to best change his community.

“He understood that there was a direct connection between the Black Power movement, the civil rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael and him,” Babu said. “He actually responded to the historical call. A lot of people, the historical moment comes and they just stay on the sidelines and watch it go down the street,” he said.

Jacquette, who was born in Los Angeles on Dec. 13, 1943, helped create neighborhood programs for youth but is best known for his work with the Watts Summer Festival.

“He breathed it, he believed in it, he wanted everyone to bring their families and enjoy the day,” said his eldest daughter, Denise McFall.

Supporters say that the festival, which features black musicians and black cultural exhibitions, celebrates family and the statement that “black is beautiful” and helped prove that Watts is more than a stereotype of violence and apathy.

“Tommy created the festival to honor and celebrate our roots, our talents and our culture, and it subsequently helped to spark African American festivals across the country,” Waters said. “There will never be another Tommy Jacquette, and I know that the legacy he has left behind is enshrined not only in the Watts Summer Festival but in the larger community.”

Jacquette was intent on improving the community in his later years and worked for the U.S. Census, whose mission he believed in, and joined the anti-violence Watts Gang Task Force.

The task force brings together residents, politicians, social activists and police to work to solve problems in the community. About 40 years before he joined the task force, Jacquette was throwing bottles and rocks at police. Now he was sitting across the aisle from them, working hand in hand on issues of violence prevention and poverty.

Los Angeles City Councilwoman Janice Hahn said that having such a community legend -- someone who had lived through significant demographic and social and cultural changes in Watts -- at the weekly meetings helped bring people together.

“Tommy is a symbol of the past, present and future of Watts,” Hahn said, adding that Thursday’s City Council meeting was adjourned in his memory.

Jacquette is survived by his wife, Carmen Eatmon of Los Angeles; four sons, Derek and Raymond of Los Angeles and Damien and Juba of Phoenix; two daughters, Julienne Jacobs of St. Louis and Denise McFall of Los Angeles; his mother, Addie Young of Los Angeles; a brother, Bob Henson of Carmel; two sisters, Brenda Lake and Diane Young of Los Angeles; 23 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Funeral services will be private.

A public celebration of his life is scheduled for 10 a.m. Nov. 28 at the Watts Labor Community Action Committee headquarters at 10950 S. Central Ave., followed by a 1 p.m. repast at Ted Watkins Memorial Park, 1335 E. 103rd St.

Musician and Watts resident Ndugu Chancler said he will always remember Jacquette by his smile, walking down 103rd Street and “being really proud of the area and the community.”

What Chancler thinks people should remember from Jacquette’s life is “that there was a struggle that went on and there were people that never turned their backs on the neighborhood and were always pulling and fighting for the neighborhood.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.