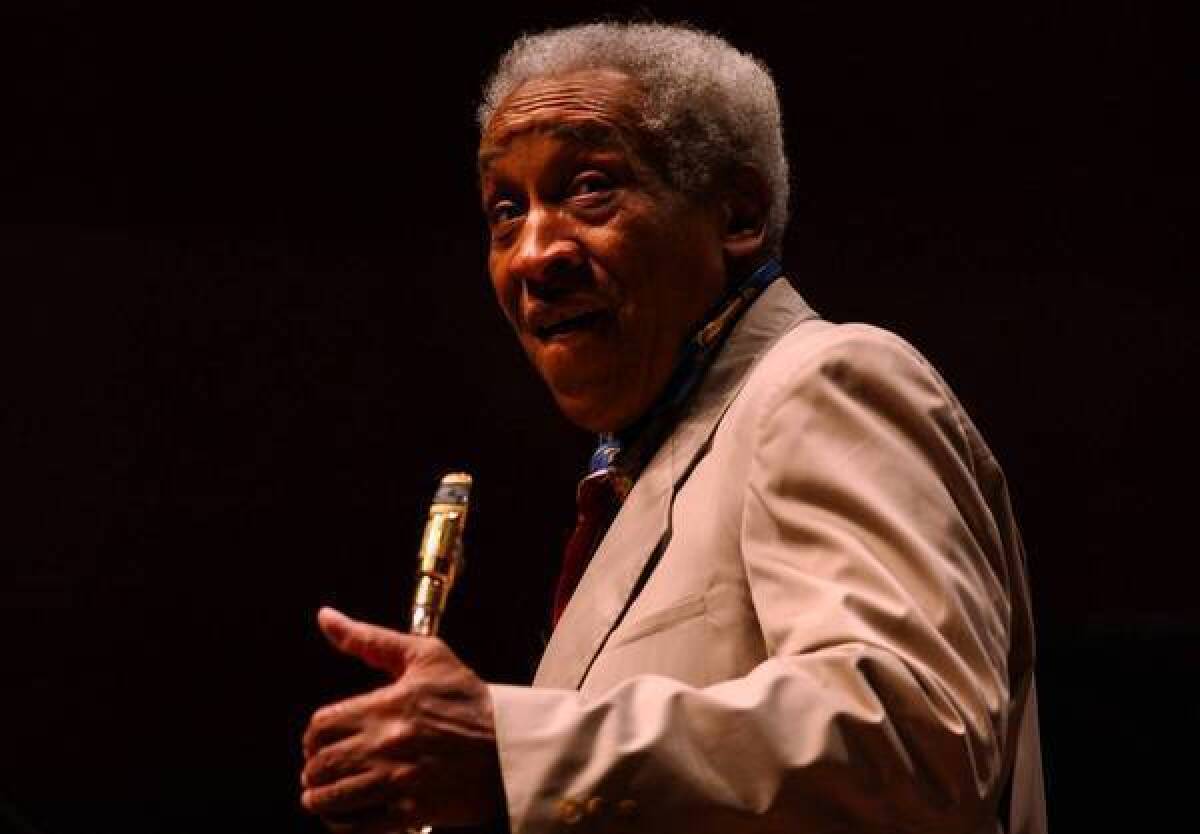

Von Freeman dies at 88; jazz tenor saxophonist with singular sound

Von Freeman was revered as a tenor saxophonist but was never a major star, worshiped by critics but perpetually strapped for cash. He seemed to purposely avoid commercial success. When trumpeter Miles Davis phoned Freeman in the 1950s looking for a replacement for John Coltrane, Freeman made a typical move — he never returned the call.

His refusal to leave his native Chicago during most of his career cost him incalculable fame and fortune but also enabled him to create a body of distinctive and innovative work. This year he received a Jazz Masters Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, regarded as the nation’s highest jazz honor.

He had mentored countless younger jazz musicians, including his son, Chico Freeman, who became more famous than his father as a tenor saxophonist.

Freeman died Saturday of heart failure at Kindred Chicago Lakeshore care center, said another son, Mark. He was 88.

His relative obscurity was a blessing, according to Freeman. It enabled him to forge an unusual but instantly recognizable sound and to pursue off-center approaches to his music.

When his “weird ideas” were criticized, it didn’t matter, Freeman told the Chicago Tribune in 1992: “I didn’t have to worry about the money — I wasn’t making” much. “I didn’t have to worry about fame — I didn’t have any. I was free.”

He represented the quintessential jazz musician, forging a unique and influential musical voice. He staked out an exotic but alluring artistic territory, merging elements of down-home blues, R&B; honking and brazenly avant-garde techniques. He was an utter master of bebop, the predominant jazz language of the 20th century.

“You hear one note, you know that’s his sound,” Fred Anderson, another noted Chicago tenor saxophonist, once said. “He took a lot from a whole lot of people and created Von Freeman.”

He was born Earle Lavon Freeman on Oct. 3, 1923. His mother played the guitar, and his policeman father was an amateur jazz trombonist who brought jazz musicians home from the club where he moonlighted as a bouncer.

After 7-year-old Von pulled the arm off the family Victrola, bored holes in it and turned it into a crude horn, his father bought him a saxophone.

By age 12, Freeman was playing professionally. When he debuted at a nightclub, his mother sent along a note that read in part: “Don’t let him drink, don’t let him smoke, don’t let him consort with those women….”

At Chicago’s DuSable High School, Freeman studied under the venerated band director known as Captain Walter Dyett, who was training a new wave of jazz talent that included Nat King Cole and Dinah Washington.

In 1940, Freeman played with Horace Henderson’s Chicago band before being drafted during World War II. He was soon performing with a Navy jazz band.

After the war, Freeman and his two jazz-playing brothers — guitarist George Freeman and drummer Eldridge “Bruz” Freeman — spent several years as the house band at Chicago’s Pershing Hotel. Von also played with future free jazz pioneer Sun Ra in the late 1940s.

By then, Freeman was a fluid improviser, a brilliant technician and, as always, a singular voice with a focused intensity.

At 49 in 1972, Freeman cut his first record as bandleader, “Doin’ It Right Now.” Like other Freeman releases of the ‘70s and ‘80s — “Have No Fear” and “Serenade and Blues” — “Doin’ It Right Now” captured the piquant quality of Freeman’s tone and the majesty of his soliloquies yet failed to find a broad audience.

His only taste of major-label success came in 1982, when Columbia Records released the album “Fathers and Sons,” featuring Ellis Marsalis with sons Wynton and Branford on Side A and Von and son Chico on Side B.

By the early 1980s, Freeman — who was nicknamed “the great Vonski” — was focusing purely on jazz and developing a cult following of fans who trekked to Chicago to hear the jazz giant once called “tragically under-recorded.”

Freeman is survived by his brother George; his sons Mark and Chico; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.