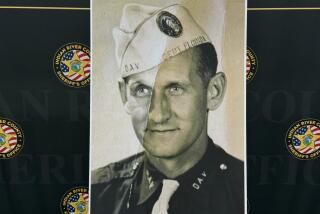

Walter Ehlers dies at 92; awarded Medal of Honor for WW II heroism

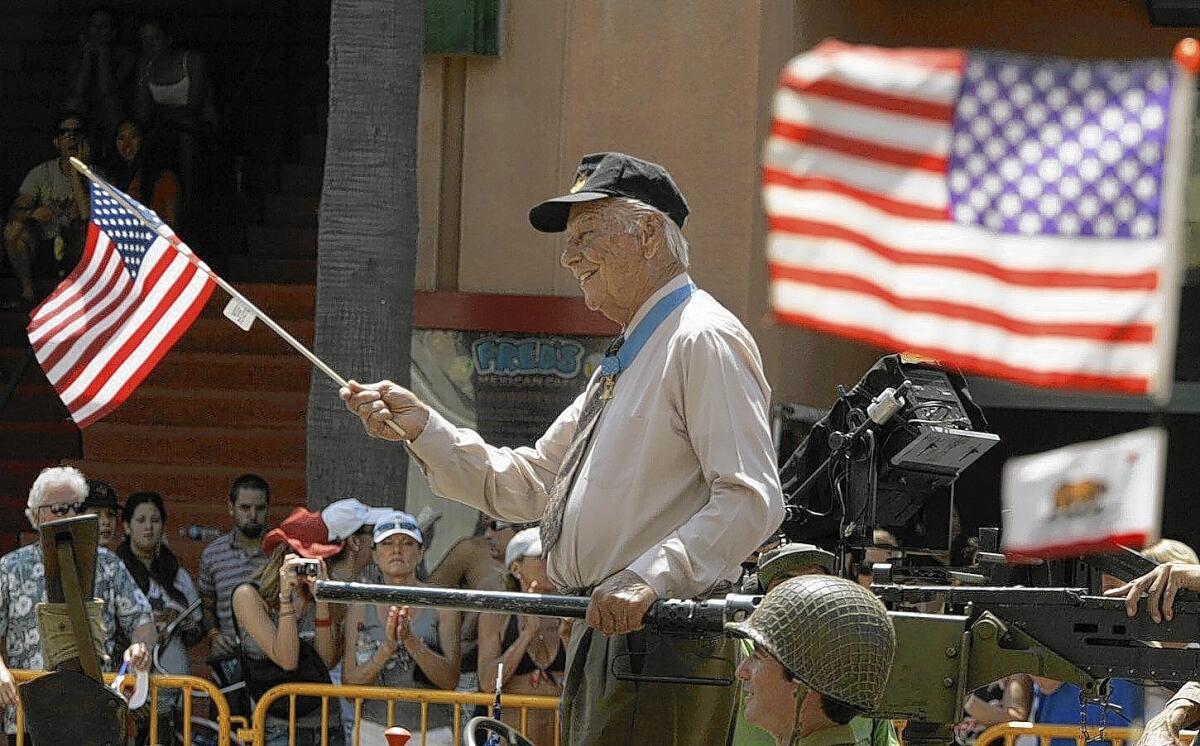

For extraordinary acts of courage during the D-day invasion of World War II, Walter Ehlers received the nation’s highest military award — the Medal of Honor. And it changed his life.

“I didn’t have a life before the medal,” Ehlers said in a 2004 Washington Post interview. A self-described “farmer boy” who not only took out enemy gun nests single handedly during the D-day operation, but also drew fire to himself so other soldiers could withdraw, Ehlers was invited to every presidential inauguration from Eisenhower on. He spoke all over the world to student, military and other groups. In Buena Park, where he where he lived after the war, a building was named after him and an action figure was made in his likeness.

But all the honors could not bring back his greatest loss during the war. His older brother, Roland, who was assigned to a different Army company, was killed on D-day.

“He was the bravest man I ever knew,” Ehlers told the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin in 2003. “My hero. Not a day goes by I don’t think about him.”

Walter Ehlers, 92, died Thursday at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Long Beach. The cause was complications from kidney failure, said his daughter, Cathy Metcalf.

With his passing, the number of living Medal of Honor recipients from World War II falls to seven, according to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, out of the 464 who received the award for actions during that war.

Walter David Ehlers was born May 7, 1921 in Junction City, Kan. He grew up doing farm work, but in 1940 he wanted to join the Army with his brother. Because he was underage he needed a parent’s permission and sought it from his mother. “She said, ‘I won’t sign unless you promise me you’ll be a good, Christian soldier,’ ” Ehlers said in a 2010 Orange County Register interview. “I never drank and I never smoked all the time I was in the service.”

After the United States entered the war, the Ehlers brothers fought together in the same unit in North Africa and Sicily. But as the D-day invasion in Normandy neared, they were separated to increase chances that at least one would survive. They saw each other in the assembly area not long before the invasion on Omaha Beach began on June 6, 1944. “We just told one another goodbye, and that was the last time I saw him,” Ehlers said in a 2009 NBC News report.

Ehlers, who was a squad leader and held the rank of staff sergeant, got his men safely off the beach and headed inland where they were to report on German troop activities. On the morning of June 9, near the town of Goville, the squad suddenly came under heavy fire. Ehlers ordered them to run for cover at a hedgerow and he “personally killed four of an enemy patrol who attacked him en route,” said the Medal of Honor citation. But the action was far from over.

He ordered his men to fix bayonets on their weapons and he moved out against enemy shooters. “I was ahead of my squad when I came upon a machine gun nest and knocked it out,” he said in a 1994 Los Angeles Times interview. Continuing on, “I came upon a mortar section with five or six people. That’s where my bayonet came in handy. They looked horrified and started running.” He went after another machine gun nest and “when he was almost on top of the gun,” the citation said, “he leaped to his feet and although greatly outnumbered, he knocked out the position single-handed.”

The next morning, the squad again came under heavy fire and a company commander ordered a withdrawal. “Ehlers realized that if someone didn’t provide cover, the Americans would be picked off one by one,” said an account of the action in the 2003 book “Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty.” He and another soldier climbed to a vantage point and started shooting at the enemy, “drawing fire on themselves as the rest of the platoon headed for cover.”

Ehlers was shot in the back by a sniper, but still managed to drag to safety his fellow soldier who was more seriously wounded. When Ehlers was treated, it was found that the sniper’s bullet had entered his side, hit a rib, then exited into his pack “where it pierced a picture of his mother, a bar of soap and his entrenching tool.”

A month later, according to the book account, he was told that his brother was killed on Omaha Beach. Ehlers found a private place, and then for the only time during the war he “went to pieces.”

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Ehlers received several other awards while in the service, including a Silver Star, Bronze Stars and Purple Hearts for injuries suffered.

After the war Ehlers worked as a benefits counselor for the Veterans Administration. But for the first 16 years on the job he didn’t tell coworkers that he had been awarded the Medal of Honor. They found out when the White House called him at work with an invitation to an event then-President Lyndon Johnson was hosting. Ehlers then accepted speaking engagements to tell his story and promote patriotism. In 1994 at the 50th anniversary of D-day in France, he spoke before a group that included President Clinton and Queen Elizabeth II of England.

Buena Park designated a building the Walter D. Ehlers Community Center. He was there in 2008 for a ceremony honoring World War II veterans. “I’m a very lucky soldier,” Ehlers told the crowd, as reported by the Orange County Register, “to have lived so long after the war.”

Ehlers is survived by his wife, Dorothy; daughters Cathy Metcalf and Tracy Kilpatrick; son Walter Jr.; sisters Leona Porter, Marjorie Justin and Gloria Salberg; 11 grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.