Wayne Dyer dies at 75; self-help expert wrote ‘Your Erroneous Zones’

When Wayne Dyer came out with his first self-help book in 1976, it was a dud, but he didn’t give up. He bought thousands of copies himself and crisscrossed the country, stopping at every small-town newspaper and TV station that would talk to him about his reader-friendly approach to achieving happiness.

His book — “Your Erroneous Zones” — ended up topping bestseller lists for 27 months.

Over the years, the book sold more than 35 million copies, and Dyer, preaching spiritually infused common sense about overcoming life’s obstacles, wrote more than 40 volumes that were variations on the theme. He also did seminars, lectures and retreats. He even published decks of cards — Inner Peace Cards and Power of Intention Cards — designed to help people leap past their fears and realize their dreams.

Dyer, who had homes in Maui and in Florida, died Saturday, according to a statement from Hay House, his Carlsbad-based publisher. He was 75.

No cause was disclosed, but Dyer was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2009. He later said he had received successful treatments from a Brazilian psychic healer named John of God.

Dyer’s family confirmed his death in a Facebook post: “Wayne has left his body, passing away through the night. He always said he couldn’t wait for this next adventure to begin and has no fear of dying. Our hearts are broken, but we smile to think of how much our scurvy elephant will enjoy the other side.”

Dyer frequently chuckled about the “scurvy elephant.” It was something an exasperated teacher had called him in grade school — but what she actually said was “disturbing element” and he had misconstrued it. For the rest of his life, though, Dyer relished the term, especially because he thought of himself as a disturber of the status quo.

Stop worrying! he urged his readers. Traditional psychotherapy was a “slick gimmick,” he said; if you want meaning and happiness and purpose, you won’t find it by dwelling on ancient parental slights or schoolyard upsets.

“Mental health is not complex, expensive, or involved, hard work,” he said. “It’s only common sense.”

Dyer expressed his can-do philosophy in prose that was frequently pithy. “When you change the way you look at things, the things you are looking at change,” the balding, telegenic Dyer told his audiences. “At every moment, you can either be a host to God or a hostage to your ego.”

Although some critics found his solutions simplistic — “It’s your life; do with it what you want” — Dyer was unfazed.

“I know it all sounds too simple to some people but what’s the other choice?” he asked a writer for Newsday. “To be unhappy with yourself? That’s the least effective choice of all.”

Dyer said he learned tough lessons in self-reliance as a boy.

Born May 10, 1940, in Detroit, Wayne Walter Dyer never met his father, who abandoned his mother and her three children shortly after his birth. Until he was 10, Dyer lived in foster homes and orphanages. By then, his mother had remarried and took him back in — but his stepfather was an abusive alcoholic.

“I was aware at age 10 that whatever happens to me, my own destiny was right in my own little hands and in nobody else’s,” he told fosterclub.com, an online organization for foster children. “That’s a liberating realization at any age.”

Dyer attended Wayne State University in Detroit and spent four years in the Navy. He was bored in the military, so he decided to read books. By the end of his tour, he had read 770 books, underlining unfamiliar words and looking them up at the end of each day.

He applied the same kind of discipline in his writing career. At one point, he wrote 60 essays on 60 of history’s “great self-actualizers,” including Pythagoras, Leonardo da Vinci, and Mother Teresa.

“I decided I could write the 60 essays in 60 days,” he told CNN in 2004. “I saw myself doing it. At the end of the day, I would do a gratefulness meditation. The next day, I would do it again.” The result was his 1998 book, “Wisdom of the Ages: 60 Days to Enlightenment.”

In 1970, Dyer received a doctorate in educational counseling from Wayne State. He was a high school counselor for several years before teaching at St. John’s University in New York, where he also gave popular motivational lectures. After a literary agent suggested he distill his lectures into a book, he wrote “Your Erroneous Zones.” It took two years to research, he later said, and 13 days to write.

Dyer followed with dozens of books whose titles are inspirational, including: “The Sky’s the Limit” (1980); “Real Magic: Creating Miracles in Everyday Life” (1992); “101 Ways to Transform Your Life” (1994); “Manifest Your Destiny: The Nine Spiritual Principles of Getting Everything You Want” (1997); and “It’s Never Crowded Along the Extra Mile: My Top Ten Secrets for Success and Inner Peace” (2001).

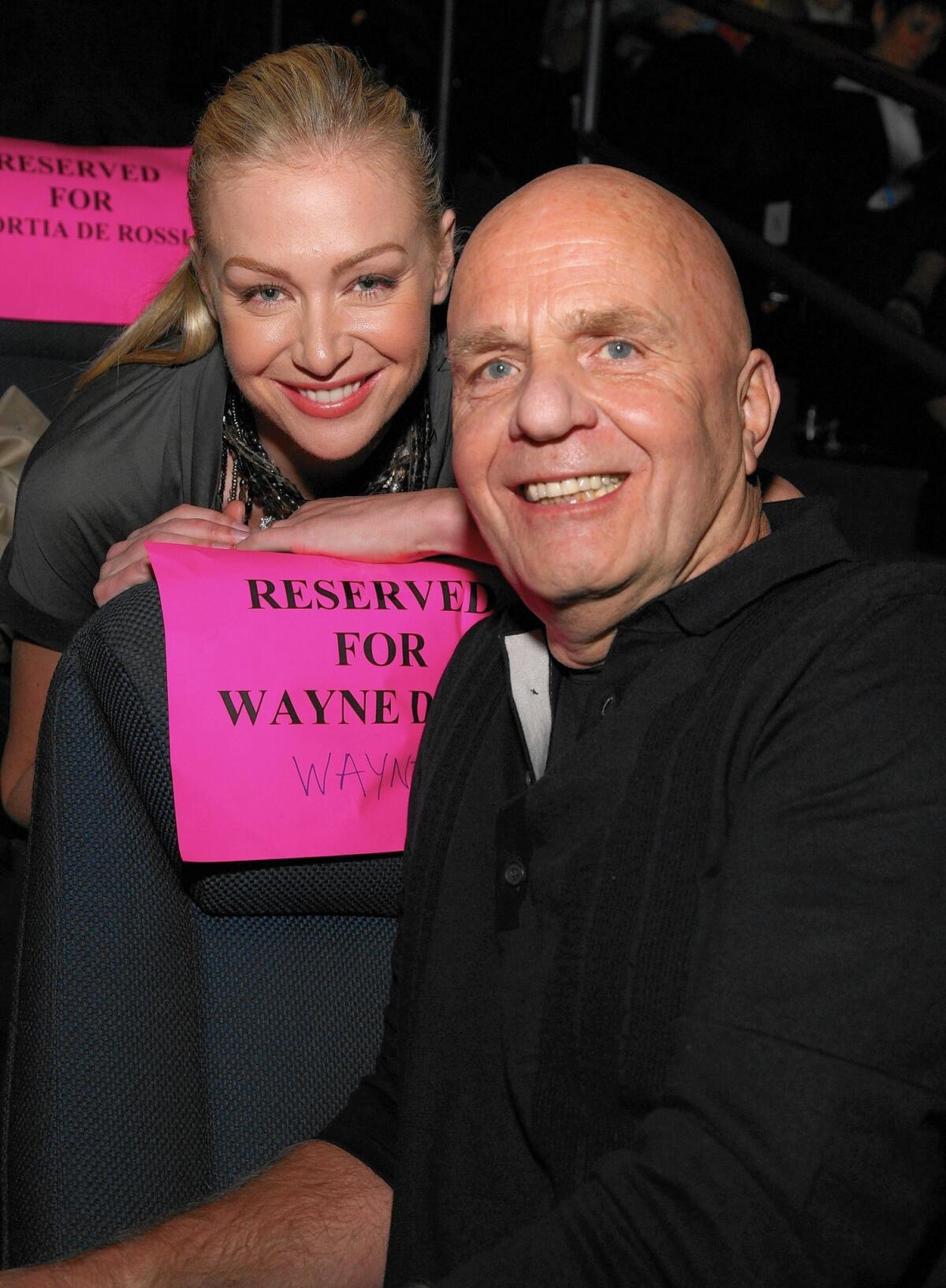

Offering insights about meditation, gratitude and forgiveness, he became well-known to TV viewers. Dyer was a guest on “The Tonight Show” more than 36 times. He was a friend of Oprah Winfrey’s and he officiated at the 2008 wedding of Ellen DeGeneres and Portia de Rossi. He was a fixture on PBS, for which he said he helped raise about $250 million.

In recent interviews, Dyer said he had become more spiritually conscious over the years. In 2014, he told the Maui News that the word “God” appeared just once in each of his first five books.

“At no time did I consciously switch,” he said. “It’s part of the dharma. Something else was involved. We all have a dharma.”

Dyer was married three times and had eight children. A complete list of his survivors was unavailable.

He had long said he was unintimidated by the prospect of dying.

“Your life is a parenthesis in eternity … a garage where you park your soul just for a few metaphysical moments,” he said on CNN in 1992. “Once you know that, then death doesn’t become something you’re afraid of.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.