Sheer determination

Architecture professor Dariouche Showghi was determined to build a smaller, more economic house for himself and his wife, and so the teacher became the student: He did his homework. There was a vacant lot for sale in Laguna Beach that no one wanted to buy. It was so steep, dropping 90 feet from street level, that it seemed impossible to build on. For months, Showghi sat on top of the extreme slope and studied it. He stomped up and down the solid bedrock and envisioned a tiered house cascading down the property, with ocean views from every room.

He had the ground tested by a geologist to make sure it was stable. Then he asked his son, Kurosh, a fine cabinetmaker by trade who climbs mountains for sport, to help him. Kurosh, 36, joked that it would be a “crash course” in construction, so he’d bring along his rock-climbing harnesses and ropes.

Showghi, 69, knew what he was getting into. He has taught structure courses and construction technology for 30 years at Cal Poly Pomona and has designed two other homes for his family, one on the same Laguna Beach street. This house, however, would be tricky.

“If it were any steeper,” says Showghi, “you’d have to carve into the rock and live in a cave.”

Building on an angle is expensive, time-consuming and dangerous. Machinery, materials and workers have to be hoisted up and down the site. One misstep and something crashes to the ground. A structural miscalculation can make the home uninhabitable. There is also intense design pressure. In addition to being safe, people have to feel safe and not as if they’re on the ledge of a skyscraper.

Yet Showghi was ready to accept the challenge. The key, he says, is to use the negatives to make a positive. He analyzed property values in the neighborhood, which reach into the millions. He considered that no one had faith in the weed-overrun, 60-by-140-foot lot. So he offered a puny $85,000 — and got it. Then he put his classroom lessons to work.

Last December, after two years of construction, he finished his house, a Lego-like contemporary on four levels: office and garage on the top; the main living area on the second; guest apartment on the third; and on the bottom, a design studio for Poly students visiting Showghi’s hands-on lab. Switchback stairs indoors and a long column of steps outdoors connect the floors.

The cost: $433,000, half the price of a comparable house on a flat lot.

“It was nothing,” says Showghi, who was born in Iran, married his wife, Gretha, in her Holland homeland and immigrated to the United States in 1967 with their two sons, Kurosh and Anush, who is now a real estate developer in Atlanta.

“Nothing to it?” says Kurosh’s wife, Paula. “That’s what we always hear from Pop.”

Showghi’s house is a textbook case of a knowledgeable do-it-yourselfer who spent every spare day on the site and every night planning the next day’s work. The crew was small: Showghi, his son and three laborers. When needed, they brought in specialists to excavate the land, erect the rigid steel frame, waterproof the decks and roof and install the plumbing, gas and electricity.

“We told them when we were hiring that we were picky,” says Kurosh. “But everything was so organized that they said it was their easiest job even though it was on the most difficult lot they’d ever worked.”

The concrete foundation was built like stairs, starting with the bottom floor, then working up. The street was 36 feet uphill from the foundation; sometimes Kurosh, who has climbed to the top of Mt. Whitney for fun, questioned whether they’d ever reach it. “There were many sleepless nights,” confesses Kurosh, who came home some evenings with chunks of concrete stuck to his socks. “Every day was a new challenge, like building an interstate bridge. It was a huge learning process.”

Before Showghi began his plans, he visited other lots on extreme slopes. Some, like the one next door to him, were littered with abandoned construction materials and trenches. They looked more like archeological ruins than future homes. He vowed not to repeat those mistakes.

He considered his house from every angle to make it safe from slides, fire and earthquakes. He also wanted it to be comfortable, beautiful and completed within his pinched budget.

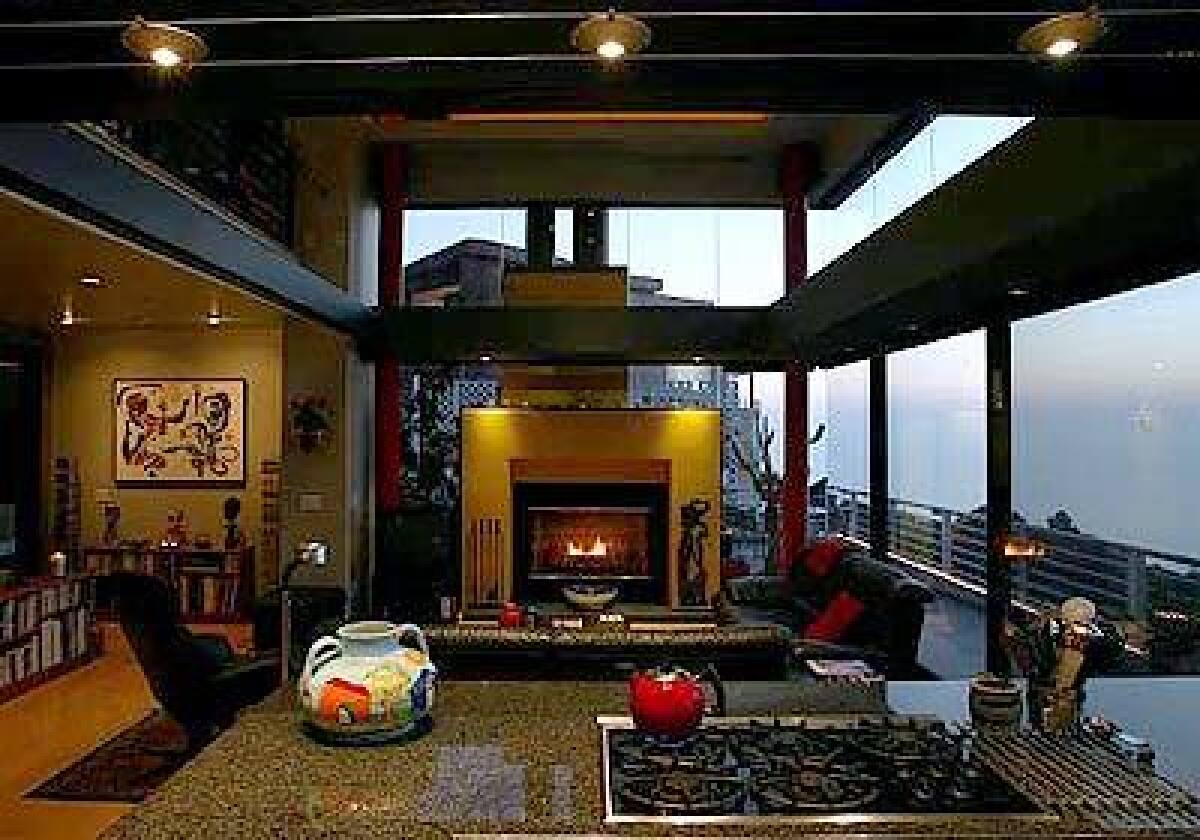

Inside, there is no feeling that gravity is being defied. Wide decks wrap around the house, blocking sight of the plunging yard. Instead, the view from every room is of the ocean, provided by story-high glass panels that even surround the fireplace in the living room.

“It’s a happy house,” says Gretha, standing in the entry next to a reproduction of architect Gerrit Rietveld’s “Red-Blue Chair” that was a gift from her husband’s students. In the living room, there is an antique Persian rug, and boxy red pillows dot the modern black leather sofas. A wall hanging of a Joan Miró painting brightens the dining room and colorful masks from Bali, Indonesia, South America and Oaxaca are displayed throughout the home.

Showghi finished the walls in black, gray and white, and exposed columns in prismatic yellow, red and blue. The colors as well as his use of straight lines, right angles and streamlined furniture pay homage to de Stijl, the abstract art and architectural movement of artist Piet Mondrian, Rietveld and others that influenced the Bauhaus and International Style movements.

When he was thinking through his plans, he spent hours on the site studying the patterns of the sun and breezes and gauging street noise. He used this information to his advantage. By reducing the length of his office on the top floor, he was able to direct the sun onto the lower decks all day long. Sliding-glass doors and windows were positioned to catch the ocean breezes, keeping the house cool without air conditioning. He placed the master bedroom underneath the thick concrete driveway, the quietest spot in the house.

A licensed architect and contractor, Showghi was able to make changes as needed. Before the walls were completed, he and Gretha sat in the Jacuzzi tub in the master bath and in pool lounge chairs in the other rooms to check out the views. From these vantage points, they could tell that the window next to the tub needed to be lowered so Gretha could see out of it without straining.

His main concern, however, was safety. He installed a drainage system to prevent water from pooling underground, which would undermine the slope, and chose steel and concrete that would flex during an earthquake. Concerned about brush fires, he planted succulents on the property and coated the exterior in stucco and other noncombustible materials.

“I’m not so arrogant to think that nature can’t do us any harm, but this house will sustain a substantial quake without collapsing,” he says. “There may be some glass broken and cracks in drywall. But really, nothing.”

He determined from geologist’s and structural engineer’s reports that only four well-placed caissons in the foundation of the 2,600-square-foot house were needed to secure it to the bedrock — an unheard-of number for a house built on a hill. Other hillside houses he studied typically used up to six times as many supports, spreading the weight out rather than concentrating it as he did.

“Some people think the solution to building on a slope is to drill and add more caissons, but that’s not necessary if the house is well-designed,” he says. “It cost me $21,000 for caissons and excavation and my neighbor, whose lot is not as steep as mine, cried on my shoulder because he’s spent $260,000 so far. It can cost a fortune if you don’t know what you’re doing. I’m not bragging. My motivation is to let people know that overblown costs are not normal.”

He also cut expenses by poring over pages of the Sweets Directory, the construction industry’s Sears catalog, to buy standard-sized materials rather than the more expensive custom-made ones, and renting used equipment and shoring devices that are typically tossed out at the end of a job.

The largest savings, though, came from labor. He and Kurosh worked alongside the workers, whom he paid by the hour, lifting, hammering and installing pieces.

At every stage, he checked the work against his blueprints.

The city of Laguna Beach limited the height of his house to 15 feet on the street side and 30 feet parallel to the sloping side. If not accounted for, layers of building materials can add up to a house that’s taller than its original plans. One on a flat lot can be off by a foot. On Showghi’s angled site, there was more opportunity for error. But after testing it, the surveyor was shocked to see that it grew by only one-eighth of an inch.

To Showghi, it was, well, not surprising.

“All we had to do was check and recheck and triple check each step,” he says. “It was nothing.”

He always says that.

*

(Begin Text of Infobox)

Make sure your builder’s on the level

*

Dariouche Showghi’s advice to homeowners before building on a hillside: Don’t skimp on hiring the best architect, structural engineer and either an engineering geologist or soil engineer. Each expert should be familiar with the area and follow the project from start to finish.

To find help, sketch out the size and scope of the project. Then draw up a list of prospective firms.

For recommendations, talk to homeowners who have had successful projects. Call your city’s building department for a list of local licensed professionals or check industry associations, such as the American Institute of Architects (www.aia.org), the Structural Engineers Assn. of Southern California (www.seaint.org/seaosc/index.asp) or the California Geotechnical Engineers Assn. (www.cgea.org).

Confirm they are licensed by the state. Contact the California Department of Consumer Affairs ([800] 952-5210; https://www.dca.ca.gov ) to view any black marks on their record and disciplinary actions.

Select two or more firms. Ask for references from previous jobs similar to yours. Call the reference to confirm their expertise in your type of project and their ability to complete projects on time and on budget.

Request a written proposal, including the cost and estimated completion schedule. There may be a charge for a preliminary visit.

— Janet Eastman

More to Read

Get the Latinx Files newsletter

Stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.