Glass Skyslide puts you above Los Angeles with 70 floors of nothingness below you

“A machine that makes the land pay.” That’s how architect and Manhattanite Cass Gilbert defined the skyscraper in 1900, when the building type was — ahem — just getting off the ground.

But the machine doesn’t pay like it used to, at least not when it comes to commercial skyscrapers that hold office suites instead of apartments or condos.

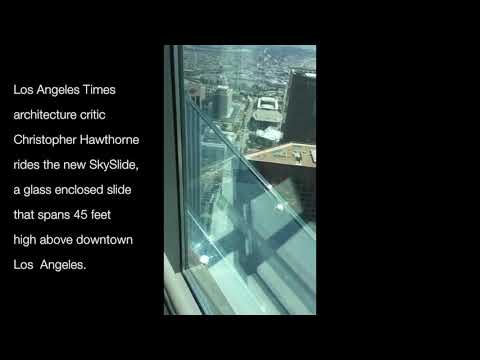

That’s one reason I found myself climbing onto a thin gray carpet Wednesday morning and careening down a steel-and-glass slide that has been attached — like a transparent worm, a see-through appendage — to the exterior of the tallest building in Los Angeles, the 1,018-foot-high U.S. Bank Tower.

After a trip that began on the 70th floor and spit me out rather unceremoniously onto a terrace on the 69th, it became clear why Singapore-based OUE Ltd., which bought the tower in 2013, expects a steady stream of visitors willing to shell out $27-$33 to experience the slide and adjacent observation deck.

Experience a different view of downtown Los Angeles on the US Bank Tower’s glass Skyslide.

The ride won’t exactly be a threat to Six Flags. Nor would I say I’m in a hurry to try it again. But it was an architectural experience, however brief, of a kind I don’t think I’ve ever had.

It’s also not tough to figure out why this particular tower is now topped by a major tourist attraction, which will open Saturday to the public. Designed by the architect Harry Cobb, a partner in I.M. Pei’s prolific firm, the building was originally known as Library Tower, for its downtown location across 5th Street from the Central Library.

Though it was more than 80% leased when it opened in 1989, by the time OUE scooped it up for $367.5 million three years ago the building was barely half full. And its problems are not unique: As white-shoe law firms shrink and expanding tech companies in L.A. increasingly move into restored warehouses or historic buildings, commercial skyscrapers around the country are struggling to find tenants.

That soaring vacancy rate gave OUE a pressing reason to rethink how the tower might be used. So did the fact that it will lose its title as the tallest building in the city when the new Wilshire Grand tower, topping out at 1,100 feet including its spire, opens next year.

In fact, as downtown Los Angeles — like many city centers in the U.S. — becomes more attractive as a place to live, the vast majority of new towers going up are largely residential. That leaves the owners of aging all-office high-rises like the U.S. Bank Tower looking for ways to produce new revenue — and, where possible, to redefine those towers in the popular imagination.

OUE is not the first company to see a possible revenue stream in the desire of adults to pay money to act like children in downtown settings. Bouncy-house urbanism is on the rise. In 2014 a company called Slide the City proposed a temporary, 1,000-foot-long waterslide for downtown Los Angeles, along Temple Street. The plan was canceled amid concerns it would waste water, or at least be in bad taste, in the middle of a drought.

The slide and observation deck are part of a $50 million makeover for the U.S. Bank Tower. Overseen by architecture firm Gensler, the new facilities also include a pair of redesigned lobbies (one for the tenants at ground level that is much more open to the sidewalk than before and the other for the slide-going public), a café, a slick and windowless “transfer floor” on the 54th story and a restaurant and bar on the 71st. The slide itself, called Skyslide, was designed by M. Ludvik Engineering.

In part because Cobb’s postmodern 1989 design for the tower was loosely based on Art Deco architecture, Gensler has chosen Deco motifs and a black-and-gold color scheme for many of the redesigned spaces.

Though it has overdone this tribute in certain spots — particularly the transfer floor, which looks oddly enough like a cross between a nightclub and, with its interactive displays, the Exploratorium in San Francisco — the new lobbies and the observation deck are restrained, with terrazzo floors and white walls.

Seemingly tailor-made for the age of social media, the facilities enter a market that is wide open in Los Angeles. The only observation deck of note downtown is one atop City Hall, which is free though (at 454 feet) quite a bit lower.

See what it’s like to ride the U.S. Bank Tower’s glass SkySlide — with 70 floors of nothingness below.

Tourists in other parts of the world have their pick of places to look out over the city. An observation deck at the World Trade Center tower in Manhattan — charging $32 per person — opened last year, joining one with a glass bottom and a ticket price of $22 at the Willis Tower in Chicago.

There is also one at Renzo Piano’s Shard in London at 26 pounds (about $38) a pop. And after buying a ticket package beginning at $71 you can walk out on a glass platform above the western edge of the Grand Canyon.

But in Los Angeles, a place that has been resolutely horizontal for nearly all of its architectural history, we have had very few chances that didn’t involve helicopter rides to become familiar with the top-down view.

The morning I visited was especially hazy, thanks to smoke in the air from twin wildfires in the San Gabriel Mountains. It was nonetheless possible to get a pretty clear look through the 7-foot-high glass balustrades at Walt Disney Concert Hall and Dodger Stadium to the north, the Hollywood sign to the west and the warehouses of the Alameda corridor to the south.

Two other elements are impossible to miss from up there: The amount of construction going on between Bunker Hill and the 10 Freeway and the number of buildings downtown topped by helipads. Those landing pads for Los Angeles Fire Department helicopters, marked by a telltale red circle, were mandated atop all new buildings higher than 75 feet beginning in the 1970s. The requirement, which essentially guaranteed a bland skyline packed with flat-topped towers, was finally scrapped; just before the official change the Wilshire Grand was granted a variance allowing its sloping crown.

I’d guess the law would have been dropped much sooner had the public had access to more views like the one that is now available at the U.S. Bank Tower. The tops of tall buildings were for many decades an easy place to stash bad policy in Los Angeles. That is no longer the case.

Considering that the observation deck has so little competition in Los Angeles — and that the slide has none, really — it’s tough to say precisely what kinds of crowds the remade tower will draw. Judging by the way OUE and Gensler have arranged the ticket desk and especially the transfer floor, it’s clear they are expecting long lines.

At the very least they are hoping to tweak Cass Gilbert’s old saying for a new age. If the office tower is no longer reliably a machine that can make the land pay, it just might be one capable of making tourists do so.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.