He’s No Longer a Lone Voice in the Conservative Wilderness. But the Letters, Columns and Books Keep Coming.

It’s been a half century since a young firebrand named William F. Buckley Jr. burst onto the political scene with “God and Man at Yale,” a scathing indictment of his liberal alma mater. By age 30, he had founded the conservative magazine National Review, which would become the bible of Ronald Reagan. By 40, he had his own television show, “Firing Line.”

Buckley, virtually alone, was the public face of political conservatism in the 1960s and ‘70s. He made it intellectually defensible. It became popular. It even became sexy. And Buckley became a cultural icon.

The firebrand quietly turns 76 this year. “Firing Line” is gone after three decades on the air, the longest-running show with the same host in TV history. Buckley is off the lecture circuit he once rode to win converts to the right. He barely knows the current occupant of the White House, a self-described “compassionate conservative,” having seen him “maybe two or three times.”

New generations of conservative intellectuals now fill think tanks. They write for his National Review but also the Weekly Standard and the Wall Street Journal editorial page. “It’s not lonely the way it was 45 years ago,” Buckley says, “when there was really nothing, certainly no journal of opinion on conservative thought. There are tons of people here now.”

So what’s an icon to do? Buckley has returned to his roots, to the keyboard over which his fingers have long danced. Whether working out of his Upper East Side apartment in New York or the converted garage of his Stamford, Conn., home, Buckley is writing at a tremendous rate. He’s writing e-mail--to friends, to fans, to foes and even, a few times, to the author of this article. He’s writing letters. He’s writing two columns a week. He’s writing books at a pace of one a year.

And, of course, he’s busy being himself--an urbane, charming sage. “He’s being Bill Buckley 24 hours a day, and that’s part of what his job is,” says Sam Tanenhaus, who is writing a new biography of him. “That’s not something you can retire from.”

Time was, Buckley could be counted on to rise eagerly to every challenge in the political arena. But, like an aging lion, he isn’t so easily drawn into battle these days. He no longer follows current events with the passion that he once did. He is, as one friend says, serene. Or, to use a word secure in Buckley’s vocabulary, irenic. A promoter of peace.

But he can still mix it up. Consider Buckley’s response to a review for his last novel, “Spytime: The Undoing of James Jesus Angleton.” Some critics liked the book. But others didn’t; and one, Eric Tarloff, was unusually blunt.

“Something must be said,” Tarloff wrote in his review last year for the New York Times. The erotic scenes in “Spytime” are “like passion observed and described by an alien . . . exceptionally finicky life form.” Tarloff treated his readers to a few of those scenes and pronounced them so bad “that they’re far and away the most enjoyable part of the book, by themselves almost reason enough to justify a recommendation.”

Now, it must be said that Tarloff knows something of this territory. In his first novel, “Face Time,” Tarloff’s protagonist is a presidential speech writer who is cuckolded by the president of the United States. In his second, “The Man Who Wrote the Book,” his hero is an English professor who writes a dirty book.

Tarloff also couldn’t be more different, politically, than Buckley. Buckley once raced to the defense of Joseph McCarthy’s campaign against Communists in the U.S. government; Tarloff’s father, a screenwriter, was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. Tarloff has been a speech writer for Bill and Hillary Clinton, and Tarloff’s wife was once Clinton’s chief economic advisor.

When Buckley sat down at his keyboard to reply, the result was stylish, tart and witty:

“Having egregiously misread the plot, Mr. Tarloff goes on to amply excerpt from erotic passages in my novel, on which excerpts I would comment except that merely to pass my eyes over them brings on such ardor as to leave me immobilized.”

Buckley, smoking a Dutch cigar in his Manhattan apartment, chuckled as he recalled the letter. “Maybe I need to take a course in erotic writing,” he says, arching his famous eyebrow.

Writing and language have always been Buckley’s passion. He grew up in a house where erudition was prized. His father, an oilman, saw to it that the Buckley children learned French and Spanish from nannies and sojourns abroad. They practiced concertos at the piano and political argument at the dinner table.

By the time he turned 50, in 1976, Buckley was one of the 20th century’s best-known public intellectuals, a Renaissance man of the right. He was doing his television show, lecturing across the country and appearing in debates on network TV. He had written nonfiction books about everything from politics to sailing, and his use of words--especially rare ones--sent readers and listeners to their dictionaries. As Samuel Vaughan, his editor, put it a few years ago: Buckley’s use of language elicits “both exasperation and admiration.”

It was also at age 50 that Buckley added two pursuits to his repertoire--he took up the harpsichord and became a novelist. He developed a passion for the harpsichord after his younger brother sent him one as a gift. But now it’s the source of some regret. “I’ve performed nine times in public,” he says. “But after the ninth time, I realized I was just not good enough. Among other things, I was so frightened--God, I was so frightened--that I made mistakes that I didn’t make when I practiced. I just don’t have the natural prowess. So I hardly play anymore.”

His first attempt at fiction was more successful. As Buckley tells it, he was pressured by Vaughan into attempting a novel. “I told him how much I was enjoying reading ‘The Day of the Jackal’--a terrific book--and Sam said to me, ‘Why don’t you write a novel?’ ” Buckley recalls. “And I said, ‘Sam, why don’t you write a trumpet concerto?’ ”

But a contract materialized the next day, and Buckley agreed to try it: 100 pages for one-third of the advance. The result was a bestseller, “Saving the Queen,” the first of 10 novels featuring the dashing CIA agent Blackford Oakes (and Buckley’s first sex scene, with Oakes taking a young Queen of England to bed).

This summer, Buckley’s 14th novel, “Elvis in the Morning,” leaves the spy game for unusual new territory: Elvis Presley and the student radicals of the 1960s. In “Elvis,” Orson Killere, a young American growing up on a U.S. Army base in Germany, falls under the spell of a socialist professor and the music of Elvis Presley, then a soldier in Germany. When caught stealing Presley records to give away, Orson is befriended by the singer. The two stay close as their lives unfold--Orson as a student protester and drifter, and Elvis, of course, as a cultural icon.

At first blush, this would seem to be unfamiliar terrain for Buckley. During the ‘60s, Buckley was an unabashed anti-Communist who once described Vietnam protesters as “young slobs.”

But as John Judis points out in his 1988 biography of Buckley, this champion of the right has a tolerant, even inquisitive attitude toward the counterculture. He’d ride a motorcycle through the streets of New York, his fashionably long hair blowing in the wind. He printed favorable articles on the Rolling Stones and the Grateful Dead in National Review, to the dismay of his ideological soul mates. And his libertarian instincts would lead him, in 1972, to come out for decriminalizing marijuana, which he boldly announced that he had sampled while on a sail into international waters, beyond the reach of American law.

“I wanted to write a book about a young American who turned left and what kind of experiences the Woodstock generation had, the going on the road and so on,” Buckley says. “And when I sat down to do it, I bumped into the omnipresence of Elvis.” Buckley never met Elvis, but he says he’s since become a fan. “The trouble with buying an Elvis Presley record is there are going to be eight awful things and two or three really good things,” he says. “The good things are terrific, though. He was a great balladeer.”

On a recent rainy afternoon, Buckley settles into a chair in his Manhattan apartment and ruminates on retirement, books, the state of the conservative movement and his legacy. The room is comfortably stuffed with dark red furniture. Buckley is clad in a sweater and button-down shirt; his penny loafers rest on an animal-skin rug.

He spends a day or two a week in this Upper East Side apartment, a two-floor maisonette once owned by the late U.N. Secretary Dag Hammarskjold. Every other Monday, he hosts the editors of National Review for dinner here. Most of the week, though, he stays at his 15-room, Mediterranean-style villa on three acres sloping to Long Island Sound in Connecticut. He and his wife, Pat, have owned it half a century.

Buckley began paring down his prodigiously busy schedule two years ago. Four months after the 1,429th--and last--episode of “Firing Line,” in December 1999, he gave his final public speech. Stepping down from the podium “feels wonderful,” he says. “I don’t miss it at all.”

“Firing Line” had made Buckley a hero to the right and a villain to the left. As Norman Mailer wrote him in the 1960s: “I think you are finally going to displace me as the most hated man in America. And of course the position is bearable only if one is No. 1.” At the show’s peak, with an Emmy to its credit, no serious public figure, from heads of state to Hugh Hefner and Muhammad Ali, could afford to pass up the invitation to do battle with Buckley.

He still writes his syndicated column, though down from three times to twice a week. And while it’s no longer must-reading in Washington, it can still surprise. Earlier this year he took on the sensitive matter of the arrest of President Bush’s 19-year-old daughters for attempting to buy booze on a fake ID. While many columnists used the occasion to lament the troubling rise of alcohol abuse on campus, Buckley drew a different conclusion: The drinking age, he said, should be lowered from 21 to 18.

Buckley keeps an eye on National Review, which retains a healthy circulation of 160,000. (It’s an irony of the publishing world that having a conservative in the White House tends to dampen circulation for conservative magazines. National Review had a circulation of 250,000 during the Clinton years). The magazine is Buckley’s enduring legacy. He’s kept it afloat for 45 years with his speaking fees and annual fund-raisers, and he says it’s set for the future. “We’ll be around long after you’ve written my obituary,” he says.

Buckley’s interest in the day-to-day skirmishes in Washington, though, has waned. “There was a time when he was firing away on all issues at all comers,” says Evan Galbraith, a longtime Buckley friend, onetime ambassador to France and member of the National Review board. “But I suppose you could say he’s mellowed now that his agenda is less.”

And that has left more time for writing. He spends hours on personal correspondence, which Buckley regards as a sacred duty. “I get mad at my friend [book critic] John Leonard because he never answers a letter. Never, ever, ever. I can’t imagine not replying to mail,” Buckley says.

He even exchanged letters in the online magazine Slate earlier this year with his personal friend and political foe Michael Kinsley, Slate’s editor. The subject wasn’t politics; it was a tongue-in-cheek argument over forms of address. Mike versus Michael. Bill versus William.

Buckley is working on rewriting his 15th novel--and his 41st book. Titled “Nuremberg--The Palace of Justice,” it concerns the relationship between an interpreter and a defendant at the post-World War II Nuremberg trials. The bulk of the writing was completed during Buckley’s annual winter vacation in the Swiss Alps.

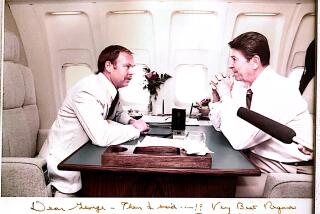

The high point of Buckley’s influence in Washington was 1980, when Ronald Reagan took office. The two had known each other for years; in 1967, Buckley wrote a profile of Reagan for West, an early incarnation of this magazine. What Buckley brought to right-wing politicians of Reagan’s era was, in George Will’s words, “intellectually defensible modern conservatism.”

Buckley no longer needs to play that role in American politics. And while his magazine endorsed George W. Bush over John McCain in the Republican primaries last year, Buckley hasn’t been completely won over by the new president.

“The big question is whether Bush has the charismatic authority to go out and generate support for his positions,” Buckley says. “There is something working for him, a wholesomeness. But whether, in a year from now, he will have established himself as a really important presence is, I think, an open question.”

Dozens of writers and thinkers occupy the political right these days. But none has the combination of intellectual heft and public charm that made Buckley a celebrity.

“Bill is a generational phenomenon,” says Tanenhaus, the biographer. “He’s part of that generation of writers--Mailer, Capote, Vidal, Styron, Baldwin--who rose to prominence at the same time. They were philosopher kings, men of letters whose themes and interests were political.”

In the realm of political debate, time has a way of putting old arguments into perspective. Disagreements become honorable. Adversaries are reminded of their mutual respect. History is reconsidered. After all, the republic has survived.

The Kennedy family recently gave Gerald R. Ford its John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage award for pardoning Richard Nixon in 1974. Buckley remains close to many of his liberal combatants, such as John Kenneth Galbraith. And Yale recently gave Buckley an honorary degree--marking a career that was launched with a relentless attack on that university.

Back in 1976, when Buckley was signing copies of “Saving the Queen,” he would often write an inscription intended to describe Blackford Oakes, his dashing protagonist. It seems now, 25 years on, to be Bill Buckley’s own legacy:

“A tale of a simple republican, doing his duty.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.