Dr. Jean Dausset dies at 92; scientist’s discovery made tissue typing for transplants possible

Dr. Jean Dausset, the French Nobel laureate who discovered the human leukocyte antigen, or HLA, system on human tissue that made tissue typing for transplants possible, died June 6 in Mallorca, Spain. He was 92.

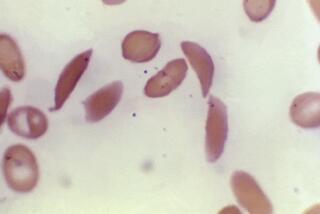

The HLA antigens are molecules on the surface of cells that allow an individual’s immune system to distinguish between its own tissues, which it ignores, and foreign tissues, which are vigorously attacked by disease-fighting antibodies. There are six major HLA groups, but hundreds of variations within them, so it is virtually impossible to produce a perfect match in transplants. That is why immune-suppressing drugs must also be used to prevent rejection even with the best matches.

In other animals, these antigens are called histocompatibility (“histo” meaning tissue) antigens. These were first discovered in mice by Dr. George Snell of the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, who shared the 1980 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Dausset and Dr. Baruj Benacerraf of the Harvard Medical School.

Dausset discovered the histocompatibility antigens in humans, gave them the name HLA, and demonstrated with experimental skin grafts that incompatibility of antigens led to rejection of transplants. He and his colleagues collected blood samples from people from 54 racial and ethnic groups from all corners of the world and demonstrated that the HLA complex was not unique to any particular group, but was universal.

He then showed that the genes that serve as the blueprints for the antigens reside in a section of chromosome 6 known as the major histocompatibility complex. He also demonstrated that many of the genes were linked to specific human diseases.

With his Nobel Prize money and a substantial grant from French television, he established the Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain, or CEPH, for the study of the human genome. The center collected DNA from 61 large families and made it available to researchers around the world who made a map of DNA markers that played a crucial role in deciphering the human genome.

Jean Baptiste Gabriel Joachim Dausset was born Oct. 19, 1916, in Toulouse, France, the son of a physician who moved the family to Paris when Jean was 11. He earned a bachelor’s degree at the Lycee Michelet in Paris and enrolled in medical school at the University of Paris, but was drafted into the French army in 1939.

After France fell to German troops in 1940, he made his way to the Free French Forces in North Africa, after first giving up his identity papers to help save a Jewish colleague. During the Allies’ Tunisian campaign, he performed transfusions, triggering a lifelong interest in hematology that led directly to his Nobel.

After Paris’ liberation in 1944, he returned to the city and was placed in charge of blood collection for the regional transfusion center. He completed his medical studies in 1945. After a postdoctoral fellowship in Boston at Children’s Hospital he returned to the regional blood center, where he began transferring the techniques developed for matching red blood cells to the study of white blood cells.

While continuing his research, he collaborated with Dr. Robert Dubré to institute radical reforms in the hospitals and universities where medicine was taught, emphasizing the need for professors of the basic sciences and laying the foundation for further French advances in biology.

He also founded France Transplants and France Bone Marrow Grafts, organizations dedicated to delivering donor organs and bone marrow to needy recipients quickly and efficiently.

In 1993, CEPH became the Foundation Jean Dausset-CEPH. Dausset retired as president in 2003 but remained honorary president until his death.

Dausset had a lifelong interest in what he called “plastic art” and at one time was owner of an Impressionist gallery, Le Gallerie du Dragon.

In 1963, he married Rose Mayoral from Madrid and they had two children, Henri and Irene. He is survived by all three.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.