Dr. Mahlon Hoagland dies at 87; scientist helped discover how cells build proteins

Dr. Mahlon Hoagland, who helped unravel the mystery of how cells build proteins by discovering a molecule that brings individual amino acids to growing protein chains and who spent the latter part of his career explaining biology to the public in a series of well- received books, died Sept. 18 at his home in Thetford, Vt. He was 87.

FOR THE RECORD:

Hoagland obituary: An obituary of biochemist Mahlon Hoagland in Section A on Oct. 17 said that James Watson and Francis Crick shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for discovering the structure of DNA. Maurice Wilkins also shared in the prize that year. —

He had been suffering from cardiovascular disease and kidney failure and chose to abstain from food and drink to die peacefully, lingering for nine days with his family at hand.

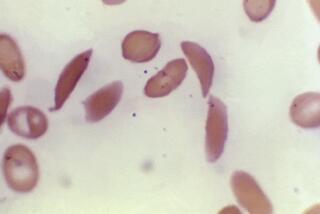

A physician turned biochemist, Hoagland was a key participant in the heady days during which the role of DNA in the cell finally became clear. Working with Paul C. Zamecnik at Massachusetts General Hospital, he discovered transfer RNA, commonly called tRNA, a key player in the complex process by which genetic information contained in DNA is translated into proteins, the functional and structural components of cells.

“He and Zamecnik deserved to win the Nobel Prize for their fundamental work on tRNA,” said biologist James Watson, who shared the Nobel with Francis Crick for discovering the structure of DNA.

When Hoagland began working at Massachusetts General in the early 1950s, Zamecnik had already developed a cell-free system from rat livers that could synthesize proteins. When the pair added radioactively labeled amino acids to the system, they discovered that radioactivity was soon found throughout the mixture. But when they stopped the process quickly, they observed that it was concentrated in large structures called ribosomes, which were soon identified as the site of protein synthesis.

In 1956, they reported that amino acids to be added to the growing protein chain had to be activated so they could form a chemical bond with the chain. They found that this activation involved adding adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, to the amino acid, making it highly reactive.

Two years later, they reported the discovery of tRNA, which binds to individual amino acids, marking them for identification by the ribosomal machinery so the correct amino acid is added at each stage of construction. In 1960, Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner showed that genetic information was ferried from nuclear DNA to the ribosome by a different molecule, called messenger RNA, completing our understanding of the process.

In his later career, Hoagland studied the carcinogenic effects of beryllium, the biosynthesis of coenzyme A and the mechanisms by which the liver is regenerated.

Mahlon Bush Hoagland was born Oct. 5, 1921, in Boston. His father was Hudson Hoagland, who, with Gregory Pincus, co-founded the institution now known as the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology. Noting the amount of time his father spent embroiled in research, young Mahlon decided to become a physician instead, enrolling in Williams College, then transferring to Harvard University after a year.

Because of the war needs, he was placed in a program that allowed him to enter medical school without getting his undergraduate degree, and he received his M.D. in 1948. He had planned to become a surgeon, but a bout with tuberculosis not only kept him out of the military, it also shunted his career plans toward research. He joined Massachusetts General after his graduation.

In 1970, he moved to the Worcester Foundation, where he served as scientific director for 15 years before retiring in 1985.

In the mid-1970s, Hoagland organized a group of distinguished scientists, including several Nobel laureates, who descended on Congress to argue that funding basic research was the best way to ensure medical advances. The effort led to increases in support for such fundamental research.

Hoagland had always argued that teaching was as crucial to scientific advancement as research and had disparaged many textbooks as needlessly complicated. After retiring, he teamed with artist Bert Dodson to create “The Way Life Works,” which combines whimsical watercolors with concise explanations of scientific discovery and received the American Medical Writers Book Award in 1996. A follow-up textbook was titled “Exploring the Way Life Works.” He also wrote four other books on biology for the general reader.

A talented sculptor of wood, Hoagland produced more than 40 pieces, many of which showed women climbing on various objects. One creation was a DNA double helix with children climbing up the spirals.

His 1943 marriage to Elizabeth Stratton, which produced four children, ended in divorce. He subsequently married bookseller Olley Virginia Jones, who died earlier this year. A daughter, Susan, died in 1973.

He is survived by two daughters, Judy Hauck of Wilmot, N.H., and Robin Hoy of Brunswick, Ga.; a son, Mahlon “Jay” Hoagland Jr. of Rockport, Maine; five stepchildren; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.