Supreme Court may reconsider what is ‘violent felony’ in ‘80s-era law

The Supreme Court served notice Monday it is ready to reconsider the reach of a 1980s-era law that imposes an extra 15-year prison term on “armed career criminals.”

The justices are not troubled because these mandatory prison terms are too stiff. Instead, they voiced concern with the law because it is not clear what crimes trigger the extra punishment.

For example, does a past conviction for drunken driving, child abuse or possession of a sawed-off shotgun count as a “violent felony” on a criminal’s record?

The argument Monday suggested this may be the rare instance in which the high court strikes down a criminal law, at least in part, because it is so vague as to be unconstitutional.

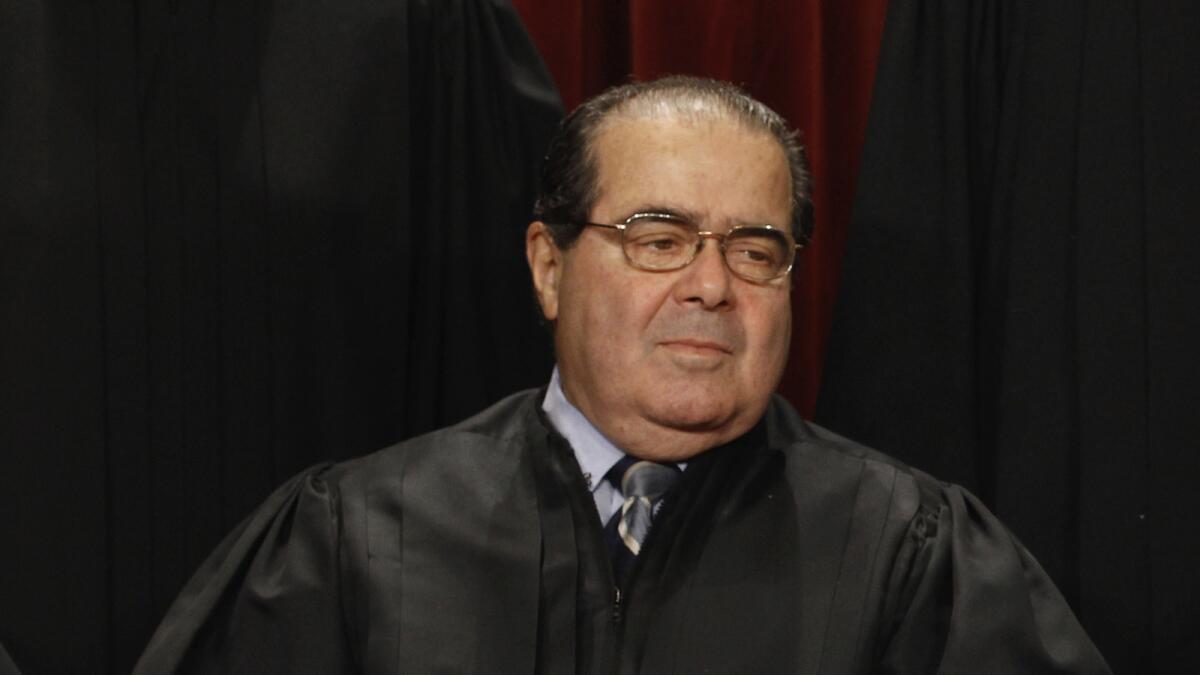

In recent years, Justice Antonin Scalia has insisted Congress make clear who is covered by the Armed Career Criminal Act of 1984, and he pressed that view again Monday.

“Can we just patch up this statute?” he asked skeptically of a government lawyer. “It seems to me it has to be done by Congress.”

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan have agreed with Scalia, but it was not clear during the argument whether a five-member majority will strike down the law.

Justice Samuel Alito led the defense of the disputed provision. If its meaning seems confused, he said, it could be because the court “messed it up.”

Congress passed the law amid the “war on drugs” of the 1980s, a time when mandatory minimum prison terms were the favored tool of lawmakers. People who were convicted of unlawful possession of a firearm would receive a mandatory 15 years in prison if they had on their record three convictions for a violent felony or a serious drug crime.

As examples of violent crimes, the law cited burglary, arson, extortion or the use of explosives. But it then described other “conduct that presents a serious potential risk of physical injury to another.”

The last phrase has puzzled trial judges as well as the high court.

In 2008, the court said a drunk driving conviction did not count as a violent felony because the motorist did not intend to cause violence. But in 2011, the justices decided that fleeing from the police in a vehicle did count as a violent felony because, like a burglary, it could lead to a violent confrontation.

The case heard Monday concerned Samuel Johnson, a white supremacist from Minnesota who was arrested after telling an FBI undercover agent that he had homemade explosives and had picked out several targets. He was found with an AK 47 rifle and a .22 caliber semiautomatic handgun.

He pleaded guilty to the gun possession charges, and a federal judged sentenced him to 15 years in prison because he had three “violent felonies” on his record. They included one robbery count, one count of attempted robbery and possession of a sawed-off shotgun.

Johnson appealed the sentence on the grounds that possessing a short-barrel shotgun was not a violent felony.

Katherine Menendez, a federal public defender from Minneapolis, urged the court to strike down the part of the law that allows judges to decide which past crimes are subject to the law.

Congress “did not set out with clarity what predicate offenses fall within its coverage,” she told the court.

If the court agrees with her in Johnson vs. United States, its decision could give hundreds of federal inmates grounds for challenging their prison terms.

On Twitter: @DavidGSavage

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.