In 1969, Democrats and Republicans united to get rid of the electoral college. Here’s what happened

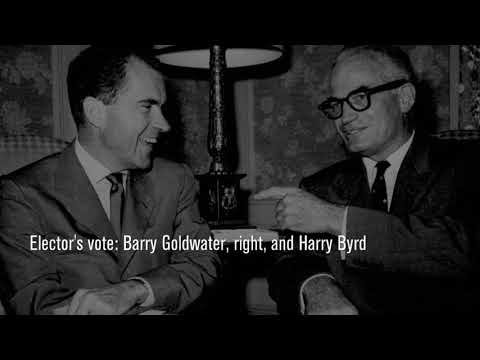

There have been a total of 157 faithless voters to date, according to FairVote.org, a nonprofit that advocates for national popular-vote elections for president.

It turned out to be a bipartisan effort.

In 1969, Republican President Richard Nixon supported a push in Congress to abolish the electoral college. So too did his rival in the presidential race a year earlier, Democrat Hubert Humphrey.

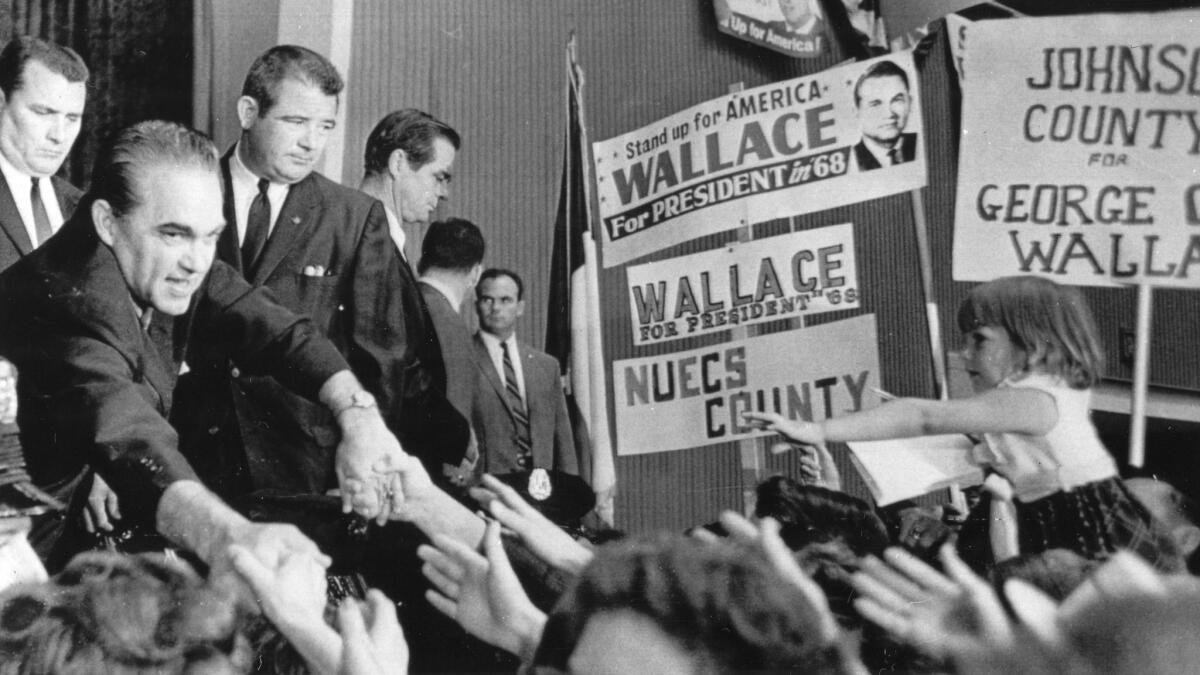

The reason both united in support: Former Alabama Gov. George Wallace.

Wallace — who had famously said, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever” — stoked racial animosity as the candidate of the American Independent Party. He won five Southern states and netted 46 electoral votes.

Here’s why an electoral college revolt is unlikely today »

Even before the 1968 election, there was fear that Wallace would win some electoral votes and possibly cause a tie between Nixon and Humphrey. Under the Constitution, the House of Representatives would then select the president and the Senate the vice president.

Although there had been previous proposals to abolish or alter the electoral college, Wallace’s strong showing finally gave the cause some momentum.

“I believe the events of 1968 constitute the clearest proof that priority must be accorded to electoral college reform,” Nixon said in February 1969.

I believe the events of 1968 constitute the clearest proof that priority must be accorded to electoral college reform.

— Richard Nixon, February 1969

To change the electoral college requires an amendment to the Constitution, which needs the support of two-thirds majority in the House and Senate, followed by ratification by three-fourths of the states.

“Congress and the states have let this situation continue for too long. The electoral reform issues raised in the recent election must be acted upon,” Humphrey wrote in an op-ed published in the Los Angeles Times in April 1969. “Direct election of the president would give each American citizen an equal vote — a fundamental principle of our democratic process.”

Although Nixon supported an amendment crafted by the American Bar Assn. that called for electing the president by popular vote, he also offered his own proposal to permit the election of a president by a plurality of 40% of the electoral vote, instead of an absolute majority. If no candidate received 40%, then a runoff would occur.

Ultimately, the plurality proposal Nixon supported did come to a vote on the floor of the House. It passed overwhelmingly in September 1969.

But hope for a change to the electoral college quickly faded.

Mark Weston, a historian of the electoral college and author of the “The Runner-Up Presidency,” said the amendment was filibustered and finally killed in the Senate by a group of Southern senators concerned that states with large populations would dominate elections.

“This really was essentially one of the last serious attempts to end the electoral college,” Weston said in a recent interview.

More recent attempts to scrap the electoral college have been motivated less by fears of a tie than the odd fact that a candidate can win the popular vote but still not take the White House. In the 19th century it happened three times — in 1824, 1876 and 1888.

Democrat Hillary Clinton won 2.8 million more votes than Republican Donald Trump nationally, but when the electors gather Monday to cast their ballots in state capitals, it’s virtually certain his victory will be made official.

In the days after Clinton’s loss last month, California’s outgoing Democratic Sen. Barbara Boxer — incensed by the outcome — introduced a proposal to abolish the electoral college system.

The time had come, she said, to get rid of the “outdated, undemocratic system that does not reflect our modern society.”

Clinton is the second presidential candidate in the last 16 years to win the popular vote, but lose the electoral college. Al Gore won the popular vote in 2000, but lost the electoral college vote after a recount gave George W. Bush the win in Florida and put him over the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency.

Since 1969, hundreds of efforts to end the electoral college have been floated, and the only other one to gain some traction came about a decade later.

Then-President Carter, citing the need to boost participation in elections, sent reform proposals to Congress, emphasizing the need for change.

“I do not recommend a constitutional amendment lightly,” Carter said in March 1977. “I think the amendment process must be reserved for an issue overriding the governmental significance. But the method by which we elect our president is such an issue.”

The amendment did not come to a vote on the Senate floor until two years later where it did not pass. That year, a group of liberal senators from Northern states, such as Delaware, Maryland and New York, opposed the effort, arguing, among other things, it would weaken the influence of African Americans and Jews in populous cities.

With a constitutional amendment so difficult to pass, other efforts are afoot to end the influence of the electoral college.

In 2006, John Koza, a computer scientist, penned a proposal creating the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact — an effort in which states agree to award all their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. So far, 10 states and the District of Columbia have signed up, including California, with its 55 electoral votes.

According to PolitiFact, the plan would not eliminate the electoral college, but it would dramatically alter its purpose and make it reflect the wishes of voters nationwide.

But supporters of the compact concede that even if more states eventually sign on, it’s likely to face court challenges.

Back in 2012 — before he was a candidate —Trump called the electoral college a “disaster.” Now, it appears, he’s a staunch defender.

“The electoral college is actually genius in that it brings all states, including the smaller ones, into play,” he tweeted last month, just days after the election.

Twitter: @kurtisalee

ALSO

Why our presidents are elected by a cabal of elites

The most important elevator in New York: Who’s riding to the top of Trump Tower?

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.