In northern Maine, collaboration brings better health

BANGOR, Maine — Sally Patterson reflected on her part in the healthcare system as she pointed her aging silver Subaru west on U.S. Highway 2 early one morning, headed for the tiny hamlet of Carmel.

“You’ve got to teach people how to look out for themselves,” Patterson said, whizzing past isolated houses, meadows and stands of pine. “It’s like the old biblical saying. Give a person a fish, you feed them for a day. Teach them how to fish, you feed them for life.”

Patterson is a nurse. She grew up learning to shoot a gun and to value community service. Her grandfather had a potato farm. Her great-grandfather drove Bangor’s first firetruck. She trained to work in surgical operating rooms.

PHOTOS: A personal touch to healthcare in Maine

Now she crisscrosses huge stretches of Maine’s North Woods region, leaving her house as early as 5 a.m. to visit some of the area’s sickest residents. She is part of a team of doctors, social workers and other nurses who work together to help patients manage their illnesses, live healthier lives and stay out of the hospital.

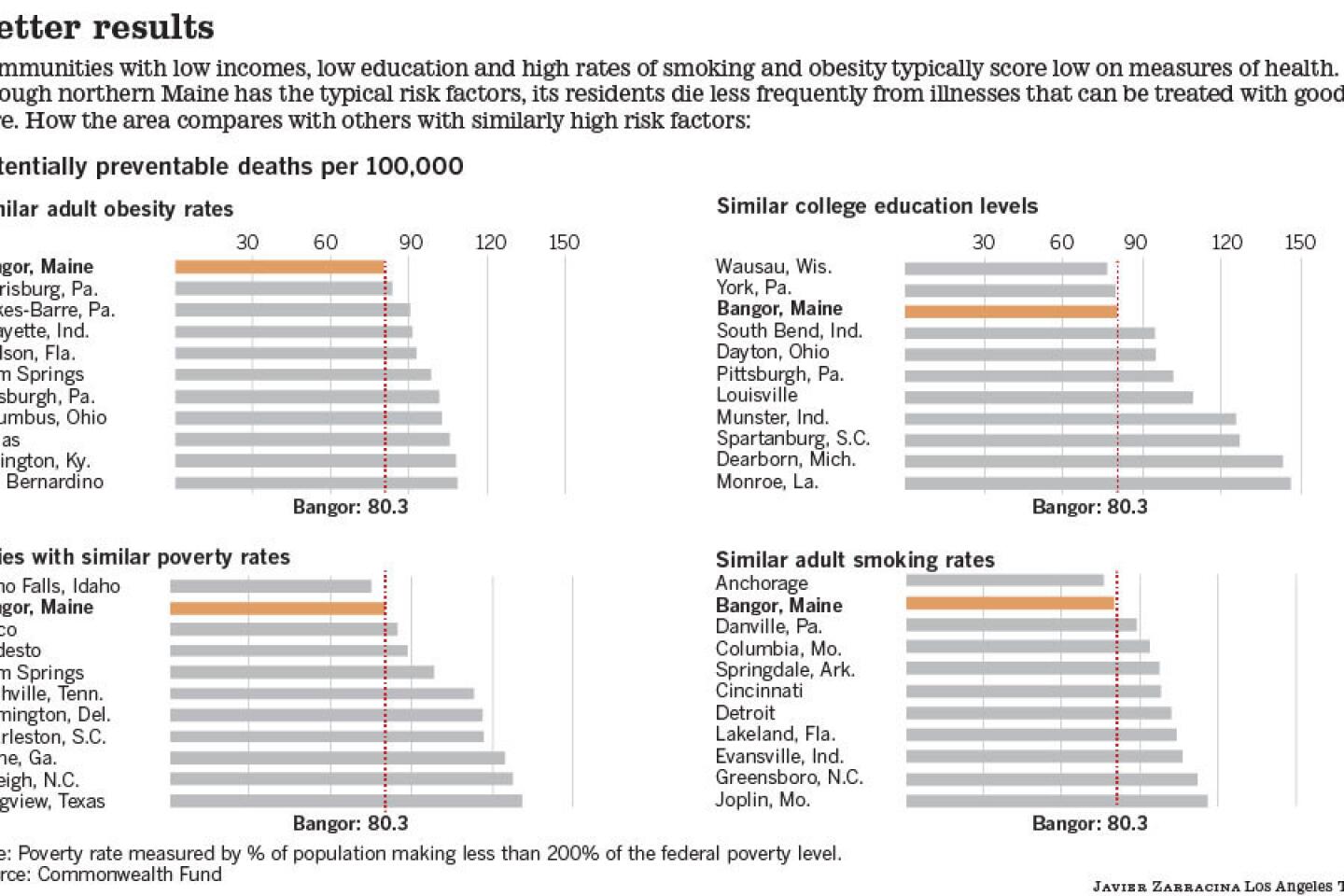

Many of the nation’s healthiest communities are wealthy and have large numbers of college-educated residents. But northern Maine is among a handful of telling exceptions, making it an important guidepost as the country searches for ways to improve health.

Once a booming hub of America’s lumber and fishing industries, the region now is among America’s poorest. Smoking is common. So, too, is obesity.

Yet northern Maine ranks high on national measures of health, according to a yearlong review of healthcare data from communities around the country that The Times conducted with help from public health researchers.

Residents of the region receive recommended screenings and medical care more often than other Americans. They suffer fewer complications in nursing homes and are less frequently prescribed risky medications. And they are nearly half as likely to die from preventable diseases as residents of other low-income areas, according to data from the Commonwealth Fund, a nonpartisan research foundation that studies healthcare systems.

Maine’s success owes much to the type of care that Patterson typifies — intensely personal, data-driven and highly coordinated. The approach grew out of a decades-long effort by local leaders that many experts consider a model for how to improve community health.

“I feel so lucky to live here,” said Gertrud Champe, 79, a retired college professor in Surrey, Maine, who has been getting intensive community-based care for years.

Champe suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a condition that often lands patients in the hospital, unable to breathe normally. But she has sought emergency care just twice in the last 10 years.

Today, she is able to work at home in an old farmhouse, translating medical texts. Every year, she visits her grandchildren around the country, and in the summer she spends hours in her garden among lupines and hydrangeas.

Like most of the healthiest states, Maine has invested in a strong safety net. It has expanded health coverage to thousands of poor residents who would have been denied insurance elsewhere. And it has a high number of primary care physicians, another factor associated with better health.

Maine also has something intangible: a strong spirit of collaboration and civic engagement.

That’s a feature of many of America’s healthiest places, from Massachusetts and upstate New York to parts of Michigan, Colorado and Arizona, the Times review indicates.

Physicians in Maine in the 1970s were among the first in the country to work together to examine why the care they were giving patients varied so widely from one community to another.

Guided by Dr. Jack Wennberg, founder of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in New Hampshire, they gathered at a lakeside lodge overlooking the White Mountains. Among the questions on the table: why surgeons in one town would remove a young woman’s womb at the first possible sign of cancer, while surgeons in neighboring towns did not.

Those inquiries helped spur decades of cooperation among Maine businesses, health insurance companies, hospitals and physicians. The 21-year-old Maine Health Management Coalition now publishes detailed score cards on physicians and hospitals, tracking more than 100 variables. The state’s largest employers, health systems and insurers take part. That, in turn, has helped change the way patients are treated.

In Bangor, the collaboration has yielded one of the nation’s most ambitious efforts to develop a more personal kind of care.

A small army of about 60 nurses and social workers calls and visits sick patients, often just talking with them about how to stay healthy. The goal is to keep people with chronic illnesses out of the hospital, improving their lives while saving money.

“We know that 99% of health decisions that patients make are not happening in the doctor’s office. They are happening at home,” said Jaime Boyington, who oversees what is known as a community care team for northern Maine’s dominant hospital system, EMHS. “We want to meet patients where they are.”

Insurance companies, the state and the federal Medicare program jointly pay for the program.

Some of Patterson’s patients are middle-class. Others live in public housing or rickety trailers in the woods, so infirm or depressed that they barely talk, much less regularly test their blood sugar.

One of her patients, an elderly man who lived alone on a fixed income, went to the emergency room 17 times, Patterson learned, simply because he was hungry.

Patterson wishes the healthcare system didn’t have to step in to help so many people, who in an earlier era might have relied on family and friends for more support. But she sees a simple value proposition in her work.

“If I can keep a guy from going to the hospital because we find out that he’s just after a sandwich, that’s worth my salary,” she said.

In Carmel, about 15 miles west of Bangor, Patterson checked in on Christine McDonald, a former nursing home assistant who was sharing an apartment in an old farmhouse with a roommate and her dog, Brandy, a Chihuahua-terrier mix.

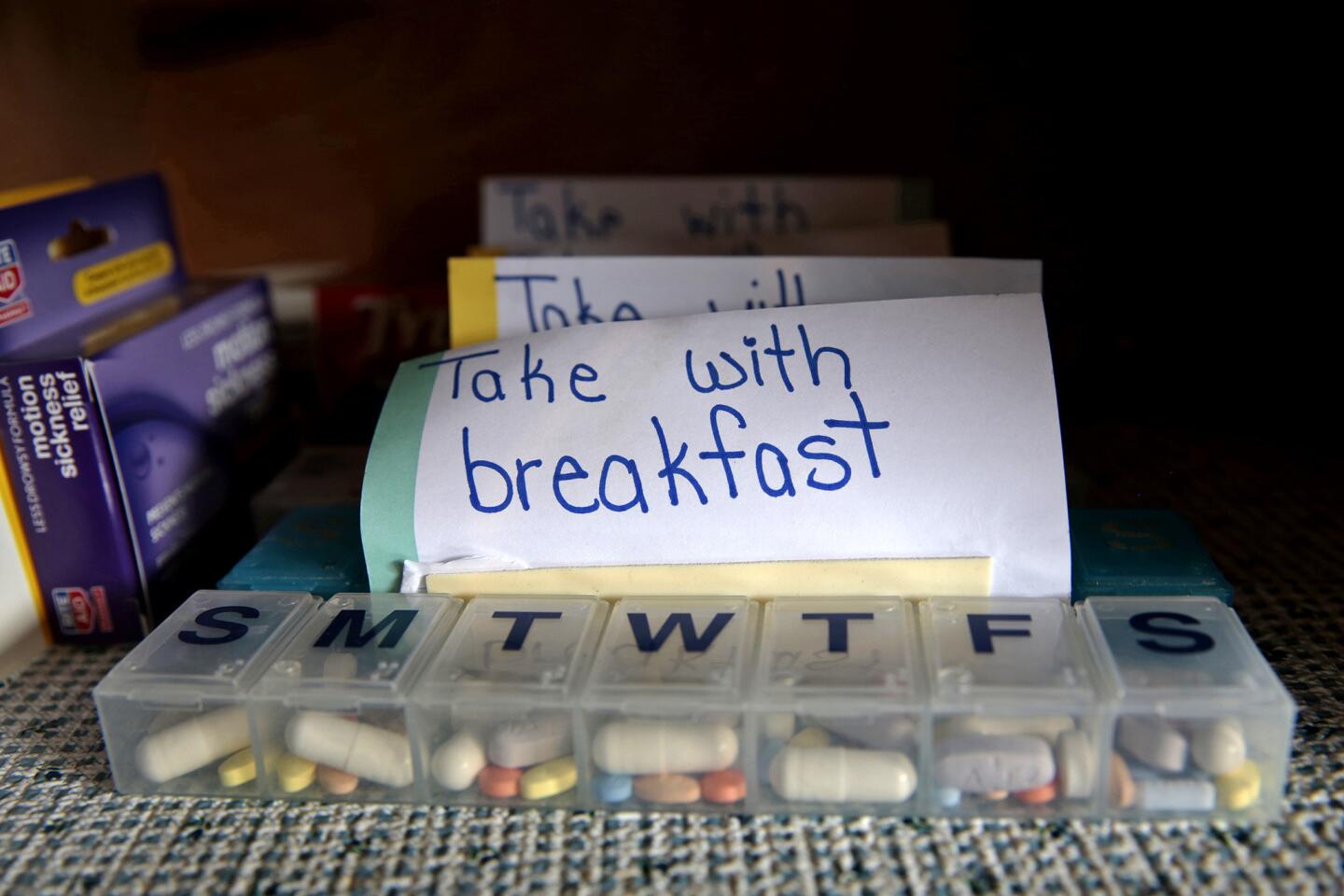

McDonald, 58, has diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe depression, exacerbated by the death of her son over the summer. She is on eight medications as well as insulin. Until recently, she was also a frequent visitor to the local hospital.

The last time Patterson visited, McDonald was still too shaken by her son’s death to talk about controlling her blood sugar. She hadn’t even opened many of her prescriptions.

On this morning, Patterson planned to help McDonald organize her pills in a new box Patterson had bought for her at Wal-Mart. But McDonald, after teasing Patterson for her sunny disposition — “It makes me sick,” she joked — was more receptive to a talk about her health.

Seated at a kitchen table decorated with a vase of plastic sunflowers, Patterson gently counseled McDonald about the importance of eating smaller meals and checking carbohydrates on food labels.

Picking up a banana from the kitchen counter, Patterson advised shopping for smaller ones, which have fewer carbs.

“And remember,” she added, “veggies are free.”

Patterson wanted McDonald to check her blood sugar daily, a process that requires pricking a finger, dabbing blood on a test strip and sliding the strip into a palm-sized monitor. But McDonald was hesitant.

“Well, let’s give this time,” Patterson said. “I’ll call you and remind you. You’ll know someone is interested.”

Patterson is philosophical about what she can accomplish. “If you ask for miracles, you’re both going to be disappointed,” she said. “People are going to make choices, and we can’t sit in judgment. We can just try to help them.”

Such personalized medical care is made possible by Maine’s advanced data systems. Still a rarity in some parts of the country, they can identify patients who need extra attention and allow doctors and nurses to track them in the region’s hospitals, cutting down on errors and over-testing.

In 2011, more than 80% of hospitalized patients in Maine were treated at medical centers able to exchange patient data with other providers, one of the highest rates in the nation and more than double that of some states, according to the Commonwealth Fund.

Bangor’s two largest hospital groups also have formed a partnership that gives each a financial stake in more than just filling hospital beds. The two systems, whose nurses and doctors now meet regularly to compare care, can benefit by keeping the region’s sickest patients healthy and thereby lowering costs.

“I don’t know that this would be possible in a duke-it-out, highly competitive market,” said Michelle Hood, chief executive of the EMHS hospital group, who worked previously in the much larger Atlanta and Birmingham, Ala., areas.

Community-based care hasn’t solved all of northern Maine’s health problems, particularly stubbornly high costs. Nor is it clear that similar partnerships would necessarily work as well in other areas.

Why Maine developed such a strong tradition of collaboration remains something of a mystery. “We used to joke that everyone gets along in northern New England because every hospital is separated by a mountain and the winters are long, so we’re happy to see someone,” said Wennberg, the Dartmouth doctor.

Many places with less collaborative healthcare systems also have low rates of participation in business, religious and other civic groups.

But around the country, some of those communities, including Dallas, Las Vegas and Memphis, Tenn., have started to bring medical, business and political leaders together to try to improve healthcare quality.

Maine’s numbers offer a promising example of what can happen when it works.

EMHS and its partners cut emergency room visits and hospitalizations among very sick patients by more than 40% in the first year. They also saw marked increases in the number of patients able to control their blood sugar and blood pressure.

After a few months of working with Patterson, McDonald lowered her hemoglobin A1c count — a measure of sugar in the bloodstream — from 9.4% to 7.2%, just above what is considered controlled diabetes.

“Sometimes I need a kick in the rear,” McDonald said. “But Sally’s got my back. ... I can talk to her. I like that.”

Support for this series came from the Assn. of Health Care Journalists’ Reporting Fellowships on Health Care Performance, funded by the Commonwealth Fund. David Radley at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Robert C. Wild and Dr. Ashish Jha at the Harvard School of Public Health assisted with data analysis.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.