Expiring tax credit sets off a scramble in Hollywood

WASHINGTON — Jennifer Tadlock doesn’t yet have all the talent lined up for the small-budget dramatic action feature she hopes to film next year, let alone a full crew. But she does have a tax break, and it’s expiring, which was enough to get her behind the camera last month.

Tadlock spent about $500 to hire a skeletal crew and nonunion talent to film just one scene near her home in Fresno. “We did the makeup ourselves,” she said.

The scene, involving teenagers plotting to harass an elderly woman, may never appear in the final cut. But by shooting this year, Tadlock hopes to lock in place the tax break that was key for investors who put up the $6 million she’ll need to shoot “Shades of Grace” for real next year.

“This is the biggest budget I have been able to secure, and that tax credit is why,” she said. “The risk of film these days is so high. There is no guarantee whatsoever your film will make back any money.… This guarantees investors they can write it off on their taxes. If it makes back money, that is just a bonus for them.”

The number and value of tax breaks for the film industry has soared in the last decade. States and the federal government together provide about $1.5 billion in tax benefits, according to estimates by the Tax Foundation and the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation.

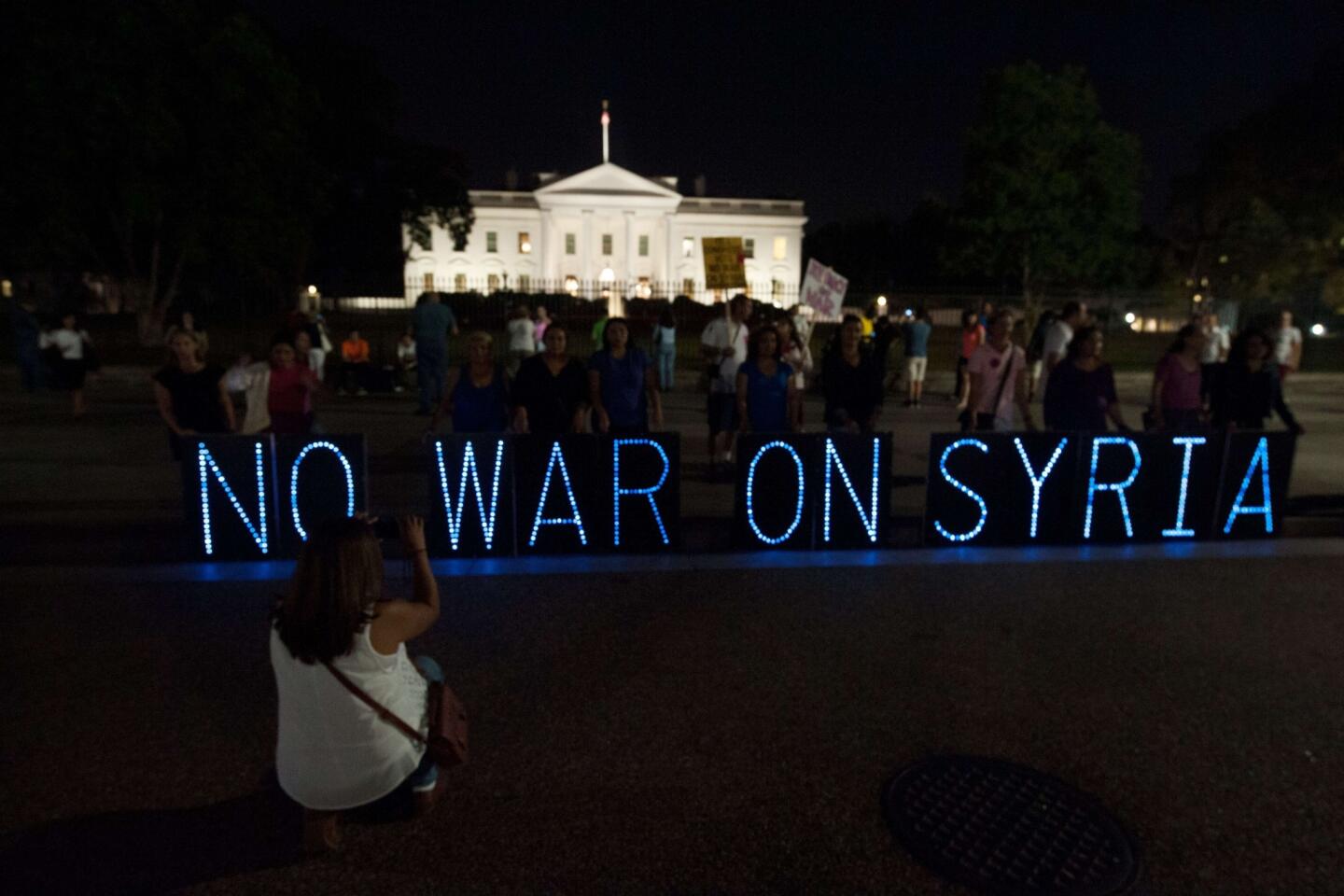

PHOTOS: 2013’s political moments

As a result, Hollywood films, often seen as a risky place to invest money, can be anything but chancy for wealthy investors who have learned that some of those tax breaks can be packaged to generate cash from even mediocre box office results.

This month’s scheduled expiration of just one of those breaks — a federal credit for production costs that the Treasury says will cost about $430 million over 2013 and 2014 — has set off a scramble. Some financial planners who package the deals have pushed producers like Tadlock to start shooting in hopes of keeping their projects eligible for the write-off even after it passes from the scene.

One attorney says he is trying to lock it in for his clients on 62 different projects.

Experts have argued for years about whether the generosity that cities, states and the federal government have shown Hollywood actually helps the wider economy. But there’s little argument that some tax incentives and subsidies have been a boon to a cottage industry of financial planners who have found ways to package them into windfalls for clients.

It helps if the movie is a hit. But that is not necessary.

“These things have become extremely lucrative,” said Carl Davis, senior analyst at the Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy, a Washington-based group that often critiques what its analysts see as loopholes in the tax code. “You are not going to find a lot of industries that have this kind of credit.”

Lawyers and financial planners who package such deals tout how profitable they can be.

“There is this impression created by those who don’t want people to get in an uproar about the subsidies and incentives that Hollywood is a dangerous and expensive place to be, and only dumb dentists from Miami invest in film,” said Troy Dyer, chief executive of Geneva Media Holdings, which arranges film financing deals for individuals with lots of income to shield. “That is not the case.

“The wisest of investors out there always make money in Hollywood, even on the crappiest of films,” he said.

Financiers often layer tax incentives with other maneuvers that allow for yet more breaks. Dyer’s firm markets a strategy that uses an unconventional payroll structure to exploit deductions allowed on crew insurance costs. He says it enables investors to double or triple the value of the credits a project receives.

The longtime financial planner and USC film school graduate says he helps the super-rich navigate these “loopholes” because “I believe in the arts.”

TIMELINE: The year in politics

“We don’t have a Medici family anymore,” Dyer said. “Where would we be without this funding? We are seeing the most important art that has been made in 50 or 60 years.”

Critics of the deals say they border on abusive.

“When you are getting all or nearly all your money back up front, that is not economic development,” said Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First, a liberal advocacy group in Washington. “When you create something that is this generous, you attract the gamers rather than the doers.”

The deals tend to involve independent film projects because many of the credits cap the amounts of money that can be used. The federal tax credit maxes out at $15 million per film, for example, which is much smaller than a typical blockbuster budget.

The details of the deals can often be mind-numbingly complex, but most follow the same general outline: The federal tax credit can be used to offset so-called passive income — money generated from such things as investments in real estate or limited liability corporations — which most taxpayers don’t have, but many wealthy people do.

Film producers, who often cannot use the credit themselves, particularly if their projects show losses, can form limited partnerships with wealthy investors who have passive income to shelter. The partnerships allow filmmakers to trade the credits for the investors’ cash.

Lucrative tax breaks have been at the root of a number of scandals, most recently in California, where the FBI is investigating whether state Sen. Ronald S. Calderon (D-Montebello) accepted bribes from an informant posing as a studio executive. Calderon has not been charged with any crime.

Investors need not break the law to make a mint.

Independent filmmakers keep close track of the tax rules, finding that a little knowledge of accounting minutiae can go far in drawing investors.

“In my pitch, I say to people, if you have federal tax liability, you are going to give that money to Uncle Sam regardless,” said Jason Pinardo, a Philadelphia filmmaker. “But if you give it to me, I am going to give you the chance to make some back.…

“You are no longer coming to them as just a passionate director with a script in your hand. You are talking to investors in terms they understand and can analyze it as a deal.”

PHOTOS: The year in national news

Among the most aggressive promoters of the credits is Chicago attorney Hal “Corky” Kessler, who is the one trying to lock in the expiring federal credit on 62 different projects.

Kessler was among those who lobbied Congress to create the incentive back in 2004 to keep film productions from shipping abroad.

“We were losing films to foreign countries,” he said. “‘Blues Brothers 2’ had just decided to film in Toronto instead of Chicago.”

Now, he says, he is doing work on a $15-million biopic that will recover its entire budget — and net investors a $1-million profit — “before the film ever gets distributed.”

Kessler would not reveal the plot or talent involved, but he claims that “presales” to distributors abroad coupled with very generous tax breaks in New York, where the film will be shot, and the federal tax credit, mean investors will make money even if the film fails at the box office.

Banking the federal incentive for later use is simple, he says: Filmmakers merely need to have a script, a budget, investor documents and a day’s worth of filming with dialogue. It doesn’t matter if the people filmed are actually in the cast of the movie.

Other attorneys say that is a risky strategy.

“I would not recommend to anybody that they shoot one day and put everything off until the middle of next year,” said Tom Selz, a New York attorney with extensive experience in film financing. “I don’t think that is the intent of the law.”

Still others say clients shouldn’t worry about missing the gravy train. The federal credit — or something just as lucrative — will be revived soon enough, they say. It has lapsed before, only to be carved back into the tax code amid pressure from the influential Hollywood lobbyists. Already, members of Congress have begun debating measures to restore some of the many business tax cuts that are set to expire by midnight Tuesday.

“Republicans like this because it is good for business, and Democrats are what most Hollywood industry insiders are,” Dyer said. “I think it will be renewed.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.