A city sends its troubles up in flames

In the span of 24 hours, Westin McDowell lost his job and his girlfriend. A day later, he stood glumly in the rain. His face, which he had painted to look like a mime’s, was beginning to run.

He was feeling downright dismal. But in a few hours, all the disappointment would go up in a puff of smoke.

McDowell, 26, had come here, to a park not far from Santa Fe’s main plaza, to take part in the city’s annual cathartic release: the burning of Zozobra.

For 85 years, locals have gathered annually to watch Zozobra -- a giant, grimacing marionette -- go up in flames. The effigy embodies all the gloom of the previous year, and when it is burned, those troubles are thought to vanish.

They call it the Santa Fe New Year.

“It’s kind of like an exorcism,” said McDowell, who has attended the event -- which draws a notoriously rowdy, often drunk crowd -- almost every year since he was 9. He said he hoped Thursday’s burning would leave him with a clean slate.

But there were still hours to go before the first sparks flew, so McDowell took a seat on the slick grass. On a big stage nearby, his nemesis swayed in the storm.

Fifty feet tall, with curly red hair and angry eyebrows, Zozobra wore a billowing white dress.

Zozobra was designed in 1924 by a local artist named Will Shuster, who said his inspiration came from the Holy Week celebrations of the Yaqui Indians of Mexico. In those ceremonies, an effigy of Judas was filled with firecrackers and burned.

Shuster’s creation had no religious significance. Rather, it was intended as an elaborate party trick for the city’s annual celebration, the Fiestas de Santa Fe. But the tradition carried on.

These days, the Kiwanis Club builds the effigy out of wood and cloth according to Shuster’s plans.

Zozobra is stuffed with things that people ask to be burned: paid-off mortgage papers, shredded copies of police reports, wedding dresses, straitjackets.

“People want to burn their boss, their job, their cancer, their broken relationships,” said Ray Valdez, who has been in charge of building Zozobra for the last 20 years. “We’ll take anything except glass and explosives.”

Zozobra is also filled with slips of paper, scribbled with people’s personal troubles.

At the “gloom booth,” where people were invited to write down their problems to be burned, Sadie Rizika, 5, and her sister, Hannah, 7, picked up pens.

“I wrote for all my bad dreams to go away,” Sadie said. Her father, Steve, 42, decided to write down the names of the negative people in his life. “They’re all going to burn!” he said, laughing.

Another pair of sisters, Patty Cervantes, 54, and Ida Cordova, 52, wrote about two deaths that recently touched their family.

“We just want this year to be over,” Cordova said. “We felt it was necessary to come to remove all of this sadness. We’ve been crying and hugging and trying to let it go.”

They also reminisced about the last time they attended Zozobra together, back in the 1970s.

“Back then it was more of a fiesta,” Cervantes said. “We camped in the plaza and didn’t have to pay. There were bottles of tequila and we’d just be passing them.”

Today, entry to the festival costs $10 and alcohol is not allowed, although many people sneak it in.

Robert “Otter” Allen, 28, came from Albuquerque, 50 miles away, where he works as a massage therapist.

“There’s a lack of ritual in today’s society,” Allen said. “But it’s so important. The soul cannot migrate unless it goes through a transformation.”

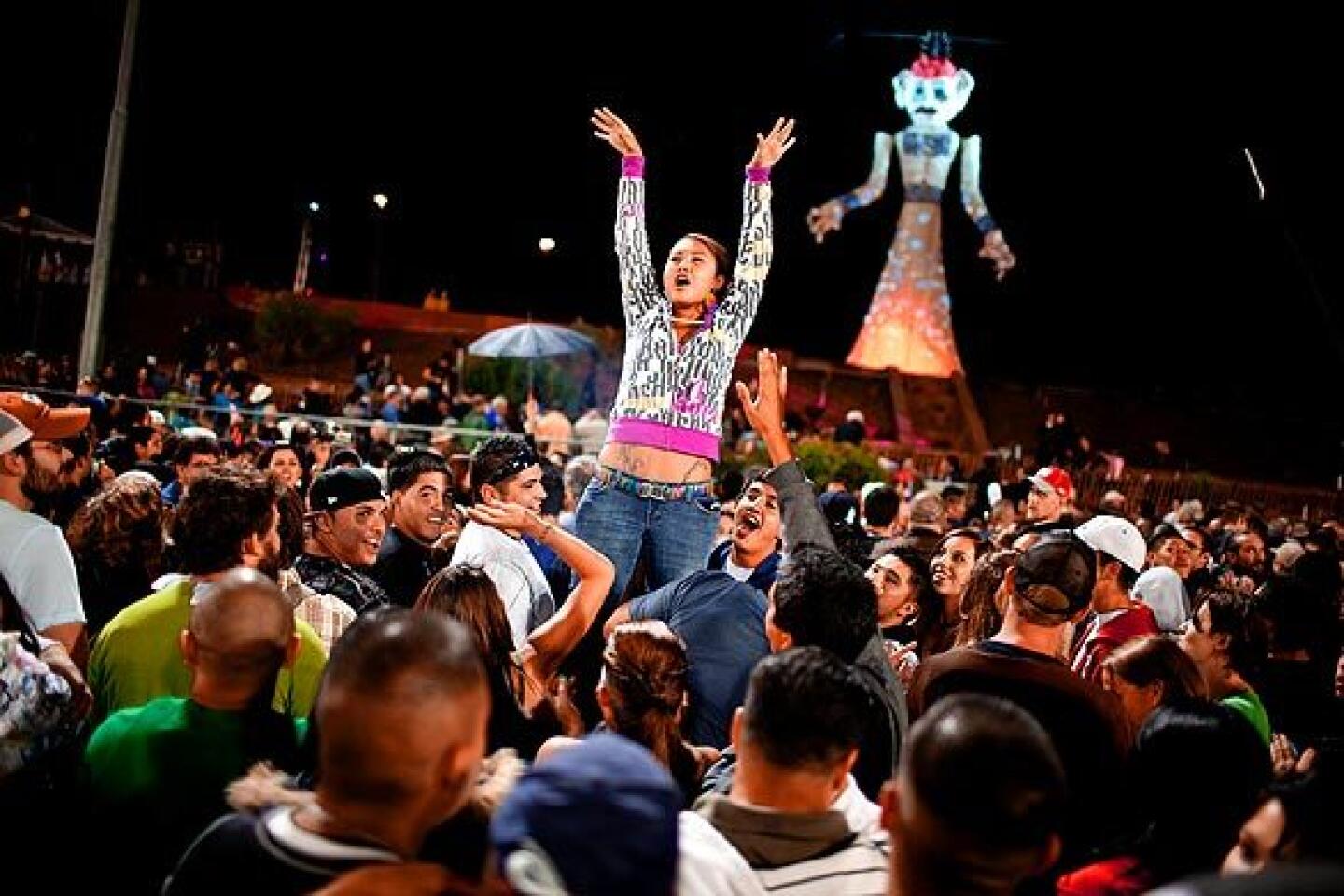

Suddenly, the floodlights that had illuminated the field went dark. A roar of approval rose from the crowd of more than 20,000, and people began to chant: “Burn him! Burn him!”

McDowell -- unemployed, alone, his face paint smeared -- stood near the front of the tightly packed audience.

A troupe of “gloomies” -- children cloaked in white bed sheets -- flooded the stage in front of Zozobra and whirled around. Dancers in black body paint twirled flaming batons. The “Gloom Goddess,” a young woman dressed in shimmery white, danced with a giant torch.

Fireworks erupted over the frenzied crowd. And Zozobra came to life.

His eyes, shining blue lights, blinked madly. His arms, controlled by ropes, groped angrily. A low growl was amplified over giant speakers.

An arrow of fire shot from the ground pierced Zozobra in his neck. He groaned. A ball of fire erupted from his mouth and began creeping up his face. Soon his towering head was swallowed up by flames, and then it collapsed onto his body.

On the stage in front of McDowell, a pile of rubble burned like the remains of a great car wreck. Around him, people whistled and howled and screamed.

McDowell just stood there, hands in his pockets, and gazed up at the smoky sky.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.